- 472 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The development of high-quality foods with desirable properties for both consumers and the food industry requires a comprehensive understanding of food systems and the control and rational design of food microstructures. Food microstructures reviews best practice and new developments in the determination of food microstructure.After a general introduction, chapters in part one review the principles and applications of various spectroscopy, tomography and microscopy techniques for revealing food microstructure, including nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) methods, environmental scanning electron, probe, photonic force, acoustic, light, confocal and infrared microscopies. Part two explores the measurement, analysis and modelling of food microstructures. Chapters focus on rheology, tribology and methods for modelling and simulating the molecular, cellular and granular microstructure of foods, and for developing relationships between microstructure and mechanical and rheological properties of food structures. The book concludes with a useful case study on electron microscopy.Written by leading professionals and academics in the field, Food microstructures is an essential reference work for researchers and professionals in the processed foods and nutraceutical industries concerned with complex structures, the delivery and controlled release of nutrients, and the generation of improved foods. The book will also be of value to academics working in food science and the emerging field of soft matter.

- Reviews best practice and essential developments in food microstructure microscopy and modelling

- Discusses the principles and applications of various microscopy techniques used to discover food microstructure

- Explores the measurement, analysis and modelling of food microstructures

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Microstructure and microscopy

1

Environmental scanning electron microscopy (ESEM): principles and applications to food microstructures

D.J. Stokes, FEI Company, The Netherlands

Abstract:

This chapter introduces some basic principles of scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and its extension to environmental scanning electron microscopy (ESEM), describing why ESEM is useful for characterising materials of interest in food research. It first surveys the main techniques of imaging and microanalysis in SEM. The principles of ESEM are then described, explaining how gases can be used to mitigate electrical charging of uncoated insulating materials and contribute to the image formation process, and other ways in which gases and specimen temperature control are useful for expanding the range of available techniques to yield additional information about the structure–property relations of hard, soft and even liquid specimens. Several key application techniques will be covered, from general imaging of dry or moist, uncoated specimens through to in situ dynamic experiments.

Key words

scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

environmental scanning electron microscopy (ESEM)

gases

aqueous and hydrated specimens

in situ

dynamic experiments

cryoESEM

1.1 Introduction

The main themes of this chapter are scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and its extension to environmental scanning electron microscopy (ESEM), with examples demonstrating the ways in which ESEM can be used for characterising materials of interest in food research. These materials range from confectionery and cereal products to fluid-filled vegetable cells and tissues through to emulsions, highlighting the diversity of material types that can be accommodated in the ESEM without the need for extensive specimen preparation traditionally associated with high vacuum electron microscopy.

Section 1.2 surveys the basic components of the SEM, the requirements for placing specimens in high vacuum and the main techniques of imaging and microanalysis. The principles of ESEM are then described in Section 1.3, explaining how gases can be used to mitigate electrical charging of uncoated, insulating materials and contribute to the image formation process. The section also explains other ways in which gases and specimen temperature control are useful for expanding the range of available techniques to yield additional information about the structure–property relationships of hard, soft and even liquid specimens. Several key application techniques are covered in Section 1.4, from general imaging of uncoated specimens, through to in situ dynamic experiments such as wetting and drying, mechanical testing and freezing. The chapter concludes with Section 1.5, briefly discussing the outlook for ESEM in the study of food microstructure.

1.2 Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

SEM has its beginnings in the 1930s (Knoll, 1935; von Ardenne, 1938a,b) and continued its development through the 1940s onwards (Zworykin et al., 1942; McMullen, 1953; Smith and Oatley, 1955; Everhart and Thornley, 1960), becoming commercially available in 1965. With it came the ability to study the microstructural characteristics of bulk materials with large depth of field across length scales ranging from millimetres to nanometres, offering a valuable new addition to the suite of visual characterisation tools such as light microscopy and scanning/transmission electron microscopy (S/TEM).

Typically, an SEM consists of an electron source to generate a beam of primary electrons; a column with electromagnetic lenses for focusing and demagnifying the primary electron beam; coils for scanning the electron beam across the specimen surface; a chamber containing a stage to hold the specimen; vacuum pumps to maintain the system under high vacuum (usually of the order of 10− 5–10− 7 Pa); and one or more detectors for collecting signals generated by electron irradiation of the specimen. Finally, the magnified image is displayed on a monitor, as the beam is scanned pixel-by-pixel across the field-of-view.

