- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Photography and Collaboration offers a fresh perspective on existing debates in art photography and on the act of photography in general. Unlike conventional accounts that celebrate individual photographers and their personal visions, this book investigates the idea that authorship in photography is often more complex and multiple than we imagine – involving not only various forms of partnership between photographers, but also an astonishing array of relationships with photographed subjects and viewers. Thematic chapters explore the increasing prevalence of collaborative approaches to photography among a broad range of international artists – from conceptual practices in the 1960s to the most recent digital manifestations. Positioning contemporary work in a broader historical and theoretical context, the book reveals that collaboration is an overlooked but essential dimension of the medium's development and potential.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Photography and Collaboration by Daniel Palmer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & History of Contemporary Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

IDEOLOGIES OF PHOTOGRAPHIC AUTHORSHIP

Announcing the invention of the daguerreotype, in a speech to the French parliament in 1839, the noted astronomer and member of the French legislature François Arago famously praised its simplicity and proposed that it could be performed by anyone, since it “presumes no knowledge of the art of drawing and demands no special dexterity” ([1839] 1980: 19). Arago was establishing what has become a recurring idea in the discourse of photography, namely, that the medium is democratic and deskilled. Indeed, one of the factors that makes photography so interesting and problematic for the historian is that this quality is viewed as a virtue in some contexts and a problem in others—depending on the writer’s investment in the dominant ideas around authorship that are in play at any given moment. This chapter seeks to make a link between the various ideologies of photographic authorship that have historically sustained the medium and the devaluation of collaborative labor that I touched on in the introduction. For while photography historians and theorists have had until very recently almost nothing to say about collaboration, the issue of authorship has long been a central fixation. Bound up with the construction of the modern author more generally— and related anxieties around originality and intentionality—it is difficult not to read this fixation as stemming from the idea that photography can be performed by anyone. Unease about photography’s democratic promise has, particularly in the hands of art historians, been overcompensated for in the figure of the bloated author.

This book is concerned with collaboration in photographic art since the rise of conceptual art in the 1960s. However, to appreciate the significance of the practices I chart in the chapters that concern these past fifty years, it is necessary to contextualize them in relation to a longer history of ideas around authorship. Most particularly, we need to understand the emphasis, in the modernist art histories of photography that still dominate the way photography is understood, on the formal qualities of individual images taken by individual photographers. As a multitude of writers since the 1970s have demonstrated (Sontag [1977]; Sekula [1978]; Phillips [1982]; Tagg [1988]; Solomon-Godeau [1991]; Batchen [2000]), this emphasis has prevented a better understanding of how photographs circulate and operate in the world, and severely limited the type of photographs considered worthy of study. Less obviously, it has fuelled the powerful stereotype of the solitary photographer. One of the reasons is that photographers themselves, eager for their own activities to be viewed as art, have often contributed to the writing of those histories. Another reason is that major art museums such as New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) have played an important role in reaffirming these histories, helping to fuel the emergence of a serious art market for photography in the 1970s (as I have already argued, the art market demands scarcity through limited and vintage editions, reinforcing the idea of the individual “visionary”). In this chapter, I conceive of seven dominant ideologies of photographic authorship: nature, law, subjectivity, worker, medium, cultural codes and software. I approach these ideas historically and chronologically, although they overlap. Like all ideologies, they are often drawn upon unconsciously. My purpose is to give a broad sense of the competing ideas fuelling authorship—particularly for readers who may not be so familiar with the history of photography—in order to better understand the conspicuously collaborative work I examine later in this book. I conclude with the productive account of authorship offered by the contemporary theorist Ariella Azoulay.

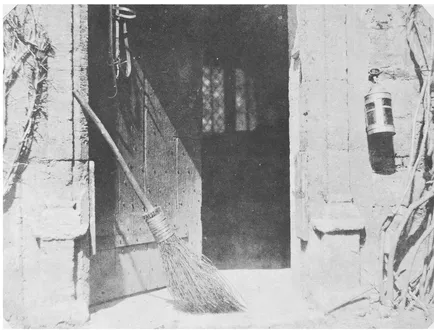

Nature as author: The sun as collaborator

The inventors of photography conceived of the medium as both an art and a science, in which the sun was the authoring agent. In 1827, in his claim to the Royal Society in England, the Frenchman Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, an avid enthusiast of the new art of lithography, gave the name héliographie to his earliest photographic experiments, from helios, meaning “sun” and graphein, meaning “write.” For the official inventors of photography, Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre and William Henry Fox Talbot, the primary author of photographs was also the sun, and more broadly nature itself (Figure 1.1). As Daguerre wrote in 1838, “The Daguerreotype is not merely an instrument which serves to draw Nature; on the contrary it is a chemical and physical process which gives her the power to reproduce herself” (quoted in Batchen 2000: 11–12). Photography historian Geoffrey Batchen has argued that photography is here “something that allows nature to be simultaneously drawn and drawing, artist and model, active and passive” (2000: 12). Talbot, in his paper presented to the Royal Society in January 1839, depicted photography as “the art of photogenic drawing” in which “natural objects may be able to delineate themselves” (quoted in Batchen 2000: 10–11). The almost ghostly drawing metaphor is underscored in Talbot’s book The Pencil of Nature (1844), which acted as a kind of prospectus stating the practical possibilities for photography and began with a notice to the reader that the plates are “impressed by the agency of Light alone without any aid whatever from the artist’s pencil. They are the sun-pictures themselves, and not, as some persons have imagined, engravings in imitation” ([1844] 1969: n.p.). Photography, which is based on the Greek words meaning “light writing,” has always been a complex marriage of nature and culture (Batchen 1997).

