GETTING PREPPED:

- Do only fringe religious groups produce apocalypses?

- Can apocalypses inhabit the day-to-day “secular” world?

- Are apocalypses only about the future?

KEY TERMS:

TECHNOLOGY

LABOR

EVERYDAY

REVELATION

POLITICS

This chapter concerns itself with the ways in which apocalypses manifest themselves in everyday life. As will no doubt be apparent throughout this volume, apocalypse, and its cognates apocalyptic and apocalypticism, can be understood across a range of semantic meanings, depending on the context of investigation. Apocalypse can be understood, for example, as a particular genre of discourse or literature, and apocalyptic can mean “like an apocalypse.” Or, alternatively, apocalyptic can refer to a kind of sentiment involving or relating to the “end of the world” in some sense. For the purposes of this chapter, however, apocalypse is understood generally as a form of revelation. As such, in the exploration of everyday apocalypses, we must always ask what is uncovered or revealed? Who is revealing and who is receiving revelation? And what are the media through which such communication is occurring or being covered up?

Typically, when we think about apocalypses, we think of some cataclysmic event having to do with the distant future: flying saucers or the return of vengeful gods signaling the world’s end. But this is not always so; rather apocalypses are very often about the present-day reality of those imagining them. In order to demonstrate this point, I want to introduce the mirror image of apocalypse: nostalgia. Naturally, we tend to think of nostalgia as having to do with the past, but, again, this is not entirely the case. This chapter suggests that both of these complex concepts—apocalypse and nostalgia—are less about the past or the future and more about an understanding of the present moment, and the politics of its organization. In both apocalypse and nostalgia, the past and the future are used to leverage present concerns and highlight unease with current states of affairs. Two examples from the world of film best demonstrate this.

Woody Allen’s clever romantic comedy, Midnight in Paris (2011), is a story about Gil Pender, an aspiring novelist who has settled into a mediocre career as a Hollywood screenwriter, and his growing dissatisfaction with his current life and relationships. Pender and his fiancée, Inez, along with her family, are in Paris, vacationing and wedding planning. Pender, however, is seeking inspiration for his long-neglected novel. The plot is set into motion when late one night, Pender wanders the Parisian streets a bit drunk. At the stroke of midnight, he is met by a group in a Peugeot Type 176, who invite him to a party and magically transport him back into Paris of the 1920s. There, he meets Cole Porter, Alice B. Toklas, Josephine Baker, F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, Salvador Dalí, Pablo Picasso, Luis Buñuel, and, most notably, the woman he ends up thinking he falls for—Adriana.

As the story progresses, Gil declares his love for Adriana. As he does, a horse-drawn carriage appears and transports them back to the 1890s, La Belle Époque of Paris. The two meet Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Paul Gauguin, and Edgar Degas, who offer Adriana the opportunity to design costumes for the ballet. Adriana is enthralled by the offer and the allure of their company, while Gil tries to convince her to return to the 1920s for a life together. Adriana wishes to stay on account of her belief that the 1890s were the “greatest, most beautiful [years] Paris has ever known.” For her, the 1920s is a generation that “is empty and has no imagination,” just as dull as 2010 is for Gil. Gil is dumfounded hearing this, and it is at this point that Gil is met with something of an insight and asks their three new friends what they think the best era is. The three collectively agree it has to be the Renaissance. Gil is then confronted with the truth of the first lines of the novel he has been attempting to write:

Gil’s insight is that “the present is a little unsatisfying because life is unsatisfying.” And to be happy in the past is, in fact, an illusion because those in that period—in that past—are just as unsatisfied with their era as we are with ours. Seeking happiness in the past is nothing other than a statement of unhappiness in the present. In other words, finding a home in some “golden age” amounts to little more than a realization of alienation from one’s contemporary surroundings.

The leveraging of time with respect to apocalypses is well-illustrated in Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979). The film begins and ends with the haunting sounds of the Doors performing “This is the End” (1967). Coppola’s use of the song communicates that the apocalypse, understood in this sense as the undoing of the world, is not some distant spiritual interruption into the material world. It is not some “religious” rupture in the “secular” political order. Rather, the horrors of the material world and social order—in this case, the political chaos of the Vietnam War—are themselves the cataclysm. The revelation is that the end is not to come. The end is here. This is the end. The apocalypse, according to Coppola and protesters of the Vietnam War, is now. The devils who have ushered in its arrival are politicians with horn-rimmed glasses and shuffling papers.

