1.1 Radioactive Elements

The science of the radioactive elements and radioactivity in general is rather young compared to its maturity. In 1895 W. Roentgen was working with the discharge of electricity in evacuated glass tubes. Incidentally the evacuated glass tubes were sealed by Bank of England sealing wax and had metal plates in each end. The metal plates were connected either to a battery or an induction coil. Through the flow of electrons through the tube a glow emerged from the negative plate and stretched to the positive plate. If a circular anode was sealed into the middle of the tube the glow (cathode rays) could be projected through the circle and into the other end of the tube. If the beam of cathode rays were energetic enough the glass would glow (fluorescence). These glass tubes were given different names depending on inventor, e.g. Hittorf tubes (after Johann Hittorf) or Crookes tubes (after William Crookes). Roentgens experiments were performed using a Hittorf tube.

During one experiment the cathode ray tube was covered in dark cardboard and the laboratory was dark. Then a screen having a surface coating of barium-platinum-cyanide started to glow. It continued even after moving it further away from the cathode ray tube. It was also noticed that when Roentgens hand partly obscured the screen the bones in the nad was visible on the screen. A new, long range, penetrating radiation was found. The name X-ray was given to this radiation. Learning about this, H. Becquerel, who had been interested in the fluorescent spectra of minerals, immediately decided to investigate the possibility that the fluorescence observed in some salts when exposed to sunlight also caused emission of X-rays. Crystals of potassium uranyl sulfate were placed on top of photographic plates, which had been wrapped in black paper, and the assembly was exposed to the sunlight. After development of some of the photographic plates, Becquerel concluded (erroneously) from the presence of black spots under the crystals that fluorescence in the crystals led to the emission of X-rays, which penetrated the wrapping paper. However, Becquerel soon found that the radiation causing the blackening was not “a transformation of solar energy” because it was found to occur even with assemblies that had not been exposed to light; the uranyl salt obviously produced radiation spontaneously. This radiation, which was first called uranium rays (or Becquerel rays) but later termed radioactive radiation (or simply radioactivity)1, was similar to X-rays in that it ionized air, as observed through the discharge of electroscopes.

Marie Curie subsequently showed that all uranium and thorium compounds produced ionizing radiation independent of the chemical composition of the salts. This was convincing evidence that the radiation was a property of the element uranium or thorium. Moreover, she observed that some uranium minerals such as pitchblende produced more ionizing radiation than pure uranium compounds. She wrote: “this phenomenon leads to the assumption that these minerals contain elements which are more active than uranium”. She and her husband, Pierre Curie, began a careful purification of pitchblende, measuring the amount of radiation in the solution and in the precipitate after each precipitation separation step. These first radiochemical investigations were highly successful: “while carrying out these operations, more active products are obtained. Finally, we obtained a substance whose activity was 400 times larger than that of uranium. We therefore believe that the substance that we have isolated from pitchblende is a hitherto unknown metal. If the existence of this metal can be affirmed, we suggest the name polonium.” It was in the publication reporting the discovery of polonium in 1898 that the word radioactive was used for the first time. It may be noted that the same element was simultaneously and independently discovered by W. Marckwald who called it “radiotellurium”.

In the same year the Curies, together with G. Bemont, isolated another radioactive substance for which they suggested the name radium. In order to prove that polonium and radium were in fact two new elements, large amounts of pitchblende were processed, and in 1902 M. Curie announced that she had been able to isolate about 0.1 g of pure radium chloride from more than one ton of pitchblende waste. The determination of the atomic weight of radium and the measurement of its emission spectrum provided the final proof that a new element had been isolated.

