- 608 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals in Food

About this book

The rise in the incidence of health problems such as reproductive disorders and testicular and breast cancer has been linked by some to endocrine disrupting chemicals in the environment. The role of food in transmitting these chemicals is uncertain and a topic of considerable research. This important book addresses key topics in this area.The first part of the book reviews the impacts of endocrine disrupting chemicals on health and behaviour, with chapters on the effect of dietary endocrine disruptors in such areas as the developing foetus, cancer and bone health. Parts two and three focus on the origin and analysis of endocrine disruptors in food products and risk assessment. Topics addressed include surveillance, analysis techniques such as biosensors, exposure assessment and the relevance of genetics, epigenetics and genomic technologies to the study of endocrine disrupting chemicals. Concluding chapters discuss examples of selected endocrine disrupting chemicals associated with food, such as dioxins, polychlorinated biphenyls and brominated flame retardants, bisphenol A and phytoestrogens and phytosterols.With its distinguished editor and international team of contributors, Endocrine-disrupting chemicals in food is an essential reference for all those concerned with ensuring the safety of food.

- Reviews the impacts of endocrine disrupting chemicals on health and behaviour including cancer and reproductive disorders

- Addresses the origin and analysis of endocrine disruptors with chapters on surveillance and analysis techniques

- Examines the relevance of genetics, epigenetics and genomic technologies to endocrine disrupting chemicals

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals in Food by I Shaw in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Food Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Endocrine disruptors, health and behaviour

1

The effect of dietary endocrine disruptors on the developing fetus

I. Shaw, University of Canterbury and University of Auckland, New Zealand

B. Balakrishnan and M.D. Mitchell, University of Auckland, New Zealand

Abstract

It is accepted that both natural and synthetic endocrine disruptors are present in the food we eat, and that they are likely to have a pharmacological impact on the consumer. The magnitude of this impact is a cause of great controversy at present. Much of the debate has focused on the direct impact of endocrine disruptors on the consumer; this chapter speculates on possible impacts on the developing fetus that might lead to effects that manifest themselves much later in life.

Key words

in utero effects

placental barrier

placental metabolism

developing fetus – effects on human development

protection of fetus

1.1 Introduction

The first evidence of adverse effects of phytoestrogens in animal reproduction came over 60 years ago from Western Australia where male rams, feeding on clover pasture, became feminised and unable to breed. The cause of this phenomenon was eventually identified as the high levels of the isofavones genistein and diadzein present in clover (Bennets et al., 1946). Fifty years later Guillette et al. (1994) showed in their seminal work that alligators in Lake Apopka in the Florida Everglades have smaller penises than those from nearby Lake Woodruff, not because of direct effects of xenoestrogenic contaminants (e.g. dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, DDT) in Lake Apopka upon the alligators, but rather due to an effect of the contaminants on the developing egg. The resultant alligators displayed reduced testosterone levels, leading in turn to under-developed penises. This illustrates well the potential effects of in utero exposure to environmental endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) on adult reproductive function.

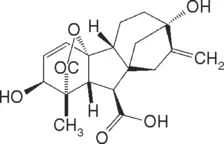

A quite different form of long-term impact on reproduction following exposure to EDCs is the potential for estrogen mimics in food plants to signal to their consumers that in the following year there will be a bumper crop, and therefore that offspring are likely to survive because of the plentiful supply of food. There are many examples of this recently discovered phenomenon. For example the kakapo (Strigops habroptilus), a rare New Zealand flightless parrot, ovulates when rimu (Dacrydium cupressinum; a large rainforest podocarp tree) is likely to produce a good crop of seeds in the following year (Sutherland, 2002). Through this ingenious adaptation, the success of the offspring is supported by a plentiful supply of food in the season when the egg hatches. It is possible that the signal is the plant hormone gibberellic acid, which is produced at higher levels in the year preceding extensive fruiting. Gibberellic acid is a 17β-estradiol mimic (Fig. 1.1), and when consumed by the would-be mother kakapo might stimulate ovulation and egg-laying. There are other similar examples: for instance the grey squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) eats the tips of pine trees. If the tips are high in gibberellic acid it is thought that this signals a good crop of pine cones the following season, and also stimulates the squirrels to reproduce (Richard Pharis, University of Calgary, USA, personal communication). The offspring are assured a good supply of seeds from the cones and so are more likely to thrive. This all makes good evolutionary sense and is a good example of exposure to endocrine disruptors affecting a future generation.

Sumpter and Jobling (1995) commented that aquatic organisms live in ‘a sea of estrogens’. They were referring to the multifarious estrogen mimics that are present in sewage effluent and so find their way into rivers and streams; human consumers are as a result also exposed via drinking water that originates from these aquatic environments. In addition, there are estrogenic pesticide residues in our food (e.g. DDT), and myriad natural endocrine disruptors in the plants and animals we eat (Thomson et al., 2003). Sometimes we forget that the meat from female food animals and their milk all contain relatively high concentrations of 17β-estradiol (and other hormones). Therefore estrogenic chemicals are all around; we are exposed to them continuously.

The first potential effects of EDCs in humans were suggested by Carlsen et al. (1992), who reported a decline in semen quality during the preceding 50 years. The experimental design of this study has, however, been criticised (Pflieger-Bruss et al., 2004). Interestingly, semen quantity in bulls and other animals has remained unchanged over the corresponding 50-year period. It is now largely accepted that human sperm quality has declined over the past five or six decades, but th...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Related titles

- Copyright

- Contributor contact details

- Editor’s dedication

- Introduction

- Acknowledgements

- Part I: Endocrine disruptors, health and behaviour

- Part II: Origin and analysis of endocrine disruptors in food products

- Part III: Risk assessment of endocrine disruptors in food products

- Part IV: Examples of endocrine-disrupting chemicals associated with food and other consumer products

- Index