Why begin a chapter on apocalypses with a reflection on Woody Allen’s staging of nostalgia and Francis Ford Coppolla’s imagination of the arrival of the apocalypse? When we hear words like “apocalypse,” we tend to think of them as forms of religious thought. Religion, whatever it might mean, is, in many respects, a matter of assorting meaning to time—or a way of allocating time meaningfully. Likewise, the complex “religious” symbols and rituals are about ascribing meaning to and properly dividing time. Apocalypses, likewise, are about measuring the meaning of time. They are about ordering and periodizing time according to some predisposed meaning. And yet, as with nostalgia and the past, apocalypses are about imagining things as they might one day be in order to grapple with the way things currently are. The projections of the future in apocalypses thus reveal the politics of the present by the author(s)/communities who wrote and read those apocalypses. Put another way, apocalypses are a means of social exploration and organization. One of the goals of this chapter is to demystify this religious-sounding word a bit and to demonstrate how apocalypses are about real-world and real-time happenings and relationships, by showing how apocalypses have impacted contemporary society at practical and policy-making levels. In particular, we will consider how machines, technology, and the perceived effect of each upon labor, have appeared in a range of nostalgic and apocalyptic tones.

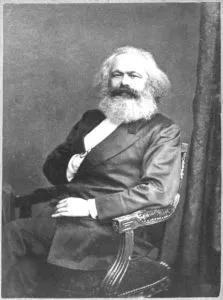

Karl Marx (1818–83) begins our exploration of the relationship between machines, labor, and apocalypse. In Marx’s worldview, the machine plays a central role in the historical development of labor. Throughout his writings, Marx reveals the machine to be a major contributor in what he perceives to be the demise of human labor conditions.

He begins the fifteenth chapter of his first volume of Capital (1867) by quoting John Stuart Mill’s Principles of Political Economy (1848):

Marx suggests that, in accordance with the system of capital, machinery was introduced to increase relative surplus value of the capitalist—not to lighten human labor. It is the “immanent drive and constant tendency of capital to raise the productive power of labor” by increasing the productivity and efficiency of the production process (Marx, Capital 1 [(1867) 1992], 436–37). Machinery was, therefore, a logical and, indeed, necessary movement arising within the very dynamics of capitalism. In Marx’s view, the machine was an abstraction of the human labor process into mechanized forms, which had the effect of transforming the human into a cog in this new, mechanized system of labor. With production becoming increasingly mechanized, the need for human labor decreased—or, at least, was made irregular. However, the shrinking of the labor force into an “industrial reserve army” through the expansion of mechanization produced overwork for those attending to the maintenance of these expensive machines.

As Marx saw it, the machine, while shrinking the labor force, also enlarged the destabilized workforce by including women and children. Jobs once requiring the strength of grown men now enlisted the cheaper labor of women and children. Owing to its “perpetual motion,” the machine prolongs the workday, which in turn, intensifies human labor. This is, for Marx, a great paradox:

Marx thus viewed the end of capitalism as an inevitable collapse, owing to the contradictions created between the wealth produced by the increasing productivity of labor itself, and the collective misery experienced by laborers. In Volume Three of Capital (1894), Marx states that competition among capitalists drives an increased desire to trim margins and increase productivity, and introduces greater levels of mechanized labor, thus alienating more and more laborers. Here, Marx envisioned a future in which the value of the means of production would rise above the value of labor. Such a view of the future labor market was certainly an indictment on present working conditions, as Marx understood them. The machine, far from improving labor conditions, was inevitably bringing about the demise of the worker—and, of course, the social order!

Marx considers this further in Section 5 of chapter 15 of Volume One, “The Strife between Workman and Machine.” Here, Marx suggests the “contest between the capitalist and the wage-laborer dates back to the very origins of capital” itself (Ibid., 426). It was only with the introduction of machinery, however, that workers began to fight back against the “material embodiment of capital” and the instrument of labor itself: namely, the machine. For Marx, the “self-expansion of capital by means of machinery is thenceforward directly proportional to the number of the workpeople, whose means of livelihood have been destroyed by that machinery” (Ibid., 466). Machinery perpetually expands into new markets of production, thus pitching the worker and machine in a thorough-going “antagonism” (Ibid., 432, 442, 490, 493–95). The advent of the machine positions the worker in a brutal revolt against the instruments of labor as the “instrument of labor strikes down the laborer” (Ibid., 466–67). Marx turns to the technical progress of the English cotton industry in 1860s to suggest that machinery is not only a competitor with the worker, but an inimical power to the worker.

In “The Fragment on Machines” in the so-called Grundrisse (Marx finished a draft of it in 1858, but it was not published until 1939...