- 464 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Lawrie's Meat Science

About this book

Lawrie's Meat Science has established itself as a standard work for both students and professionals in the meat industry. Its basic theme remains the central importance of biochemistry in understanding the production, storage, processing and eating quality of meat. At a time when so much controversy surrounds meat production and nutrition, Lawrie's meat science, written by Lawrie in collaboration with Ledward, provides a clear guide which takes the reader from the growth and development of meat animals, through the conversion of muscle to meat, to the point of consumption.The seventh edition includes details of significant advances in meat science which have taken place in recent years, especially in areas of eating quality of meat and meat biochemistry.

- A standard reference for the meat industry

- Discusses the importance of biochemistry in production, storage and processing of meat

- Includes significant advances in meat and meat biochemistry

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

1.1 Meat and muscle

Meat is defined as the flesh of animals used as food. In practice this definition is restricted to a few dozen of the 3000 mammalian species; but it is often widened to include, as well as the musculature, organs such as liver and kidney, brains and other edible tissues. The bulk of the meat consumed in the United Kingdom is derived from sheep, cattle and pigs: rabbit and hare are, generally, considered separately along with poultry. In some European countries (and elsewhere), however, the flesh of the horse, goat and deer is also regularly consumed; and various other mammalian species are eaten in different parts of the world according to their availability or because of local custom. Thus, for example, the seal and polar bear are important in the diet of the Inuit, and the giraffe, rhinoceros, hippopotamus and elephant in that of certain tribes of Central Africa: the kangaroo is eaten by the Australian aborigines: dogs and cats are included in the meats eaten in Southeast Asia: the camel provides food in the desert areas where it is prevalent and the whale has done so in Norway and Japan. Indeed human flesh was still being consumed by cannibals in remote areas until only recently past decades; (Bjerre, 1956).

Very considerable variability in the eating and keeping quality of meat has always been apparent to the consumer; it has been further emphasized in the last few years by the development of prepackaging methods of display and sale. The view that the variability in the properties of meat might, rationally, reflect systematic differences in the composition and condition of the muscular tissue of which it is the post-mortem aspect is recognized. An understanding of meat should be based on an appreciation of the fact that muscles are developed and differentiated for definite physiological purposes in response to various intrinsic and extrinsic stimuli.

1.2 The origin of meat animals

The ancestors of sheep, cattle and pigs were undifferentiated from those of human beings prior to 60 million years ago, when the first mammals appeared on Earth. By 2–3 million years ago the species of human beings to which we belong (Homo sapiens) and the wild ancestors of our domesticated species of sheep, cattle and pigs were probably recognizable. Palaeontological evidence suggests that there was a substantial proportion of meat in the diet of early Homo sapiens. To tear flesh apart, sharp stones – and later fashioned stone tools – would have been necessary. Stone tools were found, with the fossils of hominids, in East Africa (Leakey, 1981).* Our ape-like ancestors gradually changed to present day human beings as they began the planned hunting of animals. There are archaeological indications of such hunting from at least 500,000 bc. The red deer (Cervus elaphus) and the bison (referred to as the buffalo in North America) were of prime importance as suppliers of hide, sinew and bone, as well as meat, to the hunter-gatherers in the areas which are now Europe and North America, respectively (Clutton-Brock, 1981). It is possible that reindeer have been herded by dogs from the middle of the last Ice Age (about 18,000 bc), but it is not until the climatic changes arising from the end of this period (i.e. 10,000–12,000 years ago) that conditions favoured domestication by man. It is from about this time that there is definite evidence for it, as in the cave paintings of Lascaux.

According to Zeuner (1963) the stages of domestication of animals by man involved first loose contacts, with free breeding. This phase was followed by the confinement of animals, with breeding in captivity. Finally, there came selected breeding organized by man, planned development of breeds having certain desired properties and extermination of wild ancestors. Domestication was closely linked with the development of agriculture and although sheep were in fact domesticated before 7000 bc, control of cattle and pigs did not come until there was a settled agriculture, i.e. about 5000 bc.

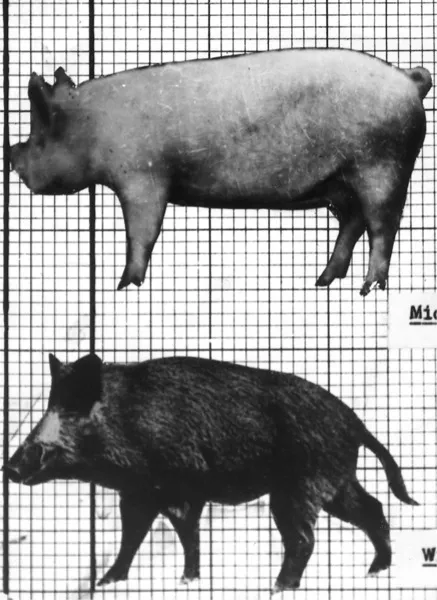

Domestication alters many of the physical characteristics of animals and some generalization can be made. Thus, the size of domesticated animals is, usually, smaller than of their wild ancestors.** Their colouring alters and there is a tendency for the facial part of the skull to be shortened relative to the cranial portion; and the bones of the limbs tend to be shorter and thicker. This latter feature has been explained as a reflection of the higher plane of nutrition which domestication permits; however, the effect of gravity may also be important, since Tulloh and Romberg (1963) have shown that, on the same plane of nutrition, lambs to whose back a heavy weight has been strapped, develop thicker bones than controls. (As is now well documented, exposure to prolonged periods of weightlessness causes loss of bone and muscle mass.) Many domesticated characteristics are, in reality, juvenile ones persisting to the adult stage. Several of these features of domestication are apparent in Fig. 1.1 (Hammond, 1933–4). It will be noted that the domestic Middle White pig is smaller (45 kg; 100 lb) than the wild boar (135 kg; 300 lb), that its skull is more juvenile, lacking the pointed features of the wild boar, that its legs are shorter and thicker and that its skin lacks hair and pigment.

