Introduction

The aesthetic of drinking beer is to an extent subliminal. The presentation of the beer in the glass in terms of its foam head, clarity/brilliance and color conjure Pavlovian anticipation for the perceptive drinker. There is no disputing the logic that “a beer drinker drinks as much with his or her eyes as with their mouth” (Bamforth et al., 1989). Other chapters in this book will offer insights into flavor, flavor stability, colloidal stability, color and the wholesomeness of beer.

That foam is perhaps one of the most appealing beer qualities is perhaps not surprising since the foam acts as an efficient gas exchange surface pitching aromas towards the drinkers olfactory sensors (Delvaux et al., 1995). As such, it provides a drinker’s first tantalizing entrée as to the quality of the beer’s flavor, freshness, refreshingness and wholesomeness. Foam is also tactile to the lips and impacts mouthfeel through its stability and its structure (bubble size). In part, this experience is modulated by the degassing of the beer in the mouth, which in turn is a function of beer carbonation/nitrogenation (Todd et al., 1996).

Some may counter, “most beer is drunk from a bottle.” Well, yes it is, and beer bottles are often attractive and convenient in their own right, although the drinker is largely missing out on the flavor cues extolled above. Bottles being glass are not opaque, particularly with the current fashion for clear and green varieties, so that they allow the drinker to clearly view foam formed as a result of the drinking action. In Belgium in particular, with branding of glassware, glass shape and material (Delvaux et al., 1995), the glass has become an art form that almost supplants the bottle. Lastly, in attempting to compare beer with wine, in at least more up market settings, it would certainly be considered to be passé or uncouth to drink wine from the bottle!

No brewer can afford to have their carefully crafted company or brand image downgraded by poor customer experiences. Given that the budget line for most brewers in the traditional beer countries is being expanded primarily by the provision of high margin premium beers, drinkers are perhaps more likely to pour the contents of the bottle in to a glass to savior the benefits outlined above. If not from direct experience, “alpha-beer drinkers” who do pour their beer into a glass or customers who have purchased their beer dispensed off tap (draught) may prejudice their colleagues’ brand perception based on perceived excellent or poor experiences. Thus insurance of an excellent experience for these influential drinkers and occasions is paramount in maintaining brand appeal.

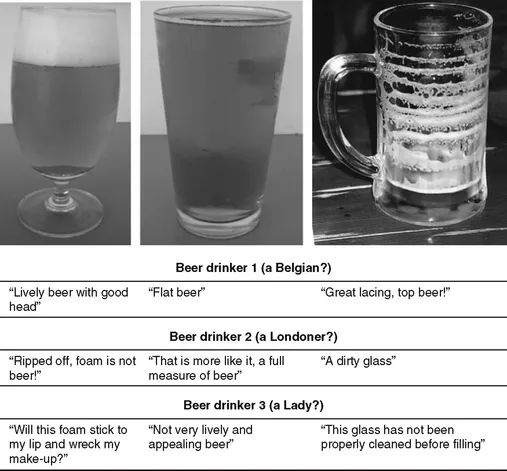

But what are the features of good foam quality? Typically, this is defined by a combination of its stability, quantity, lacing (glass adhesion or cling), whiteness, “creaminess” (small homo-disperse bubbles) and strength. Here “beauty” is definitely in the eye of the beholder as consumers discriminate between beers based on their foam characteristics. These choices have been found to diverge between genders, race or even region (Bamforth, 2000a; Smythe et al., 2002). Bamforth (2000a) concluded that “there is a divide between consumers who like to see stable (but not excessive) head or foam but a clean glass at the end of drinking and those who favour a lacing pattern on the glass.” More recently, it was demonstrated that men generally rate foam lacing higher than do women (Roza et al., 2006). In addition, a female colleague pointed out the “obvious.” Some women tend to be adverse to foam because the thought of its adherence to their lips is unsettling, in that it could spoil their carefully applied make-up. Overall, these quandaries can perhaps be simply outlined pictorially as shown in Figure 1.1.

It is the intention of this chapter to comprehensively appraise the science underpinning beer foam quality. The discussion will begin by considering the basics of foam physics and how these principles can be applied to the task of measuring foam quality then extend to the basic biochemical constituents such as protein species and hop acids that combined determine foam quality. This holistic understanding is aimed at providing brewers with the best possible knowledge so that they may manipulate the raw materials, process and options for delivery to consistently produce the optimal foam quality that their targeted customers demand.

Beer foam physics

Elementary to an understanding of beer foam quality are the principles of beer foam physics that underlie the interaction of the various beer components, dispense and finally customer presentation, be it in a glass or some other container. The principles concerned have been comprehensively described by Dr Albert Prins’ group of Wageningen (Prins and Marle, 1999; Prins, 1988; Ronteltap, 1989; Ronteltap et al., 1991), and by others such as Walstra (1989), Fisher et al. (1999) and Bamforth (2004a). These authors have simplified the somewhat complex physics involved into the following fundamental but interrelated events:

• Bubble formation and size

• Drainage

• Creaming (bubble rise or beading)

• Coalescence

• Disproportionation

Bubble formation and size

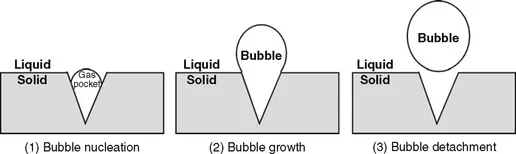

Despite beer being supersaturated with carbon dioxide, bubbles will not form spontaneously unless nucleation occurs (Figure 1.2), promoted by a particle, fiber or scratch in the glass (Prins and Marle, 1999) or the dispense mode, be that tap (Carroll, 1979) or bottle (Skands et al., 1999). These nucleation sites should ideally be small to create smaller bubbles that create foam that is most appealing to the drinker (Bamforth, 2004a). A desirable attribute of nitrogenated beers, due to the lower partial pressure of nitrogen gas compared to CO2, is the production of much smaller bubbles (Carroll, 1979; Fisher et al., 1999). Such principles are applied in the use of nucleated glassware such as the “headkeeper” style (Parish, 1997) or as a partial function of widgets (Brown, 1997; Browne, 1996) which will be discussed later in the chapter. Finally, the control of dispense angle and low dynamic surface tension leads to smaller bubbles with a homeodisperse size distribution, which results in the desirable “creamy” foam characteristic (Ronteltap et al., 1991).

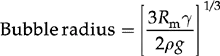

The factors governing the size of bubble that is generated in nucleation are described in the equation (1.1)

whereRm = radius of nucleation site (m)

γ = surface tension (mN m−1)

ρ = relative density of the beer (kg m−3)

g = acceleration due to gravity (9.8 m s−2)

The radius of the nucleation site is very significant, but surface tension and specific gravity (relative density) are less important.

Drainage

Upon its formation, foam is usually termed to be “wet.” The excess beer in the foa...