![]()

1

THE SHAPE OF THINGS

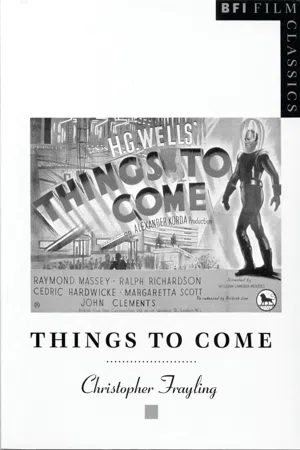

When British cinemagoers first saw William Cameron Menzies' version of H. G. Wells' Things to Come in March 1936, they would also have seen – as part of the full supporting programme – an issue of the newsreel March of Time (British issue number 5) entitled England's Hollywood.

It began with shots of cloth-capped workers and aproned crasftsmen happily going through a gate and back to work. 'On the outskirts of London,' said the optimistic commentary, 'thousands of workers of various trades and callings find employment in what is the newest and most picturesque of British industries.' Over a sequence which showed elaborate film sets being constructed, the commentary went on: 'And here each time a camera turns, it is a manifestation of a British victory in conquering for England an industry and source of revenue which was almost entirely in foreign hands only a decade ago.' A fleet of gigantic black flying fortresses, powered by four propellers apiece and looking like streamlined Odeon cinemas in the sky, flew across the screen with a distinctive humming sound as the voice-over intoned: 'Today, even teaching Hollywood new tricks of production, as in Alexander Korda's Things to Come, England takes her share of the English-speaking market, for her producers are giving the public films that the Americans cannot supply. British films with proper British taste and British accents.'

Shots of black-shirted aviators looking down from a promenade deck and of Ralph Richardson in a tin hat – with a Tudor Rose emblem stuck onto it – watching the skies were followed by a sequence showing Korda's post-production team busily assembling a complete cut of the film. Then Alexander Korda himself, in tortoise-shell rimmed spectacles, seated at his executive desk, cigar in one hand, bound script of Things to Come in the other: 'Alexander Korda, director of London Film Productions Limited, in 1932 founded his own company and the following year produced The Private Life of Henry VIII.' As Percy Grainger's well-known tune Country Gardens played softly in the background, the audience could see the component parts of Denham studios being put together: a large sound-stage, a board with 'Denham' painted on it, a back-lot, acres of scaffolding. 'At Denham, he is building with the backing of the Prudential Assurance Company and Sir Connaught Guthrie what are reported to be England's largest studios.' Then over a shot of Alexander Korda, his younger brother Vincent (the film's 'designer of settings'), Georges Périnal (director of photography), William Cameron Menzies (director) and H. G. Wells – all standing, somewhat stiffly, behind a mahogany desk on which some paper designs for Things to Come were spread out – the commentary continued: 'Today, England's movie-makers approach their problem with imagination as well as money. And in their ranks is one of Great Britain's foremost imaginations. Voice to the future of British cinema is given by a British author of world renown -who has now given up writing books entirely in favour of the cinema, Mr H. G. Wells. Just back from inspecting America's Hollywood, as the guest of Charlie Chaplin.'

The 69-year-old Wells was wearing a pin-striped suit and a club tie; he looked tubby, his unregulated moustache was going grey and he had noticeable bags under his eyes, but his gift for rhetoric and distinctive, slightly Kentish and more than slightly squeaky voice – as heard on BBC radio broadcasts since 1929 – came over as memorably as ever. Plus his well-known ability to think in paragraphs. He wasn't reading a script, but sounded as though he was. 'At the present time,' he lectured to camera, 'there are great general interests which oppress men's minds – excite and interest them. There's the onset of war, there's the increase of power, there's the change of scale and the change of conditions in the world. And in one or two of our films here, we've been trying without any propaganda or pretension or preachment of any sort, we've been trying to work out some of those immense possibilities that appeal, we think, to everyman. We are attempting here the film of imaginative possibility. That, at any rate, is one of the challenges that we are going to make to our friends and rivals at Hollywood.' A montage of billboards being posted on Broadway for Korda's The Private Life of Henry VIII and The Ghost Goes West (both of which were showing in New York, in autumn 1935) accompanied the newsreel's final message: 'Eloquent proof of the British Hollywood's challenge to America's Hollywood are certain signs visible this winter in New York City … no longer weak and crippled by foreign invasion, but now actually competing even on Broadway with the best films that any land can produce. TIME MARCHES ON.'

It must have seemed ironic to those who took the main feature seriously that this hymn of praise to national economic competition should accompany Wells' Things to Come – a polemic in favour of world economic planning and a New World Order where destructive trade wars and financial conflict would become things of the past. Ironic, too, that Wells had just returned from visiting his friend Charlie Chaplin in Hollywood (in late November 1935, while post-production was being completed on Things to Come), where he noted ruefully that Charlie was 'struggling with parallel difficulties to mine', which had turned him into 'a tired man'. For Chaplin was at that time putting the finishing touches to Modern Times, his satire on automation and the American system of manufacture – both of which were models for Wells' vision of the future. Wells had recently visited Joseph Stalin, as well, and tried to persuade him that 'the technicians, scientific workers, medical men . . . aviators, operating engineers, for instance, would and should supply the best material for constructive revolution in the West, and that the dictatorship of the proletariat (as distinct from the dictatorship of technologists) was a residue of old-style thinking- both of which were key themes in Things to Come. But Comrade Stalin seemed singularly unimpressed, and in any case March of Time wouldn't have had that kind of 'world renown' in mind when it referred to 'one of Great Britain's foremost imaginations'.

England's Hollywood does, however, provide a fascinating insight into the atmosphere surrounding the making of Things to Come. Where the cloth-capped workers were concerned, production stills of the 'attack on the coal and shale pits in the Floss Valley' sequence were circulated with the caption 'Unemployed miners as film actors represent the devastated army after the World War, in Things to Come'. Del Strother, who worked as one of the trainee sound engineers on the film, recalled that he was asked to scour the streets of Isleworth to search for undernourished extras to play the victims of 'the wandering sickness' and that he had no problem at all in finding plenty of them: Wells had explicitly requested 'cadaverous people for the sick in the Pestilence Series', and Strother duly obliged. And Korda's new studio at Denham, which promised to manufacture films that would appeal beyond the limited home market, was being actively promoted as a major employer and cure for the depression. The Private Life of Henry VIII had demonstrated that 'British films with proper British taste [of a sort] and British accents', especially if they were made to look like the American ones by Hungarians with a flair for showmanship, could earn sackfuls of dollars.

Where the studio was concerned, England's Hollywood creates the impression that Things to Come was a highly appropriate inaugural production at the new facility. In fact, since the sound stages were not completed yet, the huge Everytown Square set was built on the lot at Denham in late spring 1935, and the base of the Space Gun was constructed at the same time on the hill overlooking the lot, but many of the interiors and all the special effects were filmed at Worton Hall Studio in Isleworth, where Korda had specially commissioned a silent stage of 250 × 120 feet (which was moved, intact, to Shepperton Studios in 1948 – where it is still reported to be functioning today). The earliest interiors of Things to Come were shot in autumn 1934 at the Consolidated Studio at Elstree (which Korda had hired for the purpose). Other exteriors included a derelict coal-mine in South Wales (the attack on the Hill people) and Brooklands racetrack (the two wrecked planes, following the dogfight between John Cabal's biplane and a single-wing aircraft). But the association between the seven sound stages of Denham Studios, rising out of the rubble of the depressed film industry, and the ultra-modern Everytown rising out of the rubble of world war and the neo-feudal era which succeeds it, was nevertheless a neat one: Bauhaus designer Walter Gropius informally advised Alexander Korda on the layout of the Denham laboratories (the first colour labs in Britain) just as Korda's fellow Hungarian Laszlo Moholy-Nagy had been a consultant to Corvin Studios in the suburbs of Budapest, which Korda had designed and built way back in 1917. And Things to Come was certainly the product of'imagination as well as money': it cost between £250,000 and £300,000 (estimates vary) – by far the most expensive film that Korda, or anyone else in Britain, had produced to date – and it had a shooting schedule of over a year.

The original caption read: 'Unemployed miners as film actors represent the devastated army after the World War'

As for March of Time's presentation of H. G. Wells, he was undoubtedly an 'author of world renown' by the mid-1930s, following a series of pioneering scientific romances, or more precisely scientific speculations couched in the form of best-selling stories, including The Time Machine (1895), The Island of Dr Moreau (1896), The Invisible Man (1897), The War of the Worlds (1898), The First Men in the Moon (1901), The Food of the Gods (1904) and The War in the Air (1908), plus a series of polemical exercises in political, scientific and social prediction, or 'imaginative histories', including Anticipations (1901), A Modern Utopia (1905), The New Machiavelli (1911), The Outline of History (1920 – which took the story up to the 'aeroplane-radio-linked world' of 1960), The Science of Life (1931), The Work, Wealth and Happiness of Mankind (1932) and The Shape of Things to Come (1933). These had made him an instantly recognisable name among 'a crowd of season-ticket holders . . . reading Mr Wells' latest in the first class as well as the third class compartment', as T. S. Eliot wrote, with characteristic asperity. The stories sold more, while the prophecies made the headlines. When Wells dropped in on Charlie Chaplin or Stalin or Lenin or whoever happened to be the President of the United States for a well-publicised chat about the meaning of life, it seemed the most natural thing in the world.

The attack on the coal mine, filmed in South Wales

But he had not, as the newsreel's commentary insisted, 'given up writing books entirely in favour of cinema': it would be impossible to imagine someone as obsessively prolific with the written word even contemplating such a decision. It had recently been said of him that he wrote a new book in the time it took most people to read his last one. Instead, he had turned away from fiction towards the writing of imaginative and provocative histories of the future, based on his own social and scientific background and full of fluent disillusionment with the politics, economics and societies he saw around him: from novelist to prophet. Sometimes his prophecies were open to misinterpretation: those black-shirted aviators looked suspiciously like the followers of Oswald Mosley who goose-stepped along Cable Street in London's East End later that same year. His heroic 'scientific worker' or technocrat in Things to Come was even named Oswald – but then again, one of Oswald Cabal's predecessors, the equally visionary Sydenham in the novel Joan and Peter (1918), had also been called Oswald. At the same time as extolling the virtues of a black-shirted elite, Wells wrote of the leader of the Bolshevik Revolution in his book The Shape of Things to Come: 'One name alone among those who have been prominent in our time escapes to a certain extent the indictment of this history – the name of Nicolai Lenin.' Which must mightily have confused the cardcarrying members of the British Union of Fascists.

It was true, as the newsreel commentary said, that Wells had developed a new love affair with the cinema, since Baroness Moura Budberg – his sometime lover and current secretary – had introduced him in 1934 to the notoriously persuasive Alexander Korda over a plate of sardine sandwiches in a Bournemouth teashop, with the result that Wells had signed a contract on a penny-postcard there and then. Other film versions of Wells' stories had been made before this, of course: The Invisible Thief (1909) and First Men in the Moon (1919), both French; Kipps and The Passionate Friends (both 1922, and British); The Island of Lost Souls (1932) and The Invisible Man (1933), made in Hollywood as part of the horror boom of the early sound years. And Wells himself had helped to write three shorts in 1928 – Bluebottles, Daydreams and The Tonic – co-scripted and designed by his son Frank, and which introduced Charles Laughton and Elsa Lanchester to the screen. A year later, he published The King who was King – the book of the film, based on a treatment he had written a couple of years before for an abandoned project then called The Peace of the World: on the book's jacket he had been quoted as saying, 'I believe that if I had my life over again, I might devote myself entirely to working for the cinema'- which was perhaps where the March of Time scriptwriter got the idea from. But Wells categorised the silent film versions of his books as 'amateur efforts'; he had a lot of time for James Whale's Invisible Man but this was far from enough to deflect him from a constant stream of literary productions. 'He throws off a history of the world,' wrote Jerome K. Jerome in a famous phrase, 'while the average schoolboy is learning his dates.'

It was often said of Wells that when he fell in love he tended to fall head-over-heels. According to his son Anthony West, he was 'almost sleepless with excitement' at the prospect of turning his weighty non-fiction Shape of Things to Come into a story film for Korda called Whither Mankind? (the original title) – for that was the project they had mutually agreed in Bournemouth. He started giving int...