The most straightforward specimen types for SEM are metals, primarily since these materials are less prone to the effects of charging and damage under electron irradiation in high vacuum. Methods have evolved to address the issue of imaging electrically insulating materials such as polymers and ceramics, including coating the surface with conductive materials; incorporating heavy metal salts into the specimen to increase bulk conductivity, especially for biological materials; or using low voltages to minimise the accumulation of negative charge within the specimen, making it possible to image uncoated materials (Goldstein, 2003). For materials classes that are not naturally solids or have a tendency to outgas in vacuum, there are methods for conferring rigidity and preventing outgassing so that the specimen is suitable for high vacuum conditions in the SEM. These include critical point drying, freeze drying and the use of cryo-stages for frozen-hydrated specimens (cryoSEM).

Section 1.2.1 gives a brief overview of imaging in the SEM, mainly concentrating on beam-specimen interactions. For further reading on the topic as a whole, the interested reader is referred to Reimer (1985), Newbury et al. (1986), Sawyer and Grubb (1987), Goodhew et al. (2001) and Goldstein et al. (2003).

1.2.1 Beam–specimen interactions

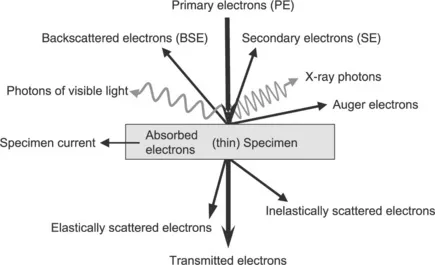

The SEM is primarily used for detecting backscattered electrons (BSEs) and secondary electrons (SEs), as well as X-rays and light, emanating from the surface or near-surface of bulk materials following interaction of the primary electron beam with the specimen. Specimen sizes are usually on the order of a few millimeters thick and can be up to around a centimeter in length or diameter, but the SEM can also be fitted with a detector to receive electrons transmitted through thin samples of up to a few microns in thickness, depending on the density of the specimen. To distinguish the latter technique from the more traditional ultra-high resolution scanning transmission electron microscope (STEM), this approach is often referred to as STEM-in-SEM. The principal signals in the SEM are illustrated in Fig. 1.1.

Fig. 1.1 Diagram showing a range of signals in the SEM. For bulk specimens, these include backscattered and secondary electrons, various photons such as X-rays and visible light and Auger electrons. For thin specimens, transmitted electrons provide information from the degree and nature of scattering.

BSEs are generated via elastic (non energy-absorbing) scattering of primary electrons within the specimen and are defined by convention as having energies from 50 eV all the way up to the primary electron energy of the source, which is usually in the range 1 to 30 keV. BSEs are thus essentially primary electrons that re-emerge from the specimen surface after a series of trajectory-altering interactions with the Coulombic field around atoms in the specimen. Inelastic energy loss mechanisms also come into play, causing electrons to transfer energy to the atoms of the specimen; hence BSEs are emitted from the surface with a range of energies (or are absorbed by the specimen). BSEs can travel from comparatively large depths (102–103 nm) to reach the surface, and the BSE emission co-efficient increases as a function of atomic number, so the BSE signal generally gives rise to images that reflect compositional information rather than being surface-sensitive.

SEs, of which there are several types, are produced via inelastic interactions with primary electrons. Here, the generated electrons (known as type I, or SEI) originate from the specimen’s atoms as primary electrons excite atomic orbital electrons sufficient to result in ionisation. SEs are defined as having energies up to 50 eV, but are typically emitted at around a few eV. Other types of SE include SEII, generated by BSEs as they exit the specimen surface and interact with atoms as they pass by, and SEII, generated by primary electrons striking the polepiece and chamber walls. The low-energy nature of SEs means that the signal is emitted from very close to the surface (< 50 nm) –SEs are prone to inelastic, energy-absorbing processes and so have a short escape depth – giving rise to images that are characteristically topographic, showing surface relief. SE imaging thus provides complementary information to the BS...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Contributor contact details

- Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition

- Dedication to Brian Hills

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part I: Microstructure and microscopy

- Part II: Measurement, analysis and modelling of food microstructures

- Appendix: Electron microscopy: principles and applications to food microstructures

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Food Microstructures by Vic Morris,Kathy Groves in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Food Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.