Figure 1.1 William Henry Fox Talbot, The Open Door, late April 1844. Salted paper print from a Calotype negative, 14.9 × 16.8 cm (5 7/ 8 × 6 5/ 8 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

Inventors who wanted to celebrate the miraculous possibilities of nature spontaneously reproducing itself understandably downplayed human effort, or the workings of the human hand. Crucially, within this “fantasy of autogenesis” (Edwards 2006: 42), it was precisely photography’s apparently objective quality that made it such a powerful medium. Indeed, the “mechanical objectivity” of the camera was recognized as valuable in the nineteenth century as part of an “insistent drive to repress the wilful intervention of the artist-author” (Daston and Gailson 2007: 121). In all sorts of contexts outside of art—in science, criminology, industry, medicine, surveillance, and other instrumental uses—the suppression of individual authorship continues to give photography its authority. In the nineteenth century, even dramatic landscape “views” were often presented anonymously, such that “the natural phenomenon, the point of interest, rises up to confront the viewer, seemingly without the mediation of an individual recorder or artist” (Krauss 1982: 314).

By the same token, photography’s mechanical nature, and the associated claim that it represented the objective manifestation of nature, prevented it from even being confused with fine art in the eyes of many influential nineteenth-century commentators. For the poet Charles Baudelaire, as for others who conceived of art as an expression of human imagination, photography’s seemingly objective nature was found fundamentally lacking. Photography was a soulless, mechanical copying of reality, both too technical and too easy to ever resemble fine art. Later, in the 1920s, the Surrealists and other avant-garde artists exploited photography’s mechanical and automatic quality—in, for example, the embrace of the photogram as a route to the unconscious. The photogram in fact continues to offer a profound metaphor for the complications of photographic authorship (Batchen 2000: 161). And yet, as Rosalind Krauss observes, the photogram “only forces, or makes explicit, what is the case of all photography” (1977: 75), namely that it is “the result of a physical imprint transferred by light reflections onto a sensitive surface.” All this is to come. In his salon review of 1859, Baudelaire memorably dismissed the new class of pseudo-artists flocking to the camera as “sun-worshippers” ([1859] 1980: 87). But there was already a more generous way of thinking about the sun’s role. The nineteenth-century French poet and political minister Alphonse de Lamartine initially accused photography of plagiarizing nature by optics (quoted in Gernsheim 1962: 64). However, he later publicly changed his mind—declaring that photography “is better than an art, it is a solar phenomenon in which the artist collaborates with the sun” (quoted in Gernsheim 1962: 65).

Law as author: The legal codification of authorship

Perhaps the most important ideology of authorship is that set down by law. As Jane M. Gaines puts it, “How do we find the author in the photographic work in order to establish that he, rather than the machine, created the photograph itself?” (1991: 44). In France, copyright law had existed since the Revolution, with the landmark law on author’s rights being enacted in 1793 (Nesbitt 1987: 230). But as the French legal scholar Bernard Edelman observes, “The eruption of modern techniques of the (re)production of the real—photographic apparatuses, cameras—surprised the law” (quoted in Gaines 1991: 45). Edelman puts it in the following way: “For French law, the crucial question was whether or not the mechanical product could be said to have anything of ‘Man’ in it at all. An authored work (it was argued) is imbued with something of the human soul, but a machine-produced work is completely ‘soulless’” (quoted in Gaines 1991: 46). Not surprisingly, given this test, photographers who wanted the legal protection offered by copyright law needed to prove somehow that their work was artistic. In other words, the relations of production demanded they set themselves up as artists, since “a soul had to be found in the mechanical act” (Gaines 1991: 47). What was a machinic act involving the duplication of the world needed to become an original production in the form of intellectual property (Gaines 1991: 47).

Photographers began testing the law immediately, and by around 1862, the French courts translated the idea of the creative soul into the concept of the “imprint of personality” (Gaines 1991: 47). Likewise, in Britain and the United States, the investment of personality became the crucial authorial deposit for intellectual property. Photography, as Gaines suggests, had been domesticated according to “existing conceptions of the world” (1991: 47). Or, as John Roberts put it more recently, “All aestheticized theories of photography as art stem from the legal codification of the photographer as creator, although this legal codification does not in itself produce the ideology of aestheticization. Aesthetic ideology and the concept of the modern, autonomous artistic subject preexist this new legislation” (2014: 175 n.2). Gaspard-Félix Tournachon, who went by the name Nadar, represents a clear example here. The entrepreneurial portrait photographer—who was a student of the painter-cum-photographer Gustave Le Gray (more on whom later)—became the best-known and most notorious photographer working in France in the nineteenth century. First opening his photographic studio in Paris in 1853, he had the artistic and intellectual aristocracy of France virtually lined up to sit for him. As he wrote of his portrait photography in 1857: “The theory of photography can be learnt in an hour, the first ideas of how to go about it in a day . . . What can’t be learnt . . . is the feeling for light—the artistic appreciation of effects produced by different or combined sources [and] the instinctive understanding of your subject” (Scharf 1976: 106). In other words, Nadar maintained that he was not simply an operator of photographic equipment, but an artist sensitive to the nuances of personal character and the artistic effects of light (Warner 2002: 89). Notably, he did not recognize any contribution from the photographed subjects toward the representation of their own image.

Once thousands of people began to depend upon photography for a living, issues around the protection of copyright became paramount. The most famous copyright case pertaining to photography in the nineteenth century involved the preeminent New York studio photographer Napoleon Sarony and his cabinet photographs of the visiting Oscar Wilde taken in 1882. Wilde’s visit to New York was a spectacular success, so much so that his image was widely sought and copied. Sarony sued a printer, Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co., for infringing his copyright by reproducing at least 85,000 unauthorized copies of the image (Gaines 1991: 52). The district court in New York in 1883 found the defendant guilty of piracy, but on appeal to the Supreme Court in 1884, Burrow-Giles argued that photographs were ineligible for copyright protection (granted by an 1865 amendment that had specifically added photographs to the list of copyrightable forms) because the Constitution only protected authors’ writings, while the photograph is a “mere mechanical reproduction” (Gaines 1991: 55). For his part, Sarony argued, among other factors, that the draperies, light and shade, Wilde’s expression, and above all his pose belonged to an “original mental conception” (Gaines 1991: 54). Indeed, Sarony dissociated himself from the mechanical apparatus—referring to how he deftly relayed his ideas to the camera operator (Gaines 1991: 72). The court agreed with Sarony that his portrait of Wilde was “an original work of art, the product of plaintiff’s intellectual invention, of which plaintiff is the author, and of a class of inventions for which the Constitution intended that Congress should secure to him the exclusive right to use, publish and sell” (Tuchman 2004). An author, according to the court ruling, is simply the one “to whom anything owes its origin” (Tuchman 2004). As Gaines (1991: 51) points out, “originality is elaborated as a defense of Sarony’s photographic artistry,” but the test of originality is a paradoxical one, rooted in both the Lockean philosophy that “man is the origin of property” (58) and the romantic individualized notion of authorial creation, rather than in the work itself.1 In this model, the rights of the photographed subject over their image are limited to an original contract (there is no evidence that Wilde knew of the court case). In short, in the photographer’s “choice” of subject and style of framing, “we have the human investment of labour . . . the private property-producing gesture” (Gaines 1991: 68). This legal codification of photography remains highly relevant to authorship today, as we will see in relation to Richard Prince’s work (Chapter 5).

Subjectivity as author: Pictorialist and modernist sensibilities

In significant respects, the history of photography has been one of applying traditional art-historical categories such as originality and style to the medium, in the face of claims that photography lacks artistic intentionality due to its mechanical nature. As we have already established, photography’s ease has always been a challenge to its status as art. If so many untrained people can take photographs, how can it be as exclusive as art? The nineteenth century is punctuated by the emergent notion of the artist-photographer, based around subjective response. In France, the landscape photographer Gustave Le Gray—who studied painting in the studio of Paul Delaroche (the painter who apocryphally claimed, upon first seeing a Daguerreotype, that “from today painting is dead”)—wrote in 1852 that “it is my deepest wish that photography, instead of falling within the domain of industry, of commerce, will be included among the arts. That is its sole, true place, and it is in that direction that I shall always endeavor to guide it” (Naef 2004: 32). In attempting to establish photography as an art form—many would-be artist-photographers argued for an analogy between painting and photography.

Figure 1.2 Henry Peach Robinson, When the Day’s Work Is Done, 1877. Albumen silver print, 56 × 74.5 cm (22 1/16 × 29 5/16 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

The English photographer Henry Peach Robinson is arguably the most emblematic nineteenth-century art-photographer. Robinson was influenced—like Julia Margaret Cameron, who could equally claim this title—by the Pre-Raphaelite painters, and started with sketches for his pictures, working out elaborate and highly detailed scenes (Figure 1.2). When the Day’s Work Is Done (1877), like his most famous work, Fading Away (1858), involved the use of models and the seamless combination of multiple separate negatives to...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Ideologies of photographic authorship

- 2 Impersonal evidence: Photography as readymade

- 3 Collaborative documents: Photography in the name of community

- 4 Relational portraiture: Photography as social encounter

- 5 Aggregated authorship: Found photography and social networks

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- Index