- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

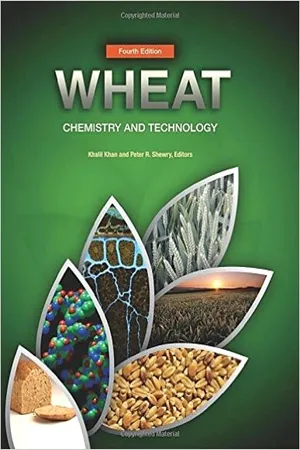

Wheat: Chemistry and Technology

About this book

Wheat science has undergone countless new developments since the previous edition was published. Wheat: Chemistry and Technology, Fourth Edition ushers in a new era in our knowledge of this mainstay grain. This new edition is completely revised, providing the latest information on wheat grain development, structure, and composition including vital peer-reviewed information not readily available online.It contains a wealth of new information on the structure and functional properties of gluten (Ch. 6), micronutrients and phytochemicals in wheat grain (Ch. 7), and transgenic manipulation of wheat quality (Ch. 12). With the new developments in molecular biology, genomics, and other emerging technologies, this fully updated book is a treasure trove of the latest information for grain science professionals and food technologists alike.Chapters on the composition of wheat—proteins (Ch. 8), carbohydrates (Ch. 9) lipids (Ch. 10), and enzymes (Ch. 11.), have been completely revised and present new insight into the important building blocks of our knowledge of wheat chemistry and technology. The agronomical importance of the wheat crop and its affect on food industry commerce provide an enhanced understanding of one of the world's largest food crop.Most chapters are entirely rewritten by new authors to focus on modern developments. This 480-page monograph includes a new large 8.5 x 11 two-column format with color throughout and an easy to read style.Wheat: Chemistry and Technology, Fourth Edition provides a comprehensive background on wheat science and makes the latest information available to grain science professionals at universities, institutes, and industry including milling and baking companies, and anywhere wheat ingredients are used. This book will also be a useful supplementary text for classes teaching cereal technology, cereal science, cereal chemistry, food science, food chemistry, milling, and nutritional properties of cereals. Cereal and food science graduate students will find Chapter 1 – "Wheat: A Unique Grain for the World particularly helpful because it provides a succinct summary of wheat chemistry.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Wheat: A Unique Grain for the World

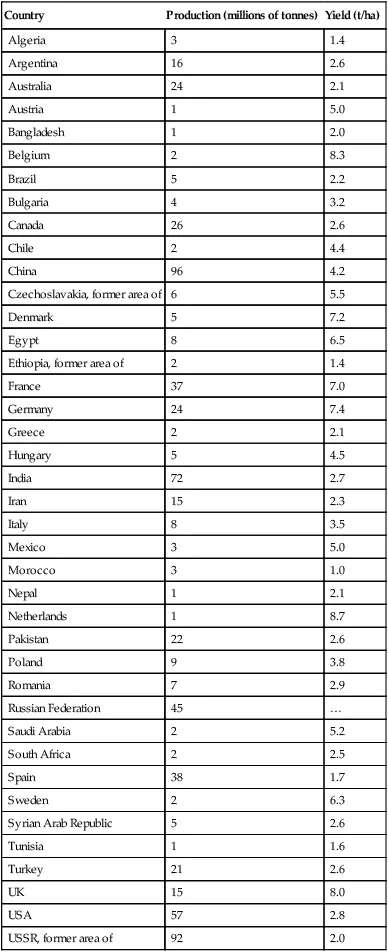

| Country | Production (millions of tonnes) | Yield (t/ha) |

| Algeria | 3 | 1.4 |

| Argentina | 16 | 2.6 |

| Australia | 24 | 2.1 |

| Austria | 1 | 5.0 |

| Bangladesh | 1 | 2.0 |

| Belgium | 2 | 8.3 |

| Brazil | 5 | 2.2 |

| Bulgaria | 4 | 3.2 |

| Canada | 26 | 2.6 |

| Chile | 2 | 4.4 |

| China | 96 | 4.2 |

| Czechoslavakia, former area of | 6 | 5.5 |

| Denmark | 5 | 7.2 |

| Egypt | 8 | 6.5 |

| Ethiopia, former area of | 2 | 1.4 |

| France | 37 | 7.0 |

| Germany | 24 | 7.4 |

| Greece | 2 | 2.1 |

| Hungary | 5 | 4.5 |

| India | 72 | 2.7 |

| Iran | 15 | 2.3 |

| Italy | 8 | 3.5 |

| Mexico | 3 | 5.0 |

| Morocco | 3 | 1.0 |

| Nepal | 1 | 2.1 |

| Netherlands | 1 | 8.7 |

| Pakistan | 22 | 2.6 |

| Poland | 9 | 3.8 |

| Romania | 7 | 2.9 |

| Russian Federation | 45 | … |

| Saudi Arabia | 2 | 5.2 |

| South Africa | 2 | 2.5 |

| Spain | 38 | 1.7 |

| Sweden | 2 | 6.3 |

| Syrian Arab Republic | 5 | 2.6 |

| Tunisia | 1 | 1.6 |

| Turkey | 21 | 2.6 |

| UK | 15 | 8.0 |

| USA | 57 | 2.8 |

| USSR, former area of | 92 | 2.0 |

WHEAT AND PEOPLE

Wheat and Human Origins

DEITIES OF WHEAT

| Family or Tribe | Genus and Species | Common Names | World Productiona (millions of tonnes) | |

| Monocotyledonous plants | ||||

| Triticeae | Triticum aestivum | Common (bread) wheat |  | 626 (all wheat) |

| Triticeae | Triticum durum | Durum (macaroni) wheat | ||

| Triticeae | xTriticosecale sp. | Triticale | 13 | |

| Triticeae | Secale cereale | Cereal rye | 15 | |

| Triticeae | Hordeum vulgare | Barley | 138 | |

| Aveneae | Avena sativa | Oats | 25 | |

| Andropogoneae | Sorghum bicolor | Sorghum | 57 | |

| Andropogoneae | Zea mays | Corn, maize | 692 | |

| Oryzeae | Oryza sativa | Rice |  | 615 (as paddy) |

| Oryzeae | Zizania aquatica | Wild rice | ||

| Eragrostideae and Paniceae | Several genera a... | |||

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Contributors

- Preface to the Fourth Edition

- Preface to the Third Edition

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Preface to the First Edition

- Chapter 1: Wheat: A Unique Grain for the World

- Chapter 2: The Wheat Crop

- Chapter 3: Development, Structure, and Mechanical Properties of the Wheat Grain

- Chapter 4: Criteria of Wheat and Flour Quality

- Chapter 5: Wheat Flour Milling

- Chapter 6: Structure and Functional Properties of Gluten

- Chapter 7: Micronutrients and Phytochemicals in Wheat Grain

- Chapter 8: Wheat Grain Proteins

- Chapter 9: Carbohydrates

- Chapter 10: Wheat Lipids

- Chapter 11: Enzymes and Enzyme Inhibitors Endogenous to Wheat

- Chapter 12: Transgenic Manipulation of Wheat Quality

- Index