![]()

PART

I

Fundamentals

Part I, comprising Chapters 1 to 5, serves as an extended introduction to the book. Through it we begin to develop an analysis that facilitates negotiation by drawing extensively on:

• Decision analysis—individual prescriptive decision making

• Behavioral decision theory

• Game theory—interactive decision making

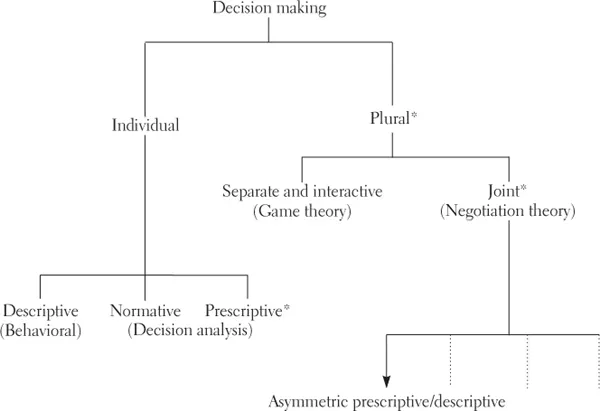

Sometimes we will think of negotiation analysis as the fourth approach to decision making.

Chapter 1 contrasts three perspectives of individual decision making:

• Normative analysis—how ideally decisions should be made (by super-rational individuals)

• Descriptive analysis—how real people actually behave (very often at variance with the normative abstraction)

• Prescriptive analysis—how real people could behave more advantageously with some systematic reflection

In group decision making, this threefold breakdown becomes more complicated. Much of the book gives partisan (prescriptive) advice to one decision maker in a group under the assumption that the other individuals are not privy to that advice and behave in a more descriptive fashion. In contrast to this orientation, the theory of games takes a jointly normative approach, assuming that both players’ behavior is super-rational.

Chapter 2 is a tutorial that develops enough of decision analysis to be of use in the rest of the book, but it leaves additional topics for later development where needed.

Chapter 3 examines real behavior and indicates that many individuals at least some of the time do not act in conformity with rational behavior—especially when uncertainties loom large. We call such examples of “deviant” behavior anomalies, biases, errors, or traps, and we try to rationalize why and how they might occur.

Chapter 4 develops many of the concepts of the noncooperative theory of games in a tutorial, self-discovery, pedagogical style; but as in Chapter 2 it leaves special topics in the theory for just-in-time later development where needed.

Chapter 5 provides an outline of the rest of the book. It introduces the concept of idealized, joint behavior, in which all protagonists in a negotiation agree to negotiate in a truly collaborative manner, agreeing to tell the truth and all of the truth. We call this joint FOTE analysis—Full, Open, Truthful Exchange. We claim that in actual deal making, in contrast to dispute settling, this ideal is often approximated, and the FOTE examination sets up an ideal against which other approaches can be compared. In later discussion, we back away from FOTE analyses to consider POTE-like behavior, in which some protagonists tell the truth but not the whole truth—Partial, Open, Truthful Exchange—leaving their bottom lines hidden from the view of others.

There is a tension in negotiations between creating actions, designed to build a bigger pie, and claiming actions, designed to obtain a large share of the pie so created. The main concern of this book is the creating function, but the claiming function cannot be ignored. Part II (Chapters 6–10) is mostly about claiming behavior for two-party negotiations; Part III (Chapters 11–17) mostly concerns creating joint gains; Part IV (Chapters 18–20) studies external interventions—how facilitators, mediators, and arbitrators can help; and Part V (Chapters 21–27) complicates it all by introducing more parties into the fray.

![]()

1

Decision Perspectives

Our primary concern in this book is to suggest how people—perhaps you—might negotiate better. Sometimes we offer partisan advice to one of the negotiating parties, who may then profit at the expense of the others. Many times the advice we give to party A might also help B—helping yourself by helping others. We get more moral satisfaction from that part. But we won’t limit ourselves to discussing only the feel-good part of negotiation. Sometimes we give advice on the process to all the parties about how they might choose to negotiate. Sometimes we give advice to external helpers (facilitators, mediators, arbitrators).

We hope our advice will help you, as negotiators:

• to understand the intricacies of the problems you face,

• to make decisions confidently in the face of complexity,

• to become able to justify your decisions convincingly to yourselves and to your constituents,

• and ultimately to conduct negotiations so that you will be satisfied with the consequences of your actions.

These benchmarks inform our purpose in crafting advice for you as negotiators, advice that deals primarily with how to help you and your constituents make better decisions in negotiations.

We are ourselves a bit uncomfortable writing as if we know better than you what you should do in your negotiations. When we say, “We advise. . .,” we usually mean, “Our analysis suggests that most people, including ourselves, would do better if they. . .”Our circumlocution is one of convenience, and an effort to avoid pedantry.

