- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

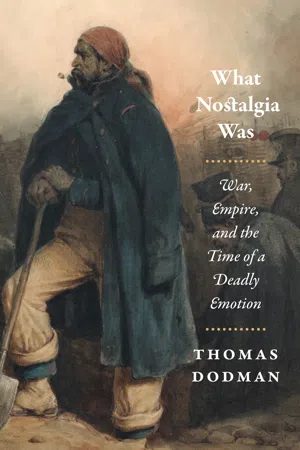

Nostalgia today is seen as essentially benign, a wistful longing for the past. This wasn't always the case, however: from the late seventeenth century through the end of the nineteenth, nostalgia denoted a form of homesickness so extreme that it could sometimes be deadly.

What Nostalgia Was unearths that history. Thomas Dodman begins his story in Basel, where a nineteen-year-old medical student invented the new diagnosis, modeled on prevailing notions of melancholy. From there, Dodman traces its spread through the European republic of letters and into Napoleon's armies, as French soldiers far from home were diagnosed and treated for the disease. Nostalgia then gradually transformed from a medical term to a more expansive cultural concept, one that encompassed Romantic notions of the aesthetic pleasure of suffering. But the decisive shift toward its contemporary meaning occurred in the colonies, where Frenchmen worried about racial and cultural mixing came to view moderate homesickness as salutary. An afterword reflects on how the history of nostalgia can help us understand the transformations of the modern world, rounding out a surprising, fascinating tour through the history of a durable idea.

What Nostalgia Was unearths that history. Thomas Dodman begins his story in Basel, where a nineteen-year-old medical student invented the new diagnosis, modeled on prevailing notions of melancholy. From there, Dodman traces its spread through the European republic of letters and into Napoleon's armies, as French soldiers far from home were diagnosed and treated for the disease. Nostalgia then gradually transformed from a medical term to a more expansive cultural concept, one that encompassed Romantic notions of the aesthetic pleasure of suffering. But the decisive shift toward its contemporary meaning occurred in the colonies, where Frenchmen worried about racial and cultural mixing came to view moderate homesickness as salutary. An afterword reflects on how the history of nostalgia can help us understand the transformations of the modern world, rounding out a surprising, fascinating tour through the history of a durable idea.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access What Nostalgia Was by Thomas Dodman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 19th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2018Print ISBN

9780226492940, 9780226492803eBook ISBN

9780226493138Chapter 1

Nostalgia in 1688

Home is where one starts from.

T. S. ELIOT, East Coker (1940)

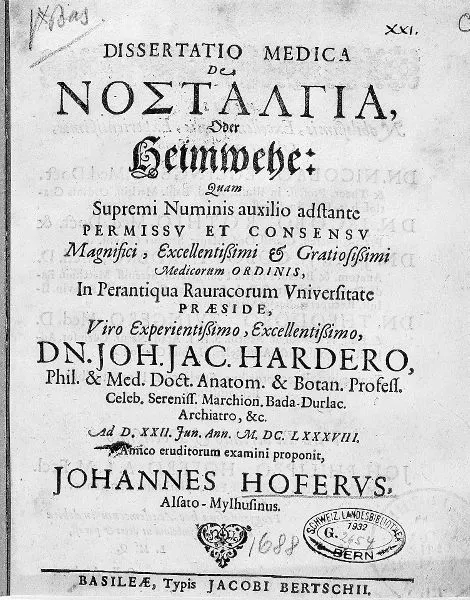

Johannes Hofer’s 1688 Dissertatio medica de nostalgia, oder Heimwehe was perhaps destined to never feature in medical history textbooks. This was, after all, but the work of a medical student who chose to write on a disease no one had then heard of, and that we would be hard pressed to find in any medical taxonomy today. An unlikely medical maverick, Hofer cannot be credited with any lasting contribution to the Western medical tradition, despite serving the profession diligently throughout his life as a general practitioner in his hometown of Mulhouse. Nevertheless, he did bequeath to posterity a term that has, for better or worse, become second nature to modern life—almost a “keyword” in its own right, but one with a little-known medical genesis. The quest to understand where our modern infatuation with nostalgia comes from must therefore begin with the term’s unlikely inventor and the clinical hypotheses of a nineteen-year-old.

As Jean Starobinski remarks, by providing a scientific name for and full clinical description of what had hitherto been a vernacular category, Hofer transformed “an emotional phenomenon [Heimweh] into a medical phenomenon [nostalgia].”1 Why he did so, and what this says about the time in which he lived, are the questions this chapter seeks to elucidate. Briefly put, my argument is twofold: that seventeenth-century clinical breakthroughs and evolving medical theories enabled Hofer to conceive of nostalgia in a way that closely resembled contemporary understandings of melancholia and other emotional disorders; but that medical transformations alone cannot account for the perceived need to devise a new diagnostic category (rather than use an existing one). As a detailed exegesis of Hofer’s remarkable text reveals, the making of nostalgia did not proceed directly from an epidemiological revolution or one of the many discoveries that overhauled Western medicine in the age of scientific revolution. Rather, to grasp its conditions of possibility we must cast our net further afield, beyond medicine itself, to the broader social, political, and intellectual forces that shaped Hofer’s life and that of his contemporaries. Nostalgia, it turns out, was born of a time of conflict and generalized instability, a “General Crisis” that rocked much of Europe—and the upper Rhineland in particular—throughout the seventeenth century.

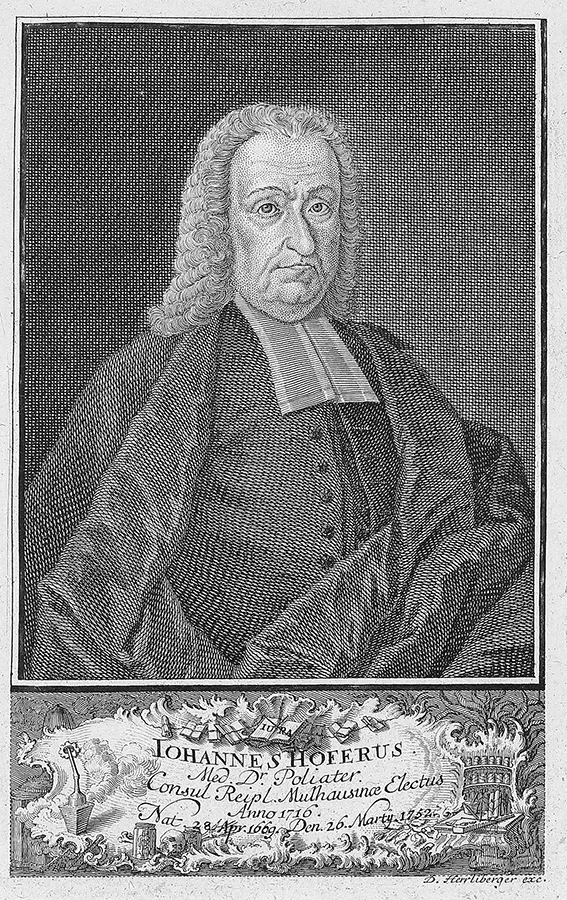

Figure 1.1. Johannes Hofer (1669–1752) pictured in 1716, as Poliater (junior town physician) and elected consul of the Republic of Mulhouse. Portrait by David Herrliberger, from his Schweitzerischer Ehrentempel, in welchem die wahren Bildnisse teils verstorbener, teils annoch lebender berühmter Männer (Basel, 1748–58). Courtesy of the Schweizerische Nationalbibliothek, Bern.

Figure 1.2. Title page from Johannes Hofer’s Dissertatio medica de nostalgia, oder Heimwehe (Basel: Jacob Bertsch, 1688). Courtesy of the Schweizerische Nationalbibliothek, Bern.

