- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"[Mitchell] undertakes to explore the nature of images by comparing them with words, or, more precisely, by looking at them from the viewpoint of verbal language. . . . The most lucid exposition of the subject I have ever read."—Rudolf Arnheim, Times Literary Supplement

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Iconology by W. J. T. Mitchell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

The Idea of Imagery

It is one thing . . . to apprehend directly an image as image, and another thing to shape ideas regarding the nature of images in general.

Jean-Paul Sartre, Imagination (1962)

Any attempt to grasp “the idea of imagery” is fated to wrestle with the problem of recursive thinking, for the very idea of an “idea” is bound up with the notion of imagery. “Idea” comes from the Greek verb “to see,” and is frequently linked with the notion of the “eidolon,” the “visible image” that is fundamental to ancient optics and theories of perception. A sensible way to avoid the temptation of thinking about images in terms of images would be to replace the word “idea” in discussions of imagery with some other term like “concept” or “notion,” or to stipulate at the outset that the term “idea” is to be understood as something quite different from imagery or pictures. This is the strategy of the Platonic tradition, which distinguishes the eidos from the eidolon by conceiving of the former as a “suprasensible reality” of “forms, types, or species,” the latter as a sensible impression that provides a mere “likeness” (eikon) or “semblance” (phantasma) of the eidos.1

A less prudent, but I hope more imaginative and productive, way of dealing with this problem is to give in to the temptation to see ideas as images, and to allow the recursive problem full play. This involves attention to the way in which images (and ideas) double themselves: the way we depict the act of picturing, imagine the activity of imagination, figure the practice of figuration. These doubled pictures, images, and figures (what I will refer to—as rarely as possible—as “hypericons”) are strategies for both giving into and resisting the temptation to see ideas as images. Plato’s cave, Aristotle’s wax tablet, Locke’s dark room, Wittgenstein’s hieroglyphic are all examples of the “hypericon” that, along with the popular trope of the “mirror of nature,” provide our models for thinking about all sorts of images—mental, verbal, pictorial, and perceptual. They also provide, I will argue, the scenes in which our anxieties about images can express themselves in a variety of iconoclastic discourses, and in which we can rationalize the claim that, whatever images are, ideas are something else.

1

What Is an Image?

There have been times when the question “What is an image?” was a matter of some urgency. In eighth- and ninth-century Byzantium, for instance, your answer would have immediately identified you as a partisan in the struggle between emperor and patriarch, as a radical iconoclast seeking to purify the church of idolatry, or a conservative iconophile seeking to preserve traditional liturgical practices. The conflict over the nature and use of icons, on the surface a dispute about fine points in religious ritual and the meaning of symbols, was actually, as Jaroslav Pelikan points out, “a social movement in disguise” that “used doctrinal vocabulary to rationalize an essentially political conflict.”1 In mid-seventeenth-century England the connection between social movements, political causes, and the nature of imagery was, by contrast, quite undisguised. It is perhaps only a slight exaggeration to say that the English Civil War was fought over the issue of images, and not just the question of statues and other material symbols in religious ritual but less tangible matters such as the “idol” of monarchy and, beyond that, the “idols of the mind” that Reformation thinkers sought to purge in themselves and others.2

If the stakes seem a bit lower in asking what images are today, it is not because they have lost their power over us, and certainly not because their nature is now clearly understood. It is a commonplace of modern cultural criticism that images have a power in our world undreