- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

An engaging account of the largely forgotten world of early animated films from Hollywood and beyond

This witty and fascinating study reminds us that there was animation before Disney: about thirty years of creativity and experimentation flourishing in such extraordinary work as Gertiethe Dinosaur and Felix the Cat. Before Mickey, the first in-depth history of animation from the turn of the century until the debut of Disney, includes accounts of mechanical ingenuity, marketing, and art. Donald Crafton is equally adept at explaining techniques of sketching and camera work, evoking characteristic styles of such pioneering animators as Winsor McCay and Ladislas Starevitch, placing work in its social and economic context, and unraveling the aesthetic impact of specific cartoons.

This witty and fascinating study reminds us that there was animation before Disney: about thirty years of creativity and experimentation flourishing in such extraordinary work as Gertiethe Dinosaur and Felix the Cat. Before Mickey, the first in-depth history of animation from the turn of the century until the debut of Disney, includes accounts of mechanical ingenuity, marketing, and art. Donald Crafton is equally adept at explaining techniques of sketching and camera work, evoking characteristic styles of such pioneering animators as Winsor McCay and Ladislas Starevitch, placing work in its social and economic context, and unraveling the aesthetic impact of specific cartoons.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Before Mickey by Donald Crafton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Médias et arts de la scène & Film et vidéo. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Secret of the Haunted Hotel

Animation has bred a myth about its own origins that goes, according to the film historian’s lore, like this: Animation was virtually unknown until 1907. It was then that L’Hôtel hanté opened in Paris. The public response to this first animated film was so strong that all the French producers racked their brains trying to figure out the tricks that made objects move by themselves. After considerable difficulty, the secret was discovered and the history of cartoons could begin.

A close look at this legend shows that at least one part is true: The Haunted Hotel was a tremendous success. It was produced by the American Vitagraph company and released in the United States in March 1907. Business was so brisk that almost a year later it was still promoted as one of the company’s “recent hits.”1 It was directed by James Stuart Blackton, cofounder of Vitagraph, and photographed by his partner, Albert E. Smith. Like most films of the period, it began with a rather stagey long shot of a weary traveler seeking shelter at a mysterious hotel. Smith and Blackton were unconcerned with the originality of their plot; the idea had been filmed already by Georges Méliès, the French trick specialist, in L’ Hôtel empoisonné and Le Manoir du diable (1896), Le Château hanté and L’Auberge ensorcelée (1897), and L’Auberge du bon repos (1903). In England, G. A. Smith had shot The Haunted Castle (1897), and in America there had been Edison’s Uncle Josh in a Spooky Hotel (1900). Even long before the movies had been invented the “haunted hotel” had been a stage act at popular theaters like the Châtelet in Paris and at itinerant shows in Europe and America.