An Unlikely Medical Maverick

Johannes Hofer was born in the Alsatian town of Mulhouse on May 2, 1669, the last of twelve siblings in a prosperous family of prominent local pastors. We know little of his childhood, other than the fact of his father’s premature death when Johannes was only six years old. It certainly was stern and studious in keeping with Mulhouse’s official Calvinist piety. Most likely, it also taught the young man the proud history of his hometown, an independent and staunchly republican enclave within the Holy Roman Empire since the fourteenth century. Hofer would already have been well versed in humanist, moral, and civic traditions when, barely a teenager, he followed his ancestors’ footsteps to continue his studies in the neighboring town of Basel, home to the first Swiss university. He read philosophy and theology for three years and, in 1685, opted to heal bodies rather than souls by enrolling in medical school.2 As it turned out, he would end up curing both.

Established by papal bull in 1459, the University of Basel emerged out of the wars of religion as a leading institution of higher education in Protestant Europe, attracting students from nearby Rhineland and German states. Its medical faculty courted controversy in 1527 when Paracelsus famously burned Avicenna’s Medical Canon (the main reference work of medieval medicine), but thereafter became a reputable center for learning, book printing, and the liberal humanism typical of reformed cities. For much of the seventeenth century, the dominant natural philosophy taught in Basel was an eclectic synthesis of Aristotelianism and Ramism, the iconoclastic body of thought developed by the Huguenot Petrus Ramus (who also lectured at the university before being murdered during the St. Bartholomew’s day massacre). Medieval scholasticism was therefore already on the defensive when Cartesianism was introduced into the classrooms in the 1660s, prompting a major curricular reorientation toward empiricism and new chemical and physical explanatory models.3

When Hofer matriculated in 1685, he therefore entered an institution and a larger medical profession undergoing unprecedented transformations. He found close mentors in two junior professors, both graduates of the medical school: Jacob Harder, who taught rhetoric and physics before claiming the chair of anatomy and botany in 1687 (the lowest of three full professorships, after those of medical theory and medical practice); and Theodor Zwinger, the scion of an important family of doctors from Basel, who held the chair of eloquence during Hofer’s studies, before also moving on to the chairs of anatomy and practical medicine thereafter. By the mid-1680s Harder and Zwinger had become established experimental researchers and Basel’s leading advocates of the “iatromechanical” and “iatrochemical” challenge to orthodox humoral medicine.4 Based on the faculty’s course catalog, Hofer’s biographer has estimated that the young student spent the bulk of his training learning about brain anatomy, the organs of the senses, organic viscera, and experimental chemistry with his professors.5 It is almost certainly in these classes that he was exposed to Descartes’s mechanistic philosophy and to important discoveries in brain anatomy, physiology, and neurology—all of which transpire in his written work. Hofer prepared his thesis on nostalgia under Harder’s guidance and defended it on June 22, 1688, in the manner of a “disputation” (disputatio), or a formalized debate with his professors (Harder, Zwinger, and the chairs of theoretical and practical medicine). This was only a preliminary requirement, submitted in preparation for the final examination and inaugural thesis, the disputatio medica inauguralis, which Hofer filed the following April on the somewhat less esoteric topic of uterine dropsy (De hydrope uteri).

As is often the case with early modern medical dissertations, it is difficult to establish beyond all doubt that the text actually is Hofer’s work. Twenty-first-century notions of authorship do not apply to a time when it was customary for professors and students to work collaboratively and share the honors. Typically, the former would write the text, whereas the latter would present and defend its claims in a public disputation. (This was especially useful for testing daring new ideas.)6 While it is, therefore, possible that Harder authored parts of the thesis, it does seem that Hofer was the primary authorial voice as he is clearly identified as “author” and not just as “respondent.” Moreover, he explicitly chose to present his research as a dissertatio—then a relatively new term conveying research based on hypotheses and empirical observations—rather than a more conventional disputatio (a codified recital of canonical knowledge).7

Whatever their exact contribution to the text itself, it is clear that Harder and Zwinger shaped Hofer’s medical training and helped him launch his career as a doctor through their connections. Harder made sure that his student’s thesis was published by a local printing press, Jacob Bertsch (an unusual accolade for a preliminary work).8 The text was subsequently reissued in revised form in a collection of notable dissertations that Zwinger edited in 1710. In fact, multiple editions would continue to be reprinted periodically, long after Hofer had moved back to Mulhouse and bracketed his medical vocation for a highly successful career in municipal politics. Intriguingly, several of these circulated under modified titles and were more or less explicitly attributed to Harder. As we will see in the next chapter, the vicissitudes of this “uncertain disease” (as nostalgia would come to be described) may be attributed at least in part to the editorial innuendo that clouded the disease’s paternity for much of the eighteenth century and beyond.