1.2 Radioactive Decay

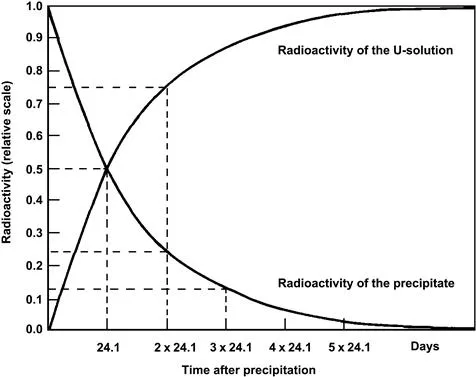

While investigating the radiochemical properties of uranium, W. Crookes and Becquerel made an important discovery. Precipitating a carbonate salt from a solution containing uranyl ions, they discovered that while the uranium remained in the supernatant liquid in the form of the soluble uranyl carbonate complex, the radioactivity originally associated with the uranium was now present in the precipitate, which contained no uranium. Moreover, the radioactivity of the precipitate slowly decreased with time, whereas the supernatant liquid showed a growth of radioactivity during the same period (Fig. 1.1). We know now that this measurement of radioactivity was concerned with only beta- and gamma-radiations, and not with the alpha-radiation which is emitted directly by uranium.

Figure 1.1 Measured change in radioactivity from carbonate precipitate and supernatant uranium solution, i.e. the separation of daughter element UX (Th) from parent radioelement uranium.

Similar results were obtained by E. Rutherford and F. Soddy when investigating the radioactivity of thorium. Later Rutherford and F. E. Dorn found that radioactive gases (emanation) could be separated from salts of uranium and thorium. After separation of the gas from the salt, the radioactivity of the gas decreased with time, while new radioactivity grew in the salt in a manner similar to that shown in Fig. 1.1. The rate of increase with time of the radioactivity in the salt was found to be completely independent of chemical processes, temperature, etc. Rutherford and Soddy concluded from these observations that radioactivity was due to changes within the atoms themselves. They proposed that, when radioactive decay occurred, the atoms of the original elements (e.g. of U or of Th) were transformed into atoms of new elements.

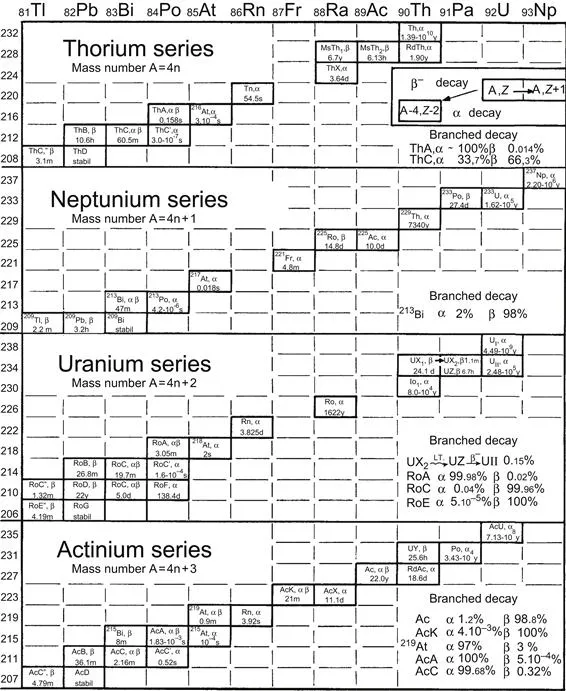

The radioactive elements were called radioelements. Lacking names for these radioelements, letters such as X, Y, Z, A, B, etc., were added to the symbol for the primary (i.e. parent) element. Thus, UX was produced from the radioactive decay of uranium, ThX from that of thorium, etc. These new radioelements (UX, ThX, etc.) had chemical properties that were different from the original elements, and could be separated from them through chemical processes such as precipitation, volatilization, electrolytic deposition, etc. The radioactive daughter elements decayed further to form still other elements, symbolized as UY, ThA, etc. A typical decay chain could be written: Ra → Rn → RaA → RaB → , etc.; see Fig. 1.2.

Figure 1.2 The three naturally occurring radioactive decay series and the man-made neptunium series. Although 239Pu (which is the parent to the actinium series) and 244Pu (which is the parent to the thorium series) have been discovered in nature, the decay series shown here begin with the most abundant long-lived nuclides.

A careful study of the radiation emitted from these radioactive elements demonstrated that it consisted of three components which were given the designation alpha (α), beta (β), and gamma (γ). Alpha-radiation was shown to be identical to helium ions, whereas beta-radiation was identical to elec...