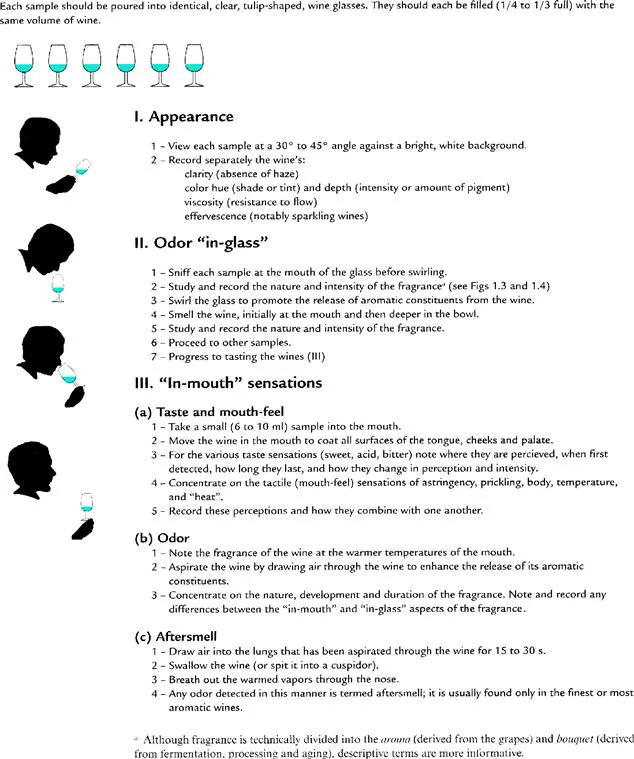

Appearance

Except for rare situations, in which color must not influence assessment, the visual characteristics of a wine are the first to be judged. To improve light transmission, the glass is tilted against a bright, white background (35° to 45° angle). This produces a curved edge of varying depths through which the wine’s appearance can be better assessed.

Visual stimuli often give a sense of pleasure and anticipation of the sensations to follow. The appearance may hint at flavor attributes as well as potential faults. An example of the influence of wine coloration on perceived quality is illustrated in Fig. 2.6. It is also well known that a deep red color increases perceived quality, even when assessed by seasoned judges. Thus, visual clues must be assessed with caution to avoid unfair prejudgment of the wine.

Clarity

All wine should be brilliantly clear. The haziness often obvious in barrel samples is of little concern. It is eliminated before bottling. Cloudiness in bottled wine is another issue. It is always considered unacceptable, despite its seldom affecting the wine’s taste or aromatic character. Because most sources of cloudiness are understood and controllable, the presence of haziness in commercial wine is uncommon. The major exception may involve some well-aged red wines that eventually “throw” sediment. However, careful decanting can avoid resuspending this material.

Color

The two most significant features of a wine’s color are its hue and depth. Hue denotes its shade or tint, whereas depth refers to the relative brightness and intensity of the color. Both aspects can provide clues to features such as grape maturity, duration of skin contact, fermentation cooperage, and wine age. Immature white grapes yield almost colorless wines, whereas fully to overmature grapes may generate yellowish wines. Increased maturity often enhances the potential color intensity of red wine. The extent to which these tendencies are realized largely depends on the duration of maceration (skin contact). Maturation in oak cooperage enhances age-related color changes, but temporarily augments color depth. During aging, golden tints in white wines increase, whereas red wines lose color density. Eventually, all wines take on tawny brown shades.

Because many factors affect wine color, it is often inappropriate to be too dogmatic about the significance of any particular shade. Only if the wine’s origin, style, and age are known, may color indicate its “correctness.” An atypical color can be a sign of several faults. The less known about a particular wine, the less significant color becomes in assessing quality. If color is too likely to be prejudicial, visual clues can be hidden by techniques such as using black glasses.

Tilting the glass has the advantage of creating a gradation of wine depths. Viewed against a bright background, the variation in depth creates a range of hues and density attributes. Pridmore et al. (2005) give a detailed discussion of these phenomena. The rim of the wine provides one of the better measures of a wine’s relative age. A purplish to mauve hue is an indicator of youth in a red wine. A brickish tint along the rim is often the first sign of aging. By contrast, observing wine down from the top is the best means of judging relative color depth.

The most difficult task associated with color assessment is expressing one’s impressions meaningfully in words. There is no accepted terminology for wine colors. Color terms are seldom used consistently or recorded in an effective manner. Some tasters place a drop of the wine on the tasting sheet. Although of comparative value, it does not even temporarily preserve an accurate record of the wine’s color.

Until a practical standard is available, use of a few simple terms is probably preferable. Terms such as purple, ruby, red, brick, and tawny; and straw, yellow, gold, and amber; combined with qualifiers such as pale, light, medium, and dark can express the standard range of red and white wine colors, respectively. These terms are fairly self-explanatory and provide an element of effective communication.

Viscosity

Wine viscosity refers to its resistance to flow. Factors such as the sugar, glycerol, and alcohol content affect this property. Typically, though, perceptible differences in viscosity are detectable only in dessert or highly alcoholic wines. Because these differences are minor and of diverse origin, they are of little diagnostic value. Viscosity is ignored by most professional tasters.

Spritz

Spritz refers to the bubbles that may form, usually along the sides and bottom of a glass, or the slight effervescence seen or detected in the mouth. Active and continuous bubbling is generally found only in sparkling wines. In the latter case, the size, number, and duration of the bubbles are important quality features.

Slight effervescence is typically a consequence of early bottling, before the excess, dissolved, carbon dioxide in newly fermented wine has had a chance to escape. Infrequently, a slight spritz may result from the occurrence of malolactic fermentation after bottling. Historically, spritz was commonly associated with microbial spoilage. Because this is now rare, a slight spritz is generally of insignificance.

Tears

Tears (rivulets, legs) develop and flow down the sides of the glass following swirling. They are little more than a crude indicator of a wine’s alcohol content. Other than for the intrigue or visual amusement they may inspire, tears are sensory trivia.

Odor

When one is assessing a wine’s fragrance, several characteristics are assessed. They include its quality, intensity, and temporal attributes. Quality refers to how the odor is described, usually in terms of other aromatic objects (e.g., rose, apple, truffle), classes of objects (e.g., flowers, fruit, vegetables), experiences (grandmother’s pumpkin pie, East Indian store, barnyard), or emotional responses (elegant, subtle, perfumed). Intensity refers to the relative magnitude of the odor. Temporal aspects refer to how the fragrance changes with time, both in quality and intensity.

Orthonasal (in-glass) Odor

Tasters are often counseled to smell the wine before swirling. This exposes the senses to the wine’s most volatile aromatics. When one is comparing several wines, it is often more convenient to position oneself over the glasses than raise each glass to one’s nose. Repeat assessment over several minutes provides the taster with an opportunity to assess one of a wine’s most ethereal attributes—development, how the fragrance changes over the course of the tasting.

The second and more important phase of olfactory assessment follows swirling of the wine. Although simple, effectively swirling usually requires practice. Until comfortable with the process, start by slowly rotating the base of the glass on a level surface. Most of the action involves a cyclical arm movement at the shoulder, while the wrist remains stationary. Holding the glass by the stem provides a good grip and permits vigorous swirling. As one becomes familiar with the process, start shifting to swirling by wrist action. Onc...