- 710 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Intermolecular and Surface Forces

About this book

This reference describes the role of various intermolecular and interparticle forces in determining the properties of simple systems such as gases, liquids and solids, with a special focus on more complex colloidal, polymeric and biological systems. The book provides a thorough foundation in theories and concepts of intermolecular forces, allowing researchers and students to recognize which forces are important in any particular system, as well as how to control these forces. This third edition is expanded into three sections and contains five new chapters over the previous edition.

- Starts from the basics and builds up to more complex systems

- Covers all aspects of intermolecular and interparticle forces both at the fundamental and applied levels

- Multidisciplinary approach: bringing together and unifying phenomena from different fields

- This new edition has an expanded Part III and new chapters on non-equilibrium (dynamic) interactions, and tribology (friction forces)

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Historical Perspective

1.1 The Four Forces of Nature

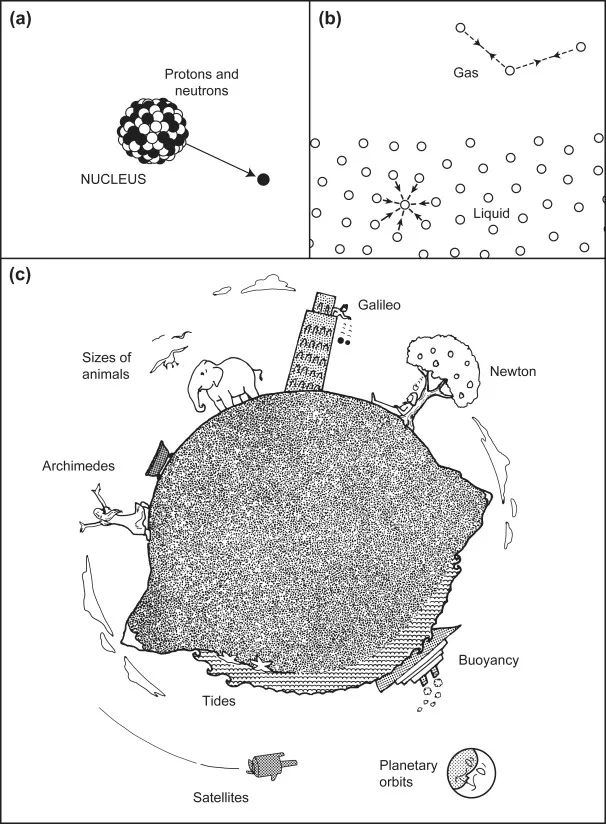

It is now well-established that there are four distinct forces in nature. Two of these are the strong and weak interactions that act between neutrons, protons, electrons, and other elementary particles. These two forces have a very short range of action, less than 10−5 nm, and belong to the domain of nuclear and high-energy physics. The other two forces are the electromagnetic and gravitational interactions that act between atoms and molecules (as well as between elementary particles). These forces are effective over a much larger range of distances, from subatomic to practically infinite distances, and are consequently the forces that govern the behavior of everyday things (Figure 1.1). For example, electromagnetic forces—the source of all intermolecular interactions—determine the properties of solids, liquids, and gases, the behavior of particles in solution, chemical reactions, and the organization of biological structures. Gravitational forces account for tidal motion and many cosmological phenomena, and when acting together with intermolecular forces, they determine such phenomena as the height that a liquid will rise in small capillaries and the maximum size that animals and trees can attain (Thompson, 1968).

Figure 1.1 The forces of nature. (a) Strong nuclear interactions hold protons and neutrons together in atomic nuclei. Weak interactions are involved in electron emission (β decay). (b) Electrostatic (intermolecular) forces determine the cohesive forces that hold atoms and molecules together in solids and liquids. (c) Gravitational forces affect tides, falling bodies, and satellites. Gravitational and intermolecular forces acting together determine the maximum possible sizes of buildings, mountains, trees, and animals.

This book is mainly concerned with intermolecular forces. Let us enter the subject by briefly reviewing its historical developments from the ancient Greeks to the present day.

1.2 Greek and Medieval Notions of Intermolecular Forces

The Greeks were the first to consider forces in a nonreligious way (see inset on the front cover and a brief explanation on the inside of the cover page). They found that they needed only two fundamental forces to account for all natural phenomena: Love and Hate. The first brought things together, while the second caused them to part. The idea was first proposed by Empedocles around 450 B.C., was much “improved” by Aristotle, and formed the basis of chemical theory for 2000 years.

The ancients appear to have been particularly inspired by certain mysterious forces, or influences, that sometimes appeared between various forms of matter (forces that we would now call magnetic or electrostatic). They were intrigued by the “action-at-a-distance” property displayed by these forces, as well as by gravitational forces, and they were moved to reflect upon their virtues. What they lacked in concrete experimental facts they more than made up for by the abundant resources of their imagination (Verschuur, 1993). Thus, magnetic forces could cure diseases, though they could also cause melancholy and thievery. Magnets could be used to find gold, and they were effective as love potions and for testing the chastity of women. Unfortunately, some magnetic substances lost their powers if rubbed with garlic (but they usually recovered when treated with goat’s blood). Electric phenomena were endowed with attributes no less spectacular, manifesting themselves as visible sparks in addition to a miscellany of attractive or repulsive influences that appeared when different bodies were rubbed together. All these wondrous practices, and much else, were enjoyed by our forebears until well into the seventeenth century and may be said to constitute the birth of our subject at the same time as alchemy, astrology, and the search for perpetual motion machines, which paved the way for chemistry and physics.

Still, notwithstanding the unscientific or prescientific nature of these practices, some important conceptual breakthroughs were made that deserve to be recognized. Ask any schoolboy or schoolgirl what the three most memorable scientific discoveries of antiquity are, and they will very likely mention Archimedes, Galileo, and Newton (see Figure 1.1). In each case, what happened (or is alleged to have happened) is well known, but what is less well known are the conceptual breakthroughs whose implications are with us today. Put into modern jargon, when Archimedes (287–212 B.C.) discovered Archimedes’ Principle, he had discovered that the force of gravity on a body can change—even its sign from attraction to repulsion—when it is placed in a medium that it displaces. Later we shall see that such displacement effects occur with many other types of interactions, such as van der Waals forces, with important consequences that in some cases have only recently been appreciated.

1.3 The Seventeenth Century: First Scientific Period

The notion of doing experiments to find out how nature works was an unknown concept until Galileo (1564–1642) demonstrated its power in his classic experiments on gravity, the motion of bodies, optics, astronomy, and proving the existence of a vacuum. In this he introduced the modern “scientific method” (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Scientists Who Made Major Contributions to Our Understanding of Intermolecular Forces (including some whose contribution was indirect)

But Galileo also introduced a new way of thinking that was not purely metaphysical. As an example, his experiment of throwing two different balls from the Tower of Pisa was conducted only after he had worked out the answer by applying a new form of reasoning—what we would today call “scaling arguments”—to Aristotelean Physics (see Problem 1.1), and his testing of his hypothesis by direct experiment was at the time also highly novel.1 This is also true of Newton’s discovery of the Law of Gravitation when an apple fell on his head. We must pause to think about how many previous heads, when struck by a falling apple, were prompted to generalize the phenomenon to other systems such as the orbit of the moon around the earth when acted on by the same force—a thought process that requires a leap of the imagination by a factor of 106 in time, 108 in distance, and 1024 in mass.

T...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Table of Contents

- Preface to the Third Edition

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Preface to the First Edition

- Units, Symbols, Useful Quantities and Relations

- Definitions and Glossary

- Chapter 1: Historical Perspective

- Chapter 2: Thermodynamic and Statistical Aspects of Intermolecular Forces

- Chapter 3: Strong Intermolecular Forces: Covalent and Coulomb Interactions

- Chapter 4: Interactions Involving Polar Molecules

- Chapter 5: Interactions Involving the Polarization of Molecules

- Chapter 6: Van der Waals Forces

- Chapter 7: Repulsive Steric Forces, Total Intermolecular Pair Potentials, and Liquid Structure

- Chapter 8: Special Interactions: Hydrogen-Bonding and Hydrophobic and Hydrophilic Interactions

- Chapter 9: Nonequilibrium and Time-Dependent Interactions

- Chapter 10: Unifying Concepts in Intermolecular and Interparticle Forces

- Chapter 11: Contrasts between Intermolecular, Interparticle, and Intersurface Forces

- Chapter 12: Force-Measuring Techniques

- Chapter 13: Van der Waals Forces between Particles and Surfaces

- Chapter 14: Electrostatic Forces between Surfaces in Liquids

- Chapter 15: Solvation, Structural, and Hydration Forces

- Chapter 16: Steric (Polymer-Mediated) and Thermal Fluctuation Forces

- Chapter 17: Adhesion and Wetting Phenomena

- Chapter 18: Friction and Lubrication Forces

- Chapter 19: Thermodynamic Principles of Self-Assembly

- Chapter 20: Soft and Biological Structures

- Chapter 21: Interactions of Biological Membranes and Structures

- Chapter 22: Dynamic Biointeractions

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Intermolecular and Surface Forces by Jacob N. Israelachvili in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Scienze biologiche & Biologia molecolare. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.