Our Approaches to Decision Making

We take a decision-making perspective; and, in so doing, we try to integrate four disciplinary approaches in our subject matter:

Decision analysis: a prescriptive approach

Behavioral decision making: a descriptive approach

Game theory: an interactive prescriptive approach

Negotiation analysis: mostly prescriptive

We shall try in this chapter to make fine distinctions among these four approaches. But despite heroic efforts to pull them apart, we ultimately come to the conclusion that the boundaries among them are so blurry that we need to integrate them in an overall approach. Such an integrated approach is a major goal of this book. Unfortunately the walls between these disciplines are not very permeable, and quite sophisticated practitioners in one domain know little about the other two related domains. Thus, for example, insights may be developed about some phenomenon in one domain that researchers think of as quite innovative without realizing that the “discoveries” are quite widely understood in the related fields. Fortunately, however, the task of integration is not overwhelmingly burdensome, because in this book we have only to draw on the more basic, less esoteric, aspects of each of these strands of inquiry. A little contribution from each discipline will collectively go a long way.

Other disciplines could be integrated with negotiation analysis as well: behavioral economics, social psychology, anthropology, and perhaps others. We don’t mean to suggest that the steps toward synthesis that we take here are exhaustive. There is plenty more to be done!

Individual Decisions

The individual (unitary) perspective. When we adopt an individual decision-making perspective, we view the world from the standpoint of a unitary decision entity. Note that the assumption of a unitary perspective does not preclude the existence of numerous individuals within the entity. For instance, we might, at one level of abstraction, advise a corporation in merger negotiations under the assumption that the corporation is a unitary decision entity. Descriptively, of course, this is not accurate. But we might prefer not to incorporate and encapsulate details of interdepartmental wrangling and boardroom spats. Adding too many details can complicate and hinder analysis. We want to tailor it to the primary needs of the decision maker. The unitary decision entity may be a family, or firm, or even a nation, depending on the problem. In summary, an individual decision-making perspective assumes the decision entity is monolithic—a blind eye is turned to internal conflict. When adopting an individual perspective, one employs the tools, techniques, and methods of decision analysis. A systematic discussion of this perspective is given in Chapter 2.

Prototypical decisions. Consider the following cases from the perspectives of the individual decision makers:

Drill or not drill. Wilder Cather, an oil wildcatter, owns the rights to drill for oil at a given site. But there is a deadline to exercise these rights. The overriding uncertainty is the amount and ease of recoverability of oil deposits at the site. He could, at a considerable expense, take seismic soundings that could inform him about the chances of finding oil.

Surgery or radiation. Sue Vivor is getting conflicting advice about what to do about her newly discovered breast cancer. Should she follow the advice of her surgeon and undergo a radical mastectomy, or try a less invasive regimen of radiation and chemo-therapy? Probabilities matter, but there are so many more concerns that she has to weigh in her difficult decision.

Invest or not. Mr. Little must decide whether to buy the store property up for sale and open a pharmacy. He has to act soon, if he acts at all. His main concern is whether Wal-Mart will open a competing enterprise in the mall not very far away. Mr. Little must worry about what Wal-Mart will do, but Wal-Mart has no concern at all about what Mr. Little will do.

In the wildcatting and medical examples, the uncertainties are not in control of someone else, some sentient being who is thinking what the decision maker is thinking and might do. It’s more complicated in the investment problem. Mr. Little must think about what Wal-Mart might do, but his analysis and subsequent action will be of little import to Wal-Mart. The decision problems of Little and Wal-Mart are only loosely coupled. Little does not have to think about what Wal-Mart is thinking about what Little is thinking.

Group Decisions

Viewing the world from a group decision-making perspective emphasizes the interactions and dynamics between multiple unitary decision entities (see Figure 1.1). The unitary entities do not need to consist of individual decision makers, but in the group setting there are, by definition, two or more unitary entities that interact to some degree. Adopting a group decision-making perspective involves more complexity than the individual perspective. Broadly defined, two approaches have developed in examining group decision making: the theory of games and the theory of negotiation.

Interactive decision making: Theory of games. Imagine a market with a few firms competing to outdo one another by competitive pricing, advertising, promotion, and the introduction of innovative products. We’re now in the domain of interactive decision making, or the theory of noncooperative games. The essence of the theory involves a set of individual decision makers (players, in the vernacular of game theory), each constrained to adopt a choice (strategy) from a specified set of choices, and the payoff to each player depends on the totality of choices made by all players. Each player must choose, sometimes not knowing the choice of the others. Each must think about what the others might do and realize that the others are, in turn, thinking about what the rest are thinking. The essence of this perspective is that although the individual decision entities make their choices separately of each other, the payoffs they receive are a function of all the players’ choices. The players are caught in a web of strategic interaction in which they have only partial control over the payoffs they receive. Individual, or separate, decisions interact to determine joint payoffs.

Figure 1.1 Perspectives on decision making. Asterisk indicates primary emphasis in this book.

Joint decision making: Negotiation theory. Consider the case of a communit...