Fig. 1.1 Middle White Pig (aged 15 weeks, weighting 45 kg; 100 lb) and Wild Boar (adult, weighting about 135 kg; 300 lb), showing difference in physical characteristics. Both to same head size (Hammond, 1933–4). Courtesy of the late Sir John Hammond.

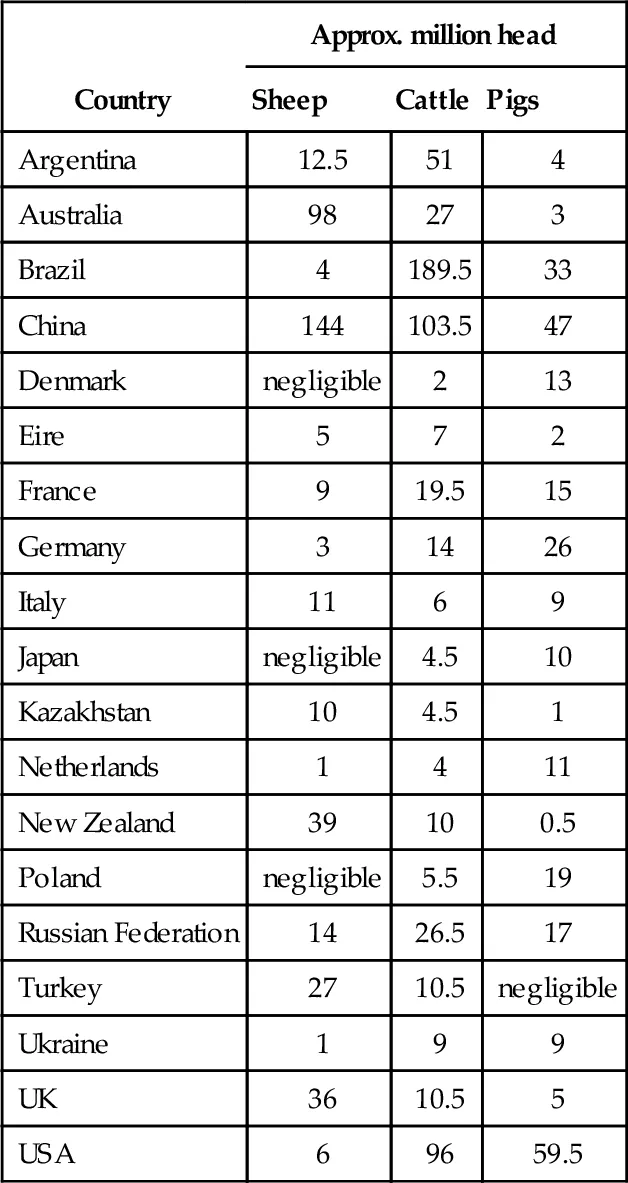

Apart from changing the form of animals, domestication encouraged an increase in their numbers for various reasons. Thus, for example, sheep, cattle and pigs came to be protected against predatory carnivores (other than man), to have access to regular supplies of nourishing food and to suffer less from neonatal losses. Some idea of the present numbers and distribution of domestic sheep, cattle and pigs is given in Table 1.1 (Anon., 2003).

Table 1.1

Numbers of sheep, cattle and pigs in various countries, 2003

| Country | Approx. million head | ||

| Sheep | Cattle | Pigs | |

| Argentina | 12.5 | 51 | 4 |

| Australia | 98 | 27 | 3 |

| Brazil | 4 | 189.5 | 33 |

| China | 144 | 103.5 | 47 |

| Denmark | negligible | 2 | 13 |

| Eire | 5 | 7 | 2 |

| France | 9 | 19.5 | 15 |

| Germany | 3 | 14 | 26 |

| Italy | 11 | 6 | 9 |

| Japan | negligible | 4.5 | 10 |

| Kazakhstan | 10 | 4.5 | 1 |

| Netherlands | 1 | 4 | 11 |

| New Zealand | 39 | 10 | 0.5 |

| Poland | negligible | 5.5 | 19 |

| Russian Federation | 14 | 26.5 | 17 |

| Turkey | 27 | 10.5 | negligible |

| Ukraine | 1 | 9 | 9 |

| UK | 36 | 10.5 | 5 |

| USA | 6 | 96 | 59.5 |

1.2.1 Sheep

Domesticated sheep belong to the species Ovis aries and appear to have originated in western Asia. The sheep was domesticated with the aid of dogs before a settled agriculture was established. The bones of sheep found at Neolithic levels at Jericho, have been dated as being from 8000–7000 BC (Clutton-Brock, 1981). Four main types of wild sheep still survive – the Moufflon in Europe and Persia, the Urial in western Asia and Afghanist...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Preface to seventh edition

- Preface to first edition

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Factors influencing the growth and development of meat animals

- Chapter 3: The structure and growth of muscle

- Chapter 4: Chemical and biochemical constitution of muscle

- Chapter 5: The conversion of muscle to meat

- Chapter 6: The spoilage of meat by infecting organisms

- Chapter 7: The storage and preservation of meat: I Temperature control

- Chapter 8: The storage and preservation of meat: II Moisture control

- Chapter 9: The storage and preservation of meat: III Direct microbial inhibition

- Chapter 10: The eating quality of meat

- Chapter 11: Meat and human nutrition

- Chapter 12: Prefabricated meat

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Lawrie's Meat Science by R. A. Lawrie,David Ledward in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Food Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.