![]()

PART 1 • Fault Lines

![]()

1 • COUNTING SHEEP

It was a terrible sight where the slaughtering took place…. Near what is now the Trading Post was a ditch where sheep intestines were dumped, and these were scattered all over. The womenfolks were crying, mourning over such a tragic scene.” Nearly four decades had passed since the 1930s, but still Howard Gorman could not erase the mental images of the calamitous period of Diné history known simply as “livestock reduction.” A handsome, educated man and eloquent orator whose short dark hair and suits suggested a business executive, Gorman served as vice chairman of the Navajo Tribal Council from 1938 until 1942 and represented Ganado on the council for another three decades. More than most Diné, he had gained a broad perspective of the New Deal conservation program, for he often acted as a liaison between the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Diné during that era, in part as assistant and interpreter for General Superintendent E. Reeseman Fryer, with whom he traveled across the reservation to explain the government's policies. Still, he recalled the era with anger and profound sadness. The butchery he witnessed at the Hubbell Trading Post near his home outside Ganado seared his memory.1

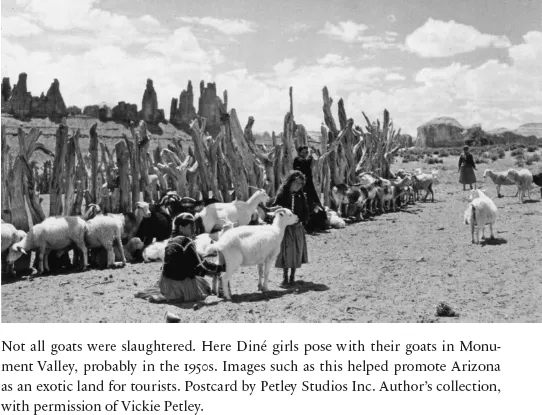

Billy Bryant bitterly remembered that time, too. At first, stock reduction had largely escaped his notice. The BIA launched the program in 1933, but it did not affect Bryant right away. He and his wife, who lived near the western boundary of the Hopi Reservation, went about their daily lives as they always had, herding their livestock, eating goat meat and mutton, and occasionally butchering a fat lamb for a feast with their relatives and friends. Then one day in October or November 1934, all that changed. Perhaps on that day Bryant saw a cloud of dust on the horizon announcing a visitor, who arrived to round up his wife's goats.2 The government at first shipped herds of confiscated goats to various slaughterhouses, where the meat was canned for distribution to Navajo schools, but canneries quickly reached capacity, among other problems. So federal agents simply killed the goats while their owners looked on.3

Bryant would never forgive the cruelty and waste he witnessed on that terrible day in 1934, nor the powerlessness and indignity he felt at the hands of federal authorities. “Our goats … were put into a large corral where they were all shot down. Then the government men piled the corpses in a big heap, poured oil or gasoline on them and set fire to them. This happened just below Coal Mine Mesa at a place called Covered Spring. One still can see the white bones piled there…. Not only the goats, but the sheep, too, were slaughtered right before the owners. Those men took our meat off our tables and left us hungry and heartbroken.”4

Sarah Begay recalled those nightmarish days, too. Out of the blue, some men rode up to her place in Narrow Canyon, near Kayenta, and killed her goats. “They did it right before my eyes. I was there with my husband. They took so many.” Some were actually her mother's, and some belonged to her older sister. “‘That is enough; it is enough,’ I tried to say.” But the men ignored her; they herded the goats to a place behind a bluff, where they beat them with clubs and shot them. “Some of the women were really crying,” she remembered. “That is why we don't sleep well sometimes. All we think about is that.”5

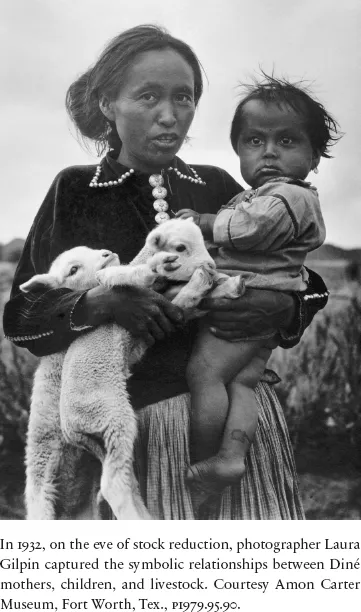

Like Begay and Bryant, hundreds of Diné women and men watched helplessly while federal agents destroyed their means of subsistence, their years of labor invested in building herds, their legacy to their children. But those scenes proved singularly traumatic for deeper, spiritual reasons, too. As Howard Gorman explained, “Some people consider livestock as sacred because it is life's necessity. They think of livestock as their mother.”6

Livestock had long nurtured the Diné, and as their animals lay dying on the parched, naked ground, the Diné felt an overpowering sense of foreboding. Horses and sheep had been a gift, a life-sustaining blessing from the Diyin Dine’é, the spirits who manifested themselves as wind, thunder, rain, and sun.