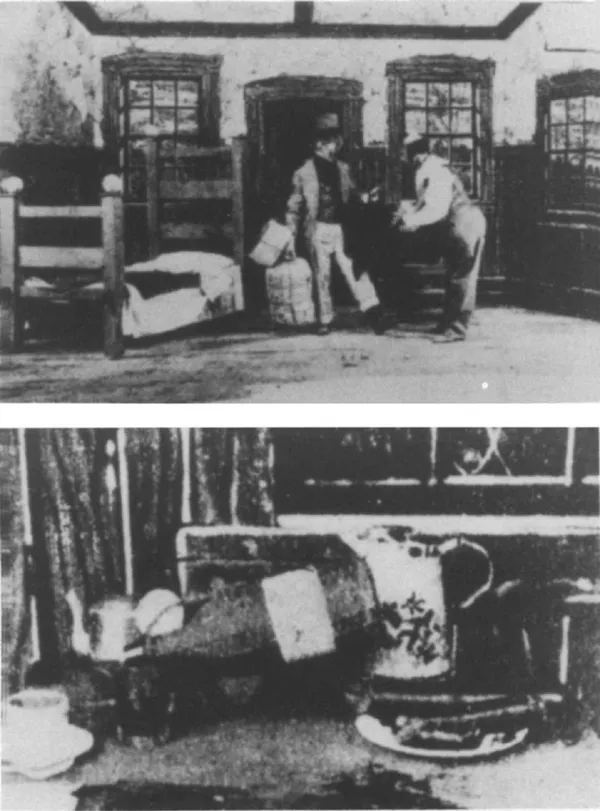

The gist of Blackton’s version of the story was simply that the usual manual labor around the inn was performed by invisible ghosts (figure 3). All the special effects of the time—lap dissolves, double exposures, and stop-action substitutions—were exploited to their limits. Wires were used to make objects move on their own, a technique of the nineteenth-century stage magician. One scene in particular astonished viewers. It showed a table being set, a wine bottle pouring its contents into a glass, and a knife slicing a loaf of bread, all in large closeup and without any apparent wires. The scene’s peculiar flickery, jerky quality enhanced its strangeness. It was animation.

Eager to be the first to gain a foothold on the European market, Vitagraph had opened an office in Paris at 15 rue Sainte-Cécile in February 1907. In April they were ready to take orders for their trickfilm L’Hôtel hanté; fantasmagorie épouvantable.2 It was the custom then to sell copies of films outright to exhibitors, who resold them to second-run theaters and traveling shows at lower prices. Vitagraph’s film quickly became the best-selling American movie in France, and in all of Europe over 150 new prints would be delivered.3 The film was a sensation at the Châtelet, where it ran twice daily from July 17 through July 29, and at the Hippodrome, which with 5,000 seats was the world’s largest cinema. France’s second largest producer, Gaumont, bought prints and distributed them as its own.4

Why was The Haunted Hotel a success? An early French director, Victorin Jasset, was the first to suggest that it was because the camera was close enough to the table top to eliminate the possibility of the usual theatrical tricks: “The Vitagraph film The Haunted Hotel was a sensation and rightly so. Abandoning all the tricks of the movies, they had contrived entirely new and totally unexpected combinations of techniques. As we watched, the sharpest, most attentive eye was unable to detect any wires. One had to be informed of the process.”5 Furthermore, the length of the animated sequences gave the audience sufficient time to ponder the trick. Then, too, the film arrived at a time when American things were in vogue, and according to Jasset it was considered the most typically American film yet seen in Europe. Indeed, until World War I the French technical term for animation remained “le mouvement américain.”

Figure 3.

James Stuart Blackton, The Haunted Hotel (Vitagraph), © 1907.

James Stuart Blackton, The Haunted Hotel (Vitagraph), © 1907.

But there was also a more pragmatic reason for The Haunted Hotel’s success. Vitagraph launched the film with a flourish of hyperbolic advertising:

Impressive, indefinable, insoluble, positively the most marvelous film ever invented. Here are some of the mysterious moments in the film: a house which changes into an organ, a table set by invisible hands, a knife which really cuts slices of sausage and bread. Wine, tea and milk pouring themselves. All without the aid of any hand. There is a quantity of other equally strange effects, among them, a bedroom which spins around completely while the poor frightened traveler trembles in his bed wondering what will happen next. A real novelty.6

Such ballyhoo was already common in American advertising, but French films were still announced only by title, genre, and length. This unaccustomed aggressiveness would quickly establish Vitagraph’s European base, and The Haunted Hotel was the company’s first marketing test. There is no question that animation captured the public’s imagination in the wake of this American hit. Contemporary press accounts confirm that Parisians were lining up to see the film just to guess at how the tricks were done. One of the engrossed spectators was a staff writer for the important weekly L’Illustration, Gustave Babin, an admirer of the cinema ever since his friend the poet Armand Silvestre (a personal friend of the Lumière brothers) had introduced him to the movies’ hypnotic attraction. In the spring of 1908, Babin went to the Gaumont studios in Belleville to prepare two articles that have since become key documents in the early history of film.7

The task of explaining the various trick effects fell upon Anatole Thiberville, a Gaumont veteran since the turn of the century. Formerly a farmer from Bresse, he had begun working for the company when it still sold amateur photographic gear. Despite his detailed descriptions, however, Babin was not satisfied and insisted upon learning the secret of The Haunted Hotel:

All amateurs and habitués of the cinema who know its repertoire have seen those mysterious scenes I mean: a table loaded with food which is consumed, no one knows how, by some invisible being, something like the Spirit of the Ancestors for which Victor Hugo, in his Guernesey gatherings, reserved an empty seat. A bottle pours its own wine into a glass, a knife hurls itself onto a loaf of bread, then slices into a sausage; a wicker basket weaving itself; tools performing their work without the cooperation of any artisan. So many strange marvels that one could see every night for several months. And even tipped off as I was, and as my readers are, I still could not find the last word of the riddle.

Much to Babin’s perplexity, Thiberville refused to reveal this trade secret: “‘I searched for months, Mr. Babin, and about eight or so ago I found the solution. These films which intrigue you so much are American. They pestered us no less than you. I have just successfully completed the first of this kind [in France]. But as to revealing the mystery to you’—and his smile became more amiable and at the same time more malicious—‘that is absolutely impossible at the present. And you must believe how much I regret it.’”

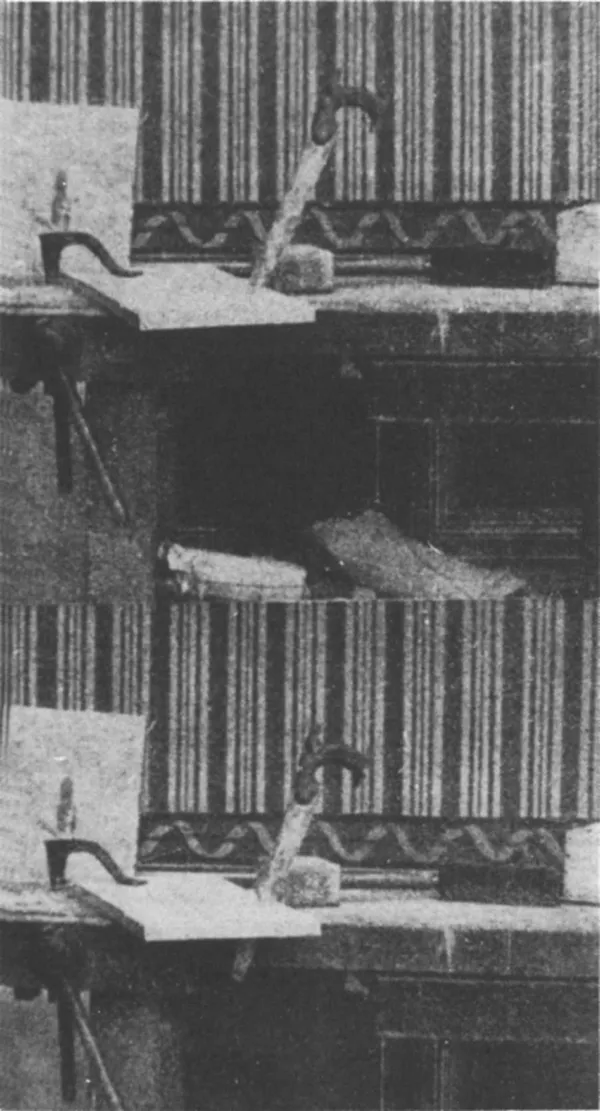

Babin’s curiosity was only further inflamed when Thiberville projected this latest film, Le Travail rendu facile (Work Made Easy) (figure 4): “Marvel of marvels! A carpenter’s shop, a bench with a vise, a hammer and a saw, all at work without my being able to perceive any human hand. There’s the real miracle. And the question we have asked so many times returns: ‘How do they do it?’ Me, I’ve thrown in the towel. But perhaps among the readers of L’Illustration someone devoted to riddles will be ingenious enough to give us the solution. Maybe it’s very simple.”

