Design Research Through Practice

From the Lab, Field, and Showroom

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Design Research Through Practice

From the Lab, Field, and Showroom

About this book

Design Research Through Practice: From the Lab, Field, and Showroom focuses on one type of contemporary design research known as constructive design research. It looks at three approaches to constructive design research: Lab, Field, and Showroom. The book shows how theory, research practice, and the social environment create commonalities between these approaches. It illustrates how one can successfully integrate design and research based on work carried out in industrial design and interaction design.The book begins with an overview of the rise of constructive design research, as well as constructive research programs and methodologies. It then describes the logic of studying design in the laboratory, design ethnography and field work, and the origins of the Showroom and its foundation on art and design rather than on science or the social sciences. It also discusses the theoretical background of constructive design research, along with modeling and prototyping of design items. Finally, it considers recent work in Lab that focuses on action and the body instead of thinking and knowing.Many kinds of designers and people interested in design will find this book extremely helpful.- Gathers design research experts from traditional lab science, social science, art, industrial design, UX and HCI to lend tested practices and how they can be used in a variety of design projects- Provides a multidisciplinary story of the whole design process, with proven and teachable techniques that can solve both academic and practical problems- Presents key examples illustrating how research is applied and vignettes summarizing the key how-to details of specific projects

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

|

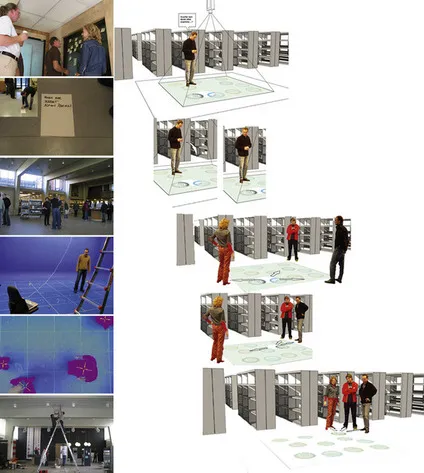

| Figure 1.1 iFloor being designed. Left column: workshops, bodystorming, site visit, technical prototyping, what the computer saw, and building the system into Aarhus City Library. Right column: use scenario. |

|

| Figure 1.2 Picture of iFloor in Danish Design Centre’s Design Prize booklet, 2004. |

|

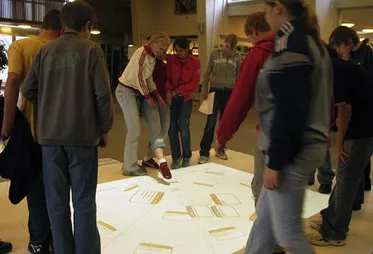

| Figure 1.3 iFloor in action. Here seventh graders are exploring the floor. |

1.1. Beyond Research Through Design

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Table of Contents

- Front-matter

- Copyright

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1. Constructive Design Research

- 2. The Coming of Age of Constructive Design Research

- 3. Research Programs

- 4. Lab

- 5. Field

- 6. Showroom

- 7. How to Work with Theory

- 8. Design Things

- 9. Constructive Design Research in Society

- 10. Building Research Programs

- References

- Index