7 The ruthless destruction of that gift was savage

and wasteful, but more than that, it showed profound disrespect for the Diyin Dine’é. Many felt, too, that such an act would disrupt the environmental balance articulated in the spiritual concept of hózh

. It would bring disorder. There would be no more rain and the earth would wither.

8 And so, as soil conservationists introduced one plan after another to slash Navajo herds, the Diné became increasingly defiant. At stake, after all, was the land itself. Today, looking back on the 1930s, many Diné view the shriveled plants and the desiccated and often denuded landscape of Diné Bikéyah as a logical consequence of the federal stock reduction program.

And they are right.

One needn't even accept Diné causality to conclude that stock reduction laid waste the land. The government's wanton slaughter of livestock, without regard to how culturally and economically important sheep, goats, and horses were to Diné, hindered efforts to encourage Diné to manage their herds with an eye toward long-term stewardship of the range. As Howard Gorman observed, “The cruel way our stock was handled is something that should never have happened. The result has left the condition of the land and stock the way it is today. What John Collier did in stock reduction is something the people will never forget. They still consider him a No. 1 enemy of the Navajo people.”9

John Collier never intended to become the enemy of the Navajos. First as a leading advocate for the Puebloan people of New Mexico and then as executive secretary of the American Indian Defense Association, he had championed the right of native people to self-determination, particularly their right to practice cultural traditions like pastoralism. He fought for religious freedom at Zuni and Taos pueblos and helped defeat efforts to alienate lands from all the New Mexico pueblos. While his battles on behalf of Puebloan people are better known, Collier also fought for Navajo land rights during the 1920s. Since 1871, when Congress abolished the practice of negotiating treaties with Indian tribes, presidents had created new reservations or expanded existing ones by executive order, and the legal title of those lands remained precarious, subject to congressional challenge. Collier lobbied for Navajo rights to royalties from oil and gas leases on their executive-order reservation lands and, in the process, helped confirm tribal title to them.10

Collier's commitment to native peoples grew out of his work as a social reformer. Born into a prominent family in Atlanta, Georgia, Collier knew privilege and tragedy. His mother died when he was only thirteen, and his father, a Progressive community leader, perished from a gunshot wound—perhaps an accident, perhaps suicide—less than three years later. Reeling from his father's death, Collier hiked through the southern Appalachians, where he found solace in nature and, as if by revelation, a calling to a life of social reform. At Columbia University, he read widely in philosophy, biology, sociology, and psychology, then traveled to Europe, where he met his first wife, Lucy Wood (whom he would divorce thirty-seven years later to marry the anthropologist Laura Thompson), and became captivated by the emerging collectivist movements.

Like many of his generation, Collier's misgivings about modernity—its industrialism, rationalism, and materialism and its gender and class hierarchies—drew him to other cultures in search of a more authentic existence. Upon returning to New York, he joined the staff of the People's Institute, where he developed youth programs to preserve immigrant traditions and foster a sense of multicultural community. At the same time, he became a regular visitor at Mabel Dodge's famous Greenwich Village salon, a forum for bohemian artists, socialists, feminists, and radical intellectuals. It was Dodge who introduced Collier to the world of native peoples, when she invited him and his family to her new home near Taos Pueblo. In the pueblos, he felt he finally found the cultural persistence and communalism he had been seeking among New York's immigrants. He subsequently moved to Taos to work for the General Federation of Women's Clubs in its mission to investigate and reform federal Indian policy.

Throughout the 1920s, Collier challenged the policy of cultural assimilation that had governed Indian affairs since the late nineteenth century. That policy had defined Indian tribes as “domestic dependent nations,” whose relationship to the federal government, wrote Chief Justice John Marshall, was like “that of a ward to his guardian.”11 Guided by that paternalistic notion, the BIA endeavored in the decades after the Civil War to remake Indians into patriarchal families of Christian farmers, first on segregated reservations and later on individually allotted farms. Although this plan had grown out of a humanitarian reform movement to put an end to genocidal Indian wars, in hindsight the program was racist, even cruel. Many children, who became the focus of assimilation, were wrenched from their families and sent to often-distant boarding schools, where they were indoctrinated with Christianity; trained in agriculture, homemaking, and the mechanical arts; instructed in the English language; and punished for speaking their native tongue. Back home, their parents faced persecution for engaging in traditional ceremonial dances and other religious practices. In essence, advocates of assimilation pledged to eliminate what they called the “Indian Problem” through cultural genocide. As Senator John Logan of Illinois tellingly articulated it, the goal was to make them “as white men.”12

The mishandling of tribal resources accompanied the assimilation program. Under the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887, the BIA broke up reservations into individual farms throughout much of the United States, with relatively little effort to prevent the loss of those allotted lands to predacious Euro-American settlers. Oftentimes, too, Indian agents misappropriated tribal funds earned through oil leases and land and timber sales instead of investing in the equipment and infrastructure that might have fostered economic self-sufficiency. Pervasive poverty thus plagued Indian Country.13

For the Diné, the worst had come in the years between 1863 and 1868 with their incarceration at the place they named Hwéeldi. Better known among Euro-Americans as the Bosque Redondo, Hwéeldi was established to punish Navajos for raiding New Mexican stockmen and to secure the western frontier during the Civil War. The nightmare began with a series of forced marches over hundreds of miles to Fort Sumner, which guarded a flat, almost treeless plain along the Pecos River in east-central New Mexico. The Long Walk, as it came to be called, was miserable for everyone, but all the more so for pregnant women, the sick, the elderly, and the very young. At Hwéeldi, the Diné, who were farmers as well as shepherds, found it impossible to cultivate the alkaline soil and combat the swarms of insects that consumed what little corn they managed to grow. Government rations were scanty and often spoiled, and the water was undrinkable. Many Diné died of starvation, exposure, disease, and heartache. Finally, in 1868, the Diné signed a treaty that allowed them to return to their homeland and take up stockraising and farming again. But they would never forget the trauma of those years, nor the power of the United States government.14

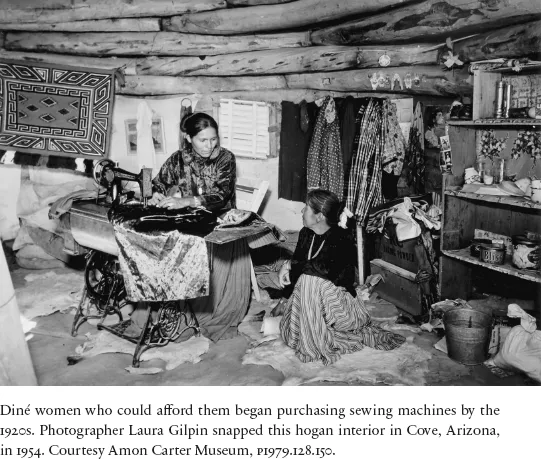

In the decades after their return from Hwéeldi, the Diné remained remarkably independent of the government, with which most had little contact. To be sure, they were not totally unaffected. Until the 1930s, the BIA divided Navajo Country into six jurisdictions, each with its own federal agent. Some of these men were conscientious custodians who guarded Navajos’ interests, others were neglectful. All of them promoted the rapid development of livestock herds for economic self-sufficiency and assimilation into the larger capitalist society. By the end of the nineteenth century, Diné women wove blankets for a commercial market, and families bartered wool, pelts, and blankets for goods at trading posts. Nonetheless most Diné continued to live in traditional matrilocal communities of extended families, maintained age-old spiritual practices, and evaded efforts to educate their children or adopt market-oriented livestock husbandry, with little interference from the government. The far-flung pattern of rural residences across a rugged, largely roadless terrain made it impossible for agents to keep a tight rein.

Collier was particularly mindful of the Navajos’ independence when in 1933 President Franklin Delano Roosevelt appointed him commissioner of Indian affairs and endorsed his agenda to replace paternalistic control and assimilationist goals with self-rule and cultural revival. Collier believed that native communities somehow captured a purer, more essential way of life. Native cultures, particularly that of the Navajos, he thought, retained an admirable authenticity. In the 1920s, he had written that the Navajos were paragons of self-sufficiency and cultural integrity, a beacon for the larger society to follow. They had “preserved intact their religion, their ancient morality, their social forms and their appreciation of beauty.” Despite major changes to their economy since their return from the Bosque Redondo, “their tribal, family and rich inner life remains unaltered,” he acclaimed, “an island of aboriginal culture in the monotonous sea of machine civilization.”15

Collier might well have become a hero to the Diné, for he waged a revolution in Indian policy during his administration. With his landmark legislation, the Indian Reorganization Act, he promoted a measure of self-government and economic development, restored to many tribes some of the reservation lands that had been parceled out under the Dawes Act, supplanted boarding schools with community day schools, fostered religious freedom, and laid the institutional groundwork for modern native nationalism.16 He was no less a paternalist than his predecessors, but he took his custodial role seriously. Upon his appointment as commissioner, he announced: “I strongly believe that the responsibility of the United States, as guardian of the Indians, ought to be continued…. But the paramount responsibility is with the Indians themselves. Within the limits of a protecting guardianship, the power should be theirs. The race to be run is their race.”17 Collier would repeatedly assert that his mission was to unleash Indians so that they could realize their full potential. “The essence of the new Indian policy,” he wrote, “is to restore the Indians to mental, physical, social, and economic health; and to guide them, in friendly fashion, toward liberating their rich and abundant energies for their own salvation and for their own unique contribution to the civilization of America.”18 With the Indian Reorganization Act as the centerpiece of his new program for Indian self-government and economic development, Collier sought to stage a dramatic reversal of a century of federal policy. In so doing, he cast Navajos in a central role. Navajos, in his view, were model Indians on which to drape his New Deal program.

But first, he felt compelled to stave off a looming environmental disaster: accelerated erosion brought on by decades of overgrazing. Each summer, violent rains washed eroded soils through a network of arroyos, the waters gushing into the San Juan and Little Colorado rivers then dumping their silt load into the turbulent Colorado River. Left unchecked, alluvium from the Nav...