eBook - ePub

The War in American Culture

Society and Consciousness during World War II

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The War in American Culture

Society and Consciousness during World War II

About this book

The War in American Culture explores the role of World War II in the transformation of American social, cultural, and political life.

World War II posed a crisis for American culture: to defeat the enemy, Americans had to unite across the class, racial and ethnic boundaries that had long divided them. Exploring government censorship of war photography, the revision of immigration laws, Hollywood moviemaking, swing music, and popular magazines, these essays reveal the creation of a new national identity that was pluralistic, but also controlled and sanitized. Concentrating on the home front and the impact of the war on the lives of ordinary Americans, the contributors give us a rich portrayal of family life, sexuality, cultural images, and working-class life in addition to detailed consideration of African Americans, Latinos, and women who lived through the unsettling and rapidly altered circumstances of wartime America.

World War II posed a crisis for American culture: to defeat the enemy, Americans had to unite across the class, racial and ethnic boundaries that had long divided them. Exploring government censorship of war photography, the revision of immigration laws, Hollywood moviemaking, swing music, and popular magazines, these essays reveal the creation of a new national identity that was pluralistic, but also controlled and sanitized. Concentrating on the home front and the impact of the war on the lives of ordinary Americans, the contributors give us a rich portrayal of family life, sexuality, cultural images, and working-class life in addition to detailed consideration of African Americans, Latinos, and women who lived through the unsettling and rapidly altered circumstances of wartime America.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2014Print ISBN

9780226215129, 9780226215112eBook ISBN

9780226215105PART 1

The Quest for National Unity

ONE

No Time for Privacy: World War II and Chicago’s Families

Perry R. Duis

During World War II, Mrs. Frances Jankowski rose at 4:45 A.M. six mornings each week. After feeding her family and riding a streetcar to the Swift and Company stockyards plant, she spent the next eight hours trimming pork scraps for sausage. After the ride back to her South Rockwell Street home, she did the family shopping, cleaned their six-room apartment, cooked dinner, and still found time to cultivate a victory garden of two thousand square feet, collect scrap, and participate in neighborhood civil defense exercises. On Sundays she did the washing and ironing. Her husband John had spent the day as an elevator operator, the only job he could hold because of a decade-long illness. Together the Jankowskis invested 15 percent of their family income in war bonds to hasten the safe return of three sons and a daughter who were in military service.1

The Chicago Tribune lauded the Jankowski family as an ideal home front household, but their hectic domestic schedule was far from unique. During World War II families all over Chicago and America balanced extended working hours plus scrap drives, civil defense exercises, victory gardens, neighborhood ceremonies honoring those entering the service, and countless other demands made on the time of good citizens. All of these endeavors were encouraged by official propaganda claiming that military success abroad depended on home front support, requiring citizens to sacrifice domestic comforts and conveniences in exchange for the protection of the American family.2 What the federal government implied but did not openly say was that victory overseas required an unprecedented invasion of home front duties into the private lives of its citizens.

The routes and methods of this domestic invasion grew out of the urbanization that produced a complex system of interdependencies. Those who lived in cities relied on someone else for almost everything needed to operate their households, and this gave the federal government its most effective means of enlisting civilian support for the war effort among city dwellers, whose concentration made them most vulnerable to enemy attack.3 Home front programs had far less impact on rural America, where families were much more self-sufficient for everyday necessities. At the same time, much farm labor was exempt from the military draft, and there was no real need for extensive civil defense programs except where the farmsteads were close to cities.4

The penetration of urban domestic life also depended on manipulating peoples sense of time. The war seemed to accelerate the pace of life. Even by today’s standards, the speed with which things were organized and built during World War II remains impressive.5 This hurried-up world of patriotic production outside the home altered the lives of those within it. Whereas farm life continued to be controlled largely by the seasons and peoples internal clocks, cities had always been governed by signals and schedules that were more public and social. The factory whistle, the school bell, the public clock, the commuter train timetable, and the signals that opened the doors of downtown stores and offices controlled the schedules of adults and children. Each rush hour was a public accounting of the transitions between different phases of the workdays of hundreds of thousands of Chicagoans.6 The disruption of these rhythms of everyday life greatly altered the private world.

Prewar Patterns of Time and Privacy

During the half century before 1941, the uses of domestic space and time in Chicago and elsewhere already had undergone changes that would shape the patterns of home front participation. The prewar years had witnessed a growing fascination with the efficiency movement launched by Frederick Taylor to reduce the waste of time. Timesaving schemes marked the new quest for “scientific management” in the operation of factories, stores, and offices, while early expressways like Chicago’s Lake Shore Drive and faster speeds for public transit were supposed to reduce the time spent traveling between work and home.7

Meanwhile, at the other end of the commuters journey, the traditional view held that families functioned most effectively when they could build social barriers around themselves. Supposedly, privacy allowed the family to be a sheltering institution. A backyard kept young ones off the street; a piano in the parlor and books to read obviated the need for commercial amusements. Privacy also permitted personal modesty: a family needed its own bathing and toilet facilities, and children of different genders needed separate bedrooms.8

Traditionally, income had been the primary determinant of how much privacy and space a family could attain. The poorest Chicagoans had always lived on the street or in other public places, in full public view. A trickle of income put a family into a crowded tenement, where at least they were behind walls part of the time. Additional income might bring a modest cottage on a small lot, and greater wealth bought more space that was also functionally specialized.9

This traditional goal of insularity for the household, and its relation to wealth, had begun to erode well before World War II. New household appliances were supposed to free housewives’ daytime hours for other pursuits, many of them outside the home.10 Department store shopping and commercial amusements, for instance, drew middle- and upper-class people out of their private worlds. On the other hand, the automobile gave even working-class families a measure of privacy from crowded mass transit and independence from its schedules in their pursuit of leisure or on the commute to work. Further, as consumer goods came within their reach, working-class families still made the ultimate decisions about what radio programs and Victrola records they would hear, if any, what newspapers and magazines entered their homes, and what prepared foods were found on their tables.11

No development, however, disrupted the traditional idea of proper privacy as much as the Great Depression, with its devastating impact on families. Accounts of the suffering of the 1930s often include descriptions of the way middle-class people tried to hide their plight. The trip to the welfare agency, being seen on a WPA work crew, the public humiliation of eviction—all these sad events represented not only a loss of status and pride, but also a loss of privacy. Adult children and parents, as well as other extended family members, moved in together. Although the arms buildup of the late 1930s began a return to prosperity, Pearl Harbor occurred before many of these effects of the depression could be healed. The decade of suffering, in essence, had helped soften the walls of privacy and, to a substantial extent, made it that much easier for the home front programs to penetrate the privacy of the family.12

Fear and Enthusiasm, 1941–43

Although America had been moving toward involvement in world war for at least two years, the attack on Pearl Harbor constituted a sudden invasion of the American consciousness that enabled other intrusions into domestic life. During the first months of the war, most home front projects in Chicago were met with nervous enthusiasm prompted by a general belief that the city might be bombed. The entire civil defense program, with its responsibilities shared by as many people as possible, required at least a minimum of fear to guarantee participation. For most families, involvement also became an adventure, a way every citizen could feel he or she was making an important contribution to the war effort. Families learned not only how to use twenty-four-hour “military time,” but also how to calculate local time in distant parts of the world where loved ones might be serving.13

This atmosphere of involvement, in turn, helped generate a willingness to compromise family privacy for the patriotic good. Collecting salvage to be recycled into war goods required an especially complete intrusion into the home. Advertising, posters, radio, and neighbors exhorted housewives to collect kitchen grease for conversion into nitroglycerine, search cupboards and attics for unused aluminum cooking utensils and other metal junk, and bundle newspapers and magazines to be reprocessed into shipping containers for war goods. Their husbands pulled old tires and discarded iron and steel items from basements and garages, while youngsters scoured alleys, vacant lots, and other play places for anything salvageable. The private satisfaction of helping often was subordinated to organized scrap drives that became a form of team sport, with neighborhoods and assorted organizations vying to collect the most.14

Civil defense exercises were an invasion of privacy that was welcomed by Chicagoans who feared enemy attack. Not only were families asked to give up some of their spare time to attend meetings and study the official literature, but the local civil defense program fingerprinted as many as 100,000 Chicago volunteers and investigated their backgrounds.15 Some training exercises, especially blackouts, directly altered life at home. To block all light that might be seen from outside, homemakers had to take time either to find cloth and make blackout curtains or to buy them. These curtains were to be put in place for every test, and even then residents were asked to turn off their radios because the tubes glowed and to avoid smoking lest the light be visible around the edges.16