Thiberville’s story of the discovery of the secret of animation was later retold more dramatically by another eyewitness—his Gaumont colleague, cameraman Etienne Arnaud:

There were three of us metteurs en scène who had received from the big boss, Léon Gaumont, the mission of going to find out by what really diabolical means objects could appear to be moving on the screen without any human intervention. We went through three consecutive screenings. Louis Feuillade left more myopic because he had popped his eyes searching for the wires that he thought made the objects move. Jacques Roullet concluded it was an “affaire mystérieuse” and decided to submit it to the Pinkertons. As for me, I was particularly vexed because I was supposed to be the specialist in trick scenes and frankly this new film from overseas dropped in completely out of the blue.8

Finally, according to Arnaud, it was a newcomer at the studio, Emile Cohl, who unlocked the secret. The camera was fixed so that each turn of the crank permitted the exposure of only one image. After each turn, the director would move the objects on the table a few millimeters, step out of the way for another take, then repeat the process. Thus was the fundamental technical procedure, frame-by-frame exposure, introduced into France.

Figure 4.

Work Made Easy (Vitagraph, 1907). From Babin, “Les Coulisses du cinématographe.”

Work Made Easy (Vitagraph, 1907). From Babin, “Les Coulisses du cinématographe.”

By these firsthand accounts, it was the absolute novelty of The Haunted Hotel and the frantic rush by European producers to decipher the technique that fomented an animation explosion in 1908. But the available facts raise questions.

The alleged ignorance of these experienced cameramen is very baffling, because The Haunted Hotel was by no means the first animated film. The technique was almost as old as cinematography. Mechanically, even the earliest cameras were capable of single-frame takes. Their shutters usually consisted of a disk with a single hole rotating in such a way as to expose one frame per quarter, half, or whole revolution, depending on the particular gear system in use. It was theoretically a simple matter for an intelligent cameraman to determine the positions during cranking when the shutter was closed, to pause and move the object being photographed, and to continue. Later cameras were geared to make one exposure per turn and automatically stop with the shutter closed, but these were alterations of convenience, not of necessity. Of course it took a skillful operator to manually achieve consistent exposures for each frame, and failure to do so produced the flickering that marked most early animated scenes.

The earliest date suggested for the discovery of this technique is 1898. It was around then that Blackton and Smith, the producers of The Haunted Hotel, noticed some curious defects in one of their films. Many years after it happened, Smith recalled that they had been shooting a Méliès-style trickfilm on the roof of the Morse Building, their new “studio” in New York. During the intervals between takes, while the trick substitutions were being made, clouds of steam from the building’s electrical generator would drift across the background. When the film was projected these puffs appeared, disappeared, and jumped about the screen most unexpectedly:

These unplanned adventures with puffs of steam led us to some weird effects. In A Visit to the Spiritualist wall pictures, chairs and tables flew in and out, and characters disappeared willy-nilly—done by stopping the camera, making the changes, and starting again. . . . Vitagraph made the first stop-motion picture in America, The Humpty Dumpty Circus. I used my little daughter’s set of wooden circus performers and animals, whose movable joints enabled us to place them in balanced positions. It was a tedious process inasmuch as the movement could be achieved only by photographing separately each change of position. I suggested we obtain a patent on the process; Blackton felt it wasn’t important enough. However, others quickly borrowed the technique, improving upon it gready.9

Among the borrowers were technicians at the Edison studio who knew the two young entrepreneurs. Recently rediscovered Edison films from the 1905 period, such as How Jones Lost His Roll, reveal animated title cards.10 Blackton seems not to have reused the idea until early 1906, when he made Humorous Phases of Funny Faces. It occurred to him that...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Frontispiece

- Dedication

- Note to the 1993 Edition

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Foreword

- Preface

- Animation: Myth, Magic, and Industry

- 1. The Secret of the Haunted Hotel

- 2. From Comic Strip and Blackboard to Screen

- 3. The First Animator: Emile Cohl

- 4. “Watch Me Move!” The Films of Winsor McCay

- 5. The Henry Ford of Animation: John Randolph Bray

- 6. The Animation “Shops”

- 7. Commercial Animation in Europe

- 8. Automated Art

- 9. Felix; or, Feline Felicity

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Afterword, Errata, and Update

- Selected Bibliography

- Index