- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

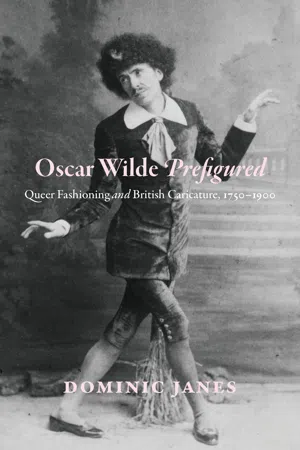

"I do not say you are it, but you look it, and you pose at it, which is just as bad," Lord Queensbury challenged Oscar Wilde in the courtroom—which erupted in laughter—accusing Wilde of posing as a sodomite. What was so terrible about posing as a sodomite, and why was Queensbury's horror greeted with such amusement? In Oscar Wilde Prefigured, Dominic Janes suggests that what divided the two sides in this case was not so much the question of whether Wilde was or was not a sodomite, but whether or not it mattered that people could appear to be sodomites. For many, intimations of sodomy were simply a part of the amusing spectacle of sophisticated life.

Oscar Wilde Prefigured is a study of the prehistory of this "queer moment" in 1895. Janes explores the complex ways in which men who desired sex with men in Britain had expressed such interests through clothing, style, and deportment since the mid-eighteenth century. He supplements the well-established narrative of the inscription of sodomitical acts into a homosexual label and identity at the end of the nineteenth century by teasing out the means by which same-sex desires could be signaled through visual display in Georgian and Victorian Britain. Wilde, it turns out, is not the starting point for public queer figuration. He is the pivot by which Georgian figures and twentieth-century camp stereotypes meet. Drawing on the mutually reinforcing phenomena of dandyism and caricature of alleged effeminates, Janes examines a wide range of images drawn from theater, fashion, and the popular press to reveal new dimensions of identity politics, gender performance, and queer culture.

Oscar Wilde Prefigured is a study of the prehistory of this "queer moment" in 1895. Janes explores the complex ways in which men who desired sex with men in Britain had expressed such interests through clothing, style, and deportment since the mid-eighteenth century. He supplements the well-established narrative of the inscription of sodomitical acts into a homosexual label and identity at the end of the nineteenth century by teasing out the means by which same-sex desires could be signaled through visual display in Georgian and Victorian Britain. Wilde, it turns out, is not the starting point for public queer figuration. He is the pivot by which Georgian figures and twentieth-century camp stereotypes meet. Drawing on the mutually reinforcing phenomena of dandyism and caricature of alleged effeminates, Janes examines a wide range of images drawn from theater, fashion, and the popular press to reveal new dimensions of identity politics, gender performance, and queer culture.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Oscar Wilde Prefigured by Dominic Janes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Geschichte & Britische Geschichte. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

WILDE: . . . I then said to him, “Lord Queensberry do you seriously accuse your son and me of sodomy?” He said, “I do not say that you are it, but you look it (laughter)—

JUDGE: I shall have the Court cleared if I hear the slightest disturbance again.

WILDE: —but you look it and you pose as it, which is just as bad.”1

Laughter filled the room when Lord Queensberry’s verbal challenge to Oscar Wilde in June 1894 was related in court. The issue of the truth of poses was of importance in the libel trial of 1895 because the scrawled words on the card left by John Sholto Douglas, the Marquess of Queensberry, at the Albemarle Club were read as an accusation that Wilde had posed as a sodomite and, therefore, was one. What was so terrible to Queensberry about posing as a sodomite, and why was Wilde’s account of his antagonist’s disgust greeted with amusement in the courtroom? I will suggest that what divided the two sides in this case was not so much the question of whether Wilde was or was not a sodomite but whether it did or did not matter that people could appear to be sodomites. On the one hand, it could be held that sodomy was so disgusting and obscene that it should be kept, at all costs, from public attention. On the other, it might be felt that intimations of sodomy were simply part of the amusing spectacle of sophisticated life. From the latter viewpoint, men who sought sex with other men could deploy coded expressions of their desires that were more or less obvious and legible depending on the audience at which they were targeted. Pleasure was facilitated by flirtatious visual games of posing and supposing in opposition to textual imperatives of naming and shaming. However, to flirt with the appearance of sodomy was not the same as proud affirmation, since it had to take place in the context of the threat of public denunciation. Moreover, to pose as a sodomite was to engage with forms that had developed in collusion with imagery conjured from the lurid imaginations of moral opponents.