Heimweh to Nostalgia

Authorial conundrums aside, Hofer’s De Nostalgia is, in and of itself, a puzzling text that defies easy categorizations.9 At first sight, it appears to be a rather conventional example of the research produced by seventeenth-century European medical faculties. Its sixteen octavo pages of Latin prose are standard for the time, and its style is that of someone trained in the classical rhetorical and philosophical traditions. It bears formal similarities with countless other medical disputationes, including an elaborate dedication to the presiding professors and an annex (corollaria) of laudatory remarks and poems on the student by acquaintances. Its content is, likewise, straightforward enough: after providing a rationale for his choice of topic (Thesis I), Hofer defines his object of study by naming the condition (§II) and outlining its basic pathogenesis (§III). He subsequently presents two cases studies (§IV) and details the clinical picture with a discussion of predisposing factors (§V), the seat of the disease (§VI), its etiology—both internal (§VII) and external causes (§VIII)—and symptomatology (§IX). He concludes by revisiting the condition’s pathophysiology (§X), its prognosis (§XI), and therapeutic recommendations (§XII).

Still, identifying a new disease is no ordinary feat, and it would be unfair to dismiss Hofer’s dissertation as wholly unoriginal. In more ways than one, he epitomized what Roger French has called the “learned and rational doctor”—namely, the university-trained physician, mindful of tradition but increasingly versatile and at ease in the rapidly changing world of seventeenth-century medicine.10 Hofer certainly was no iconoclast, but he showed a keen interest in the pioneering experimental work of his time and was savvy enough to couch his findings in tentative terms. He explained his original topic choice as a matter of curiosity about mysterious stories of youngsters who succumbed to ill-defined “fevers” and “consumption” far from home. The Swiss, Hofer noted, already knew the disorder by the vernacular term “das Heim-weh,” literally “home-sickness.” The French also spoke of “la maladie du pays” to describe the “sorrow caused by the lost charm of the native land” among Swiss expatriates (§I). Neither of these terms, however, was scientific enough to properly define a disease (morbo). Hofer hesitated over the all-important task of naming this new clinical entity, at one point considering other neologisms such as “nosomania” (literally “return-madness”) and the more descriptive “philopatridomania” (“madness caused by yearning for the homeland”). His preference, though, lay with a third coinage, less precise but still sufficiently savant and decidedly more pleasing to the ear: “ΝΟΣΤΑΛΓΙΑ,” or “nostalgia,” from the Greek roots νόστος, or nostos (homecoming), and άλγος, or algos (pain or longing). Nostalgia, Hofer boldly asserted, would stand for the deep “sadness [tristem animum] arising from the burning desire to return to the homeland” (§II–III).

A counterfactual history could fruitfully speculate on what the term’s trajectory—and, perhaps, modernity’s course itself—might have been had Hofer, or his professors, finally opted for a more unwieldy term. Be that as it may, the choice of “nostalgia” was crucial not only because more euphonic, but because it distinguished the condition from conventional forms of madness. For Hofer, homesickness did not affect one’s reason or intellect as a whole, and it was not a particular kind of “mania” or a “frenzy.” Although it clearly entailed psychological suffering and sometimes even showed signs of “melancholic delirium” (delirii melancholici) (§III), as far as he could tell, it only targeted discrete mental faculties. But whereas a twenty-first-century reader might expect him to have singled out a faulty memory as the source of the ill, Hofer had another mental operation in mind—one that seemed most consonant with nostalgia’s ostensibly spatial, rather than temporal, coordinates. As he repeatedly made clear to his readers, nostalgia had to be understood first and foremost as the “symptom of a disordered imagination” (symptoma imaginationis laesae) (§III).