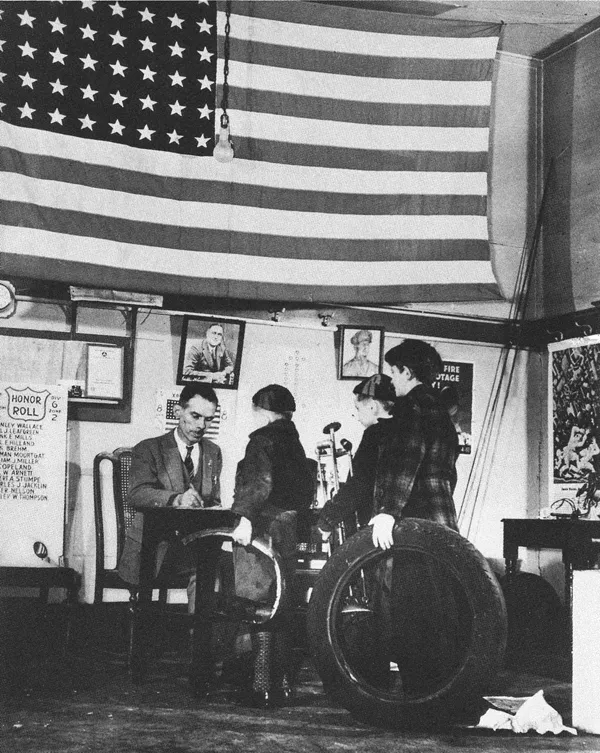

Figure 1.1. Children bringing in scrap to a civil defense office in Chicago, 1942. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Figure 1.2. Chicago area family hears war news, 1942. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Meanwhile, one of the duties of the civil defense block captain was to gather information about everyone in the jurisdiction. In an attack it would be vital to know something about the layout of each dwelling, when a family might be home, where its members worked, and other details. Knowing about the neighbors also enhanced the block captain’s security function of reporting draft dodgers and suspicious characters who might be spies. Training sessions early in 1942 schooled block captains in the techniques of keeping card files on neighbors and getting the necessary information without seeming nosy or pushy.17

Finally, compliance with the ideals of home front unity sometimes required public forms of patriotic behavior to demonstrate one’s private loyalty. Defying the city ordinance against ragweed might mean a householder did not care about the efficiency of defense workers who had hay fever. Colorful window stickers and posters told neighbors that a family bought bonds, contributed to scrap drives, planted victory gardens, and had someone serving in the armed forces. Failing to advertise one’s loyalty might arouse suspicion of being a “mattress stuffer”—hoarding money instead of buying bonds—or worse.18

War and the Private Family, 1941–43

The war affected every aspect of domestic life in Chicago, including family formation. After Pearl Harbor, couples flooded the Cook County marriage license bureau at more than twice the usual rate. Many chose mass-produced weddings that were sold as a package by downtown department stores and hurried through by churches or local judges. There was no time for even the longest-standing family traditions, such as using an heirloom ring or exchanging gifts, and the honeymoon sometimes consisted of a few nights in a Loop hotel before reporting to duty.19

For thousands of war brides, this rush of events was followed by months, even years, of delay before they could establish a household. Not only were these times marked by worry and long lapses of communication, but there was also a substantial loss of privacy. Letter writers were pressured to use V-mail, a compact format that was reduced to microfilm to save precious space in overseas shipments, then printed photographically for the recipient. V-mail also helped military censors obliterate any information that might tell where military personnel were or were going. Packages from home were inspected so thoroughly that by late 1942 platoon commanders were, in effect, dictating what families could and could not send as holiday gifts.20

At home new brides often lost spatial privacy. Lacking money and unable to make firm domestic plans, many newly formed “households” consisted of what could fit in a few suitcases or trunks. War brides often moved back home with their parents or lived in a succession of rooming houses. Many military wives also joined one of the dozens of support groups that started during the holiday season of 1941 and found themselves revealing their most intimate fears to people who had been strangers only a few weeks earlier. One war bride confided to a University of Chicago graduate student, “Before our separation, we talked quite frankly (albeit sadly) of the possibility of extra-marital relations. We both felt unsure about this; we really could not decide whether it would be condoned in our consciousnesses. But the important point here is that we did not blind ourselves to its likelihood.”21

Many women also were advised to lose their worries outside the home by plunging into volunteer programs like Bundles for Blue Jackets, Red Cross, and dozens of other war-related charities. Even such traditional tasks as knitting or baking cakes and pies took on new significance if the products made their way to soldiers and sailors. Besides the private satisfaction of helping, there was informal pressure to contribute more baked goods than other neighborhoods to the Chicago Service Men’s Centers and similar organizations.22

By March 1942 a grim realization had set in that the war would change the way everyone lived, regardless of social class. Early Allied defeats foretold a long conflict that could be shortened only by the total commitment of every individual.23 This grim need-to-win attitude coincided with disappearing supplies of consumer goods and the depletion of private stocks of rationed items. The intrusion of wartime was accelerated by the complex interdependencies of urban life. Unlike rural people, city dwellers grew very little of their own food. Home refrigerators were inefficient, with tiny freezers, and because preservatives and individual packaging were little used, many foods had a short shelf life. The most effective way to slow down the buy-and-consume cycle was through ca...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part One. The Quest for National Unity

- Part Two. Interpreting the “American Way”

- Part Three. The Challenge of Race and Resistance to Change

- Part Four. Mobilization for Change

- Part Five. The New Political Paradigm

- List of Contributors

- Notes

- Name Index

- Title Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The War in American Culture by Lewis A. Erenberg, Susan E. Hirsch, Lewis A. Erenberg,Susan E. Hirsch in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.