- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Gluten-Free Baked Products

About this book

One of the most rapidly growing segments in the food industry is gluten-free baked products. These goods not only cater to those with medical needs, from celiac disease to gluten intolerance; they also cater to the millions of individuals who seek a gluten-free diet.Gluten-Free Baked Products is a practical guide on the development, manufacturing, and marketing of gluten-free baked products. The book gives readers an entry-level understanding of gluten-free product requirements, their production, and the breadth of ingredients available to baked product developers.This highly relevant book was written as an initial reference for food scientists, including those who need an introduction to gluten-free product development. It was also written as a general reference to those who are indirectly involved with gluten-free products, such as marketers, consultants, and quality assurance and regulatory professionals. Nutrition enthusiasts and consumers following a gluten-free diet for medical reasons will also find this book useful.Gluten-Free Baked Products can serve as a supplemental resource for students and faculty of general food science courses, as well as those covering product development, food allergies, and autoimmune conditions.Whether you are a student, professional in the food industry, or nutrition enthusiast, this book offers an easy way to understand the complex world of gluten-free bakingCoverage includes: - A detailed discussion on celiac disease, wheat allergies, and gluten intolerance, including symptoms, diagnosis, and nutritional deficiencies- A marketing perspective on the consumer segments of gluten-free products, as well as the market size and growth trends- Formulations and processing of gluten-free breads, snacks, and pasta products, as well as cookies, cakes, and other batter-based products- Manufacturing and supply chain best practices, certification procedures, regulations, and labeling requirements- A comprehensive discussion of the ingredients used when formulating gluten-free products, including flours, starches, maltodextrins, corn/maize, millet, oats, rice, sorghum, teff, pseudocereals, inulin, tubers, legumes, noncereal proteins, enzymes, and gums/hydrocolloids

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Gluten Intolerance, Celiac Disease, and Wheat Allergy

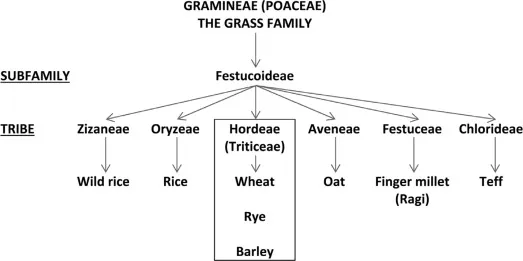

Gluten

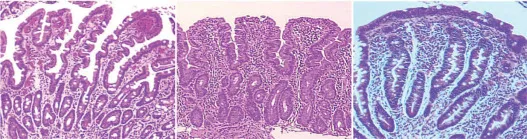

Celiac Disease

Factor 1: Genetic Predisposition

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Gluten Intolerance, Celiac Disease, and Wheat Allergy

- Chapter 2: The Gluten-Free Market and Consumer

- Chapter 3: Gluten-Free Ingredients

- Chapter 4: Gluten-Free Bakery Product Formulation and Processing

- Chapter 5: Gluten-Free Pasta and Snacks

- Chapter 6: Gluten-Free Best Practices, Regulations, and Labeling

- Index