Hofer described the pathogenic process at the heart of the condition in the typical language of late seventeenth-century physiology. He posited that what troubled the imagination was the “constant movement of the animal spirits along the white tubules of the striate bodies and oval center of the brain” (§XI), where “residual impressions of the homeland [patriae] adhere” (§VII). Sensory stimulation induced this vibration, soliciting the imaginative faculties to converge on mental images [phantasmata] impressed in memory, and “excite in the soul [anima] a recurring and exclusive idea of returning to the homeland” (§III). Hofer viewed these vibrating spirits in corpuscular terms, as a quantifiable flow of fine particles that surged along nervous conduits setting in motion a chain reaction with both psychic and somatic consequences. The mind’s fixation on the idea of home blocked the actual flow of animal spirits, preventing them from sustaining the “vibration of the fibrils in the common sensorium [sensorio communi]” necessary to the proper functioning (multitasking) of the brain. Because of this hoarding, the spirits also could not flow in sufficient quantities “along the invisible channels that connect the various parts of the body,” thus affecting all other natural faculties. Hofer singled out loss of appetite and poor digestion due to diluted gastric juices, leading to an overly acidic chyle that would, in turn, yield viscous serum and thick lymph when mixed with blood. The end result was an overconsumption of animal spirits in the brain and lackluster regeneration of the same spirits in the blood, thus further slowing down all bodily and mental functions. In an advanced case, blood would begin to thicken and clot, hindering circulation and affecting the heart. At this stage the nostalgic patient might begin to develop aggravating somatic conditions, including bouts of anxiety, fever, and obstruction of the glands (§X). Hofer’s full symptomatology reads like a laundry list of morbid signs: “constant sadness [tristia continua], obsessive thinking about the homeland, insomnia and agitated sleep, general weakness, loss of appetite, heart palpitations, respiratory difficulties, [ . . . ] continuous and intermittent fevers” (§IX). His prognosis left little room for hope: if nostalgia was allowed to fester untreated, the “consumption of the spirits” and inexorable weakening of the body would hasten death by exhaustion (§XI).

Hofer embedded this detailed pathophysiological explanation within a more tentative examination of nostalgia’s broader epidemiology based on personal and related observations in his entourage. He started by distinguishing between preexisting chronic and acute conditions that might predispose to nostalgia on the one hand, and the difficulties encountered when trying to adapt to a change in lifestyle or habits following expatriation on the other. The latter clearly interested him most, and he singled out unfamiliar customs and foods, a marked change in atmosphere, and insults professed in a foreign language as possible triggers. A “homebound education” with little contact with the outside world, he claimed, was certain to produce socially inept adolescents incapable of “adapting to foreign ways of life” or, for that matter, of “forgetting their mother’s milk.” Hofer seems to have been uncomfortable with circulating rumors that Heimweh was a particularly Swiss malady—a topos emphasized at the end of his thesis, in a few short verses by the French Huguenot Charles Ancillon, who congratulated the author on having shown that a Swiss could cure what he described as a “national malady.” Despite only having Swiss examples at hand to rely upon, Hofer invoked the findings of other doctors across Europe to recuse the idea that this was a Schweizerkrankheit (and one that targeted the Bernese in particular). Why they seemed especially prone Hofer wasn’t quite sure, although he recognized that the predisposing factors seemed to apply particularly well to isolated alpine communities. Most interestingly, he s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Nostalgia as a Historical Problem

- 1 · Nostalgia in 1688

- 2 · The Reasons of a Passion

- 3 · The Lost Pays of the Patrie

- 4 · Mothers and Sons in the Time of Napoleonic War

- 5 · Golden Age

- 6 · Nostalgia in the Tropics

- 7 · Ubi bene, ibi patria: Nostalgia Fin de Siècle

- Afterword: Nostalgia in History

- List of Abbreviations

- Notes

- Archival Sources

- Index