This book reads queer performances and phobic caricatures as interrelated phenomena, understanding the word “queer” to refer to transgressions of normative constructions of gender and sexuality that focus on aspects of male same-sex desire.2 There is no single definition of the term “queer” as used in academic writing, but it is generally employed in the exploration of circumstances in which there is some form of overlap between the cultural politics of transgression and the construction of alternatives to normative sexual identities. Because queerness is, therefore, generally understood to exist in relation to the transgression of categories, it necessarily does more work than the terms “homosexual” or “gay.” The main problem with these latter words is that they are largely defined negatively in relation to the notion of “not being sexually straight” and operate through the assertion of a new oppositional category, whereas “queer” can be seen as that which sets itself up against the normative, whatever that might be, including against the imperative to categorize.3 This study looks, in particular, beyond the notion of the trials of Oscar Wilde in 1895 as representing a “queer moment” in the course of which sodomitical acts become joined to the novel creation of a homosexual identity.4 Wilde’s image, I will argue, was prefigured in a ribald, satirical tradition since the eighteenth century, which associated dandified performances with sodomitical desires.

Alan Sinfield’s The Wilde Century: Effeminacy, Oscar Wilde and the Queer Moment (1994) remains an important study, but it should be placed in context as a product of an academic environment in which much of emergent queer theory was focused on textual concerns. It was widely accepted that it was through language that homosexuality was constructed in the course of the later nineteenth century. This had a number of repercussions. It meant that far more attention was paid to Wilde’s literary production than to his visual and performative self-fashioning.5 And it also resulted in an understanding of his material form as strangely inert matter onto which meaning was written, as can be seen from Moe Meyer’s view of the events of 1895: “If we read Wilde’s containing inscription into discourse and his physical containment behind bars as the successful culmination of his efforts to construct a personal homosexual identity, then a solution to one of history’s most perplexing psycho-mysteries can be offered. . . . [Instead of fleeing,] he simply waited for the State to begin its inscriptory process. . . . Wilde needed the State’s dominance, with its control over signification, in order to complete the project by linking his transgressive reinscription of bourgeois masculinity to sexology’s homosexual type.”6

However, if equal attention is paid to Wilde’s visual and material, as well as to his textual, performances, it becomes apparent that he was visibly legible to some people as a sodomitical type of person before his trials. The year 1895 did not see the immediate creation of a homosexual identity but rather the distribution of an image of the effeminate pervert that was to become a dominant stereotype of the homosexual for much of the twentieth century.7

A further concern of 1990s scholarship was identity politics, yet same-sex desire must take place through sensory admiration before it can become the basis for an identity. Edmund White drew attention to the centrality of looking in his States of Desire: Travels in Gay America (1980). To White, the visual admiration of others’ bodies was a product of busy urban life. “What I am singling out,” he wrote with reference to New York, “are the scanning eyes that lock for an instant, the cool and thorough appraisals of someone’s person and apparel—the staring in a word . . . the staring is continuous, a civic habit.”8 It was, I would argue, in association with the experience of admiring and being admired that identities based on sexual desires began to develop. Visual codes then started to appear with the aim of attracting the attention of others with similar tastes. In due course, some of these performances, particularly those that played with tropes of effeminacy, were noticed and written up by sexologists and other social commentators as part of the truth of the homosexual. But it was in the nature of such visual and material performances that, save for the most blatant, they tended to hint at rather than openly express same-sex desires. The challenge today of correctly interpreting such acts of self-fashioning is all the greater because often they have only been preserved for us through references in other (often hostile) media. In this study, I focus on visual caricature because it was a genre predicated on exaggeration. The nuanced codes with which dissident desires were signaled in the street appear in more pronounced forms in satirical productions. Not only does this enable lost visual discourses to be recovered, but it also does so in a way that acknowledges the power of mockery in creating such queer signs in the first place. Satirists, I will argue, were frequently implicated in the scenes that they affected to denounce, since, like the mirrors that were installed in eighteenth-century theaters, humorous prints reflected the foibles of fashionable society. Caricaturists needed to be intimately familiar with that which they chose to mock, and their productions frequently acted to spread awareness of the queer possibilities of performance.9 I aim to supplement the well-established narrative of the inscription of sodomitical acts into a textually constructed homosexual label and identity at the end of the nineteenth century by teasing out the means by which same-sex desires could be signaled through visual display in Georgian and Victorian Britain.

The central focus of this study is the fashionably clothed male body and its representation in caricature. This focus requires attention to be moved on from some of the more familiar textual evidence for the history of same-sex desire (such as legal sources) but also demands that a visual culture approach be brought to bear on materials, such as satirical prints, that have not always been given a prominent place in art history studies.10 This strategy also relies on recognizing that these satirical materials could be interpreted differently according to who was viewing them. Thus, rather than seeking to demonstrate that caricature of excessive male fashion did or did not refer to effeminacy rather than sexual desire, my aim is to explore whether such works could have been viewed as bearing sexual significance. This involves a parallel approach to that taken by Oliver S. Buckton in his study Secret Selves: Confession and Same-Sex Desire in Victorian Autobiography (1998). The queerness of the texts that he was exploring, and of the images that I will be discussing, lies substantially in the ways in which sexual revelations were negotiated in the context of various degrees of self-awareness and coded expression.11 The story that I will be telling is not one in which it took a literary genius in collision with the disciplinary power of the state to conceptualize previously inchoate yearnings but rather one in which people referenced and learned from each other. This involved a combination of hostile and sympathetic visual messages, since satirists and the satirized influenced each other and sometimes were the self-same people.

Queer visual self-expression, seen from this perspective, was an art of looking, copying, and exaggeration in which prefiguration played as vital a role as originality. The geographical focus of this creative activity was the crowded heart of the metropolis of London and particularly the West End.12 The study of fashion and clothing history, as well as wider practices of visual self-fashioning, has advanced rapidly over the last couple of decades. Christopher Breward made a particularly significant contribution in a series of studies including The Culture of Fashion: A New History of Fashionable Dress (1995) and Fashioning London: Clothing and the Modern Metropolis (2004). Breward has, among many other things, developed a nuanced understanding of the tendencies toward the containment of formerly elaborate male self-presentation in the course of the eighteenth century. In the 1930s, psychologist J. C. Flügel labeled this process as the “great masculine renunciation.”13 In the course of this process, the formal French-style court dress, the habit habillé, was superseded by simpler garments that are the ancestors of the modern three-piece suit.14

The fact that fashionable men’s clothing during this period became cheaper and plainer had a number of effects. First, the precise fit of the clothes became increasingly significant, and this had the effect of highlighting the vitality, or otherwise, of the body beneath the clothes.15 Second, the wearing of elaborate silk costumes by men was increasingly associated with tastes that were financially profligate and unpatriotic. Third, such attire was increasingly read as effeminate, since it used colors and materials that were mostly employed by women. Fourth, the wearing of fashionable clothing spread further down the social spectrum, creating anxiety about the fragility of social status. It was in these circumstances that the word “dandy” was first coined in the 1780s to indicate vulgar and awkward social upstarts.16 Male fashionability from this point onward depended on the mastery of increasingly subtle visual codes that mediated between ostentation and restraint.17 Dandyism came to be associated with claims to personal autonomy set against the backdrop of a conformist set of assumptions about style.18 It was an art that displayed virtuosity, as Kaplan and Stowell have said of Wilde’s stage comedies, “by working within limitations.”19 In such circumstances, the judicious application of satirical wit could temporarily relieve the anxieties of a society that had become preoccupied with the correct performance of manliness because it was, arguably, increasingly insecure about the essential nature of masculinity.20 Witty self-presentation that played with stereotypes had the potential to offer the dandy a place of social prominence in which at least some of his personal foibles might be condoned.21 The performativity of both gender and class involved in such practices was tacitly acknowledged both in the theater of everyday life and on the stage itself. Victorian dandyism, as was the case with its Georgian precursors, was widely treated in theater performances that ranged from Wilde’s social comedies to the more raucous music hall travesties in which charming ladies presented themselves in the guise of the young buck about town.

In some of his most detailed work on this topic, published as part of The Hidden Consumer: Masculinities, Fashion and City Life 1860–1914 (1999), Christopher Breward argues for strong continuities of male fashioning through and beyond the nineteenth century. After Wilde’s imprisonment, he writes, “the musculature of the strong man and the monocle of the male impersonator continued to delineate the boundaries of a key public discourse on the nature of modern masculinities and consumption dating back to the era of dandy insurrection in the 1830s and 1840s.”22 Moreover, he says that dandyism should be understood as a reaction not merely to desires for self-fashioning in general but also to the existence of a “competitive sexual market place.”23 And yet he follows Sinfield’s reasoning when he says that although “the new figure of the homosexual . . . reflected previous anxieties regarding the connections between gender, class and consumption . . . no single material template for homosexuality existed outside of the complex and secretive subcultural groupings that had constituted London’s demi-monde since the late seventeenth century.”24 Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick argued that “by 1865, a distinct homosexual role and culture seem already to have been in existence in England for several centuries,” which she saw as “at once courtly and in touch with the criminal.” Yet she saw this milieu as highly secretive, such that “there seems in the nineteenth century not to have been an association of a particular personal style with the genital activities now thought of as ‘homosexual’ . . . the educated middle classes . . . operated sexually in what seems to have been startlingly close to a cognitive vacuum.”25 I will be arguing that such reasoning underplays the degree of knowledge available concerning the possibilities of same-sex eroticism in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Sedgwick’s thinking on this point misses the possibilities of queer modulations of style through its expectation that a single “homosexual” appearance was notable by its absence. Breward, by contrast, does suggest that such a template existed but that either it is lost to us or it was not of great significance because it was restricted to the “demi-monde.” As I will argue, queer...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- 1. Introduction

- Part One: “Dammee Sammy you’r a sweet pretty creature”

- Part Two: “Corps de beaux”

- Part Three: “An unspeakable of the Oscar Wilde sort”

- References

- Index

- Endnotes