![]()

CHAPTER 1

Colonial Beginnings

Reformation and European Expansion

Medieval Europe dreamed of Christendom—one civilization united by one faith. This ideal of Christendom was shattered in the sixteenth century when Protestant reformers broke with papal authority in Rome. Europe became a patchwork in which each territory was its own little Christendom with its ruler determining the religion of the people. Meanwhile, several European powers laid claim to huge tracts of land across the Atlantic Ocean. These territories were named New Spain, New France, New Netherlands, New Sweden, and New England.

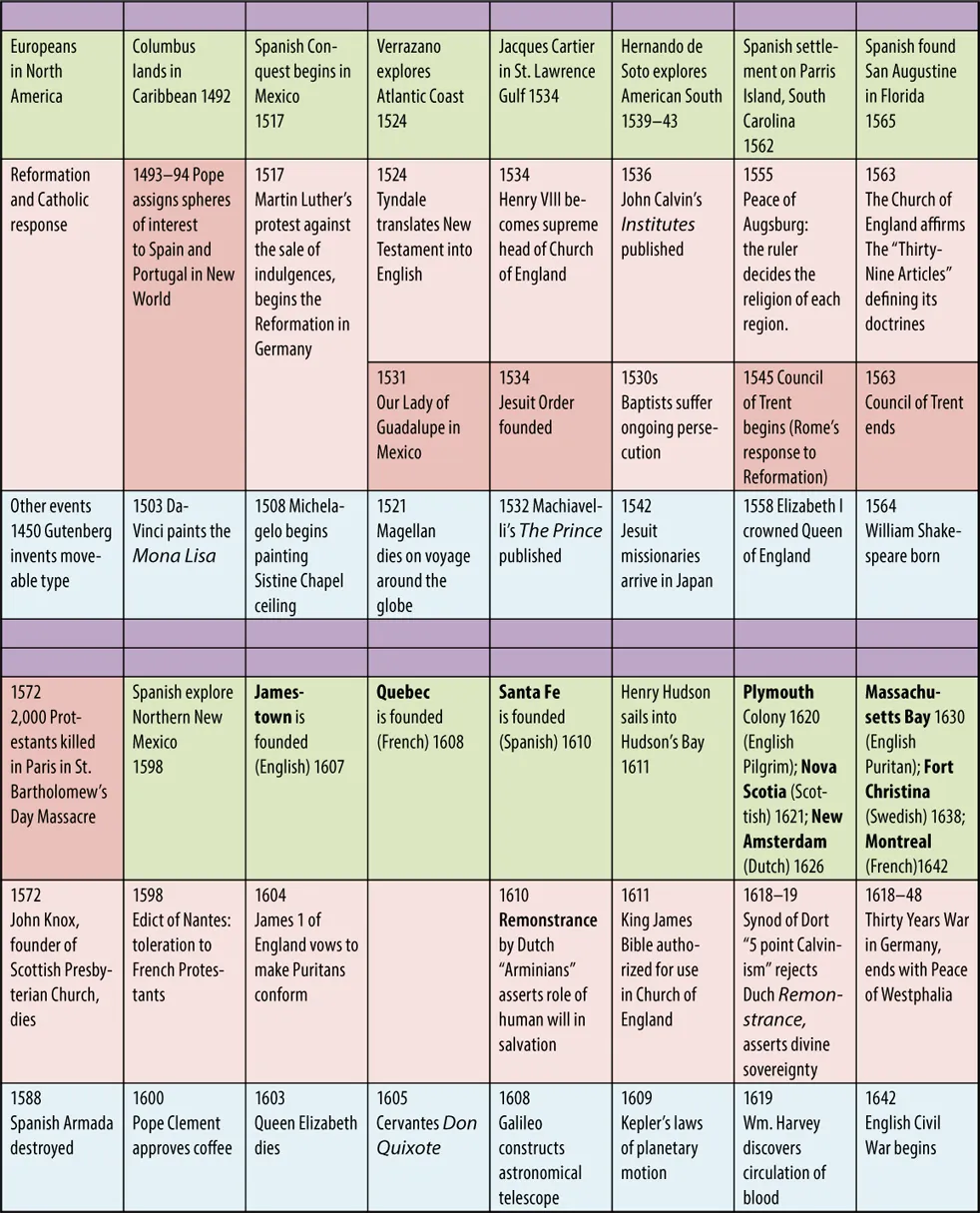

Thus, two great dramas overlap in time: the Reformation and European expansion in the Americas. For example, Luther began the Reformation in 1517, at about the same time Córdoba explored the Yucatan peninsula. William Tyndale prepared his English translation of the New Testament in 1524, the year that Verrazano probed the Atlantic coastline. In France, a young lawyer named John Calvin embraced the Reformation in 1534, the year Jacques Cartier first sailed into the St. Lawrence Gulf. By the close of the Reformation era in 1648, European settlements in North America included Jamestown, Quebec, Santa Fe, Boston, and New Amsterdam (New York).

The Reformation affected European exploration and settlement of America. Not only did Protestant and Catholic nations compete for territory; they also brought to America several assumptions and strategies forged in the Reformation. These concepts were the basis for colonial Christianity, at least in the early stages. One such concept was territorialism.

Fig. 1.1 Territorial Claims over North America. Europeans attempted to apply the principle of territorialism (the ruler decides the religion of each region) to their spheres of influence in the New World as well as in Europe. The policy, though impossible to enforce, shaped the cultures of these regions for generations. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Territorialism was a strategy for dealing with the religious diff erences set loose by the Protestant Reformation. By 1648, religious and political wars had failed to establish either Catholicism or any type of Protestantism as Europe’s sole faith. War could not settle the matter. The slogan cuius regio, eius religio (“whose the region, his the religion”) expressed the strategy by means of which rulers tried to assert religious unity within their own realms. The ruler decided the religion.

European rulers expected their religious authority to extend to their American territories as well. To this day, the religious footprint of territorialism can still be seen in French-Catholic Canada, in the heritage of Spanish Catholicism in Mexico and the Southwest, and in the Anglo-Protestantism in much of the United States.

Another theme from the Reformation era was freedom of conscience to “obey God rather than men” (Acts 5:29). Here the individual is accountable to God alone in matters of faith. No human authority, not even a king or a bishop, has the right to gainsay God’s claim on an individual. And if this does happen, the individual is bound by conscience to resist. These two views of religious authority—territorialism and individual conscience—clashed repeatedly in colonial America until religious freedom at last became the norm.

American Lutherans have sometimes been tempted to draw a straight line between Martin Luther and the rise of religious freedom in America. A crooked line would be better for two reasons. First, Calvinism (not Lutheranism) was the dominant influence in American Protestantism for generations. Second, Luther did not think that one person’s beliefs were as good as any other person’s, nor did he say that individuals should simply believe whatever appeals to them. Luther (and other reformers) did say that when human authority conflicts with the Word of God, then God must be obeyed. Martin Luther criticized the church of his day not because he was a free spirit but because his conscience was “captive to the Word of God.” This and similar appeals to the Word of God continued to inspire dissent against religious territorialism in the colonies. With the Enlightenment came new forms of dissent. For those influenced by the Enlightenment, the conscience of the individual (rather than the Word of God) became the final court of appeal. In the story of Christianity in colonial America, territorial religion (in which the ruler sets religious policy) clashed with appeals to a higher authority—whether Scripture, conscience, or reason. These conflicts began in Europe during the Reformation and took on a life of their own in America.

Fig. 1.2 Reformation, New World Settlement, and Cultural Events

Native American Religions

The Reformation was still in the future when Columbus landed on the island he called San Salvador in 1492. There he saw no temples or robed priests, heard no prayers or liturgies. Columbus wrote that “Los indios … will easily be made Christians, for they appear to me to have no religion.”1 Columbus was an explorer, not a sociologist of religion. Even if he had been able to see and describe the religion of the Taino people, this would have been one among hundreds of religions in North America at the time of European contact.

There is no separate word for “religion” in many Native American languages. Instead, there is a “whole complex of beliefs and actions that give meaning” to everyday life.2 In Native American religion, spiritual forces helped people to carry out the central tasks of hunting, courtship, and warfare. Healing was especially important; shamans or holy people would use spiritual powers to remove the evils that caused pain and sickness, or to restore the good things that had been stolen by bad spirits.

Native American beliefs passed by word of mouth to each new generation. Stories told the people who they were in relation to the land and to other tribes and marked the rites of passage in life. In contrast to European Christians with their written scriptures and creeds, Native cultures relied on oral tradition.

Land was central to Native American religions. Land was not “private property” or “real estate.” It was sacred, the mother of all living things. Land was revered not for its monetary value but for its beauty, for its abundance of game and fish, and as a reminder of great events and spirits of ancestors. But even before the Europeans came, native peoples could be displaced from their ancestral lands by tribal warfare or by changing patterns of climate, hunting, and trade. When the Europeans came with their relentless appetite for land, the conflicts had religious dimensions, not least because land was sacred to Native peoples.

From colonial times until well into the twentieth century, missionaries to Native American peoples seldom differentiated the Christian gospel from their own cultures. A common assumption was that Native converts must forsake all tribal ways in order to become Christian. Even so, missionaries tended to treat Native peoples more humanely than did most of their fellow Europeans. Missionaries were more likely to see Native people as human beings, with souls to be saved, than to see them as enemies to be killed or obstacles to be removed from the path to progress. Many missionaries learned the languages and customs of Native peoples. A few missionaries lived with Indian peoples and adapted to tribal ways. Missionaries sometimes became advocates for Native peoples, condemning white encroachment on Indian land or trying to stop the alcohol trade that all too soon blighted Native cultures. Some missionaries paid the ultimate price of martyrdom in their attempts to bring Christianity to Native peoples.

Even the best-intentioned Europeans, however, could unwittingly carry smallpox, measles, and other diseases against which tribal peoples had no immunities. The death toll from European diseases may never be fully known, but estimates run to the tens of millions of Native people. Hardest hit were those peoples who lived in larger, more settled communities. For example, the Pueblos of New Mexico had roughly forty-eight thousand people in the sixteenth century. But by 1800 they were down to about eight thousand people.3 The loss of entire peoples, with their cultures and religions, can scarcely be measured.

Box 1.1: Our Lady of Guadalupe

On December 9, 1531, a Native American man named Juan Diego saw a vision of a of the Virgin Mary. She appeared to him on Tepeyak hill near Mexico City, and spoke to him in Nahuatl, his native language. She told him to build a church for her on that very place. Juan Diego went to nearby Mexico City and reported his vision to the Spanish bishop. The bishop sent him back to Tepeyak hill to ask the lady for a sign that she was indeed the Virgin Mary. Once more she appeared and told Juan Diego to gather roses in his cloak (although the hillside was barren and it was not the season for roses to bloom). However, Juan Diego searched the hillside and found beautiful roses (the kind that grow in the Castilian region in Spain). He gathered the blooms in his cloak and carried them to the bishop. And when Juan Diego let the roses tumble gently from his cloak, an image of the Virgin Mary remained miraculously imprinted on that garment. On Tepeyak hill a shrine was built, replaced over time by more elaborate churches.

Today pilgrims flock to the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe, where the image said to be the original on Juan Diego’s cloak is on display as a sacred relic. Millions visit this site every year, making it second only to Rome as a pilgrimage destination for Catholic Christians.

Fig. 1.3 Our Lady of Guadalupe, also known as the Virgin of Guadalupe, sixteenth century. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The image of our Lady of Guadalupe has great significance in Latin America. It was used on a banner in the Mexican War for independence from Spain (1810–1821) and became a symbol of Latino self-determination. Most of all it is an icon of devotion for Hispanics in North and South America. The Virgin Mary’s reported appearance to a Native American shortly after the Spanish conquest of Mexico is taken by many as a sign of God’s love for the poor and oppressed.

Some scholars challenge the historicity of the story. What is certain is that millions of people identify with our Lady of Guadalupe as a symbol of religious faith and cultural identity.

Catholic Missions in North America: Spain and France

The first Catholic missionaries to America arrived with Columbus’s second voyage in 1493, making their landing on the island of Hispaniola (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic). By the early 1500s, Spanish priests were active in Mexico, a large area whose northern lands later became part of the United States. This area, in turn, was part of a much larger Spanish empire extending through Central and much of South America.

Conquistadors (explorer-soldiers) advanced Spain’s empire by crushing Native resistance. Spanish settlers carried on trade and provided a permanent European presence, while missionaries converted the Native peoples to Catholicism and taught them European ways. Thus, “conquest, settlement and evangelization” brought about a new rule whose purpose “was to create Christian peoples out of those regarded by their conquerors as members of barbarous and pagan races.”4 The Spaniards had many internal conflicts between military, church, and trading interests; but there was general agreement that Native peoples who became Christian had to abandon tribal ways.

Spain could send very few European settlers to the far edges of its empire. It therefore sought to keep other European powers away by converting Native peoples and making them into loyal Spanish subjects and devout Catholics. Consequently, Spain established missions in Florida and along the northern rim of the Gulf of Mexico. In New Mexico, twenty-five missions were established by 1630. Another stage of mission planting was led by the Jesuit missionary Eusebio Kino (1645–1711), who was active in what we now know as the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico. Later on, Spain built a string of missions in California between San Diego and San Francisco, with the dual purpose of converting Indians and securing Spain’s claims against Russian and English interests along the Pacific coast. The Franciscan missionary Junipero Serra (1713–1784) led in creating these California missions. Serra gathered Native peoples into the missions, where they were taught Christianity, European customs, and agriculture. He is said to have baptized six thousand persons and confirmed five thousand. In keeping with attitudes of his day, “Serra held that missionaries could and should treat their converts like small children. He instructed that baptized Indians who attempted to leave the missions should be forcibly returned, and he believed that corporal punishment—including the whip and the stocks—also had a place.”5

Spanish missions often resembled medieval European villages. Inside the protective walls lay the church, school, and hospital as well as a dormitory and work areas for various trades. Outside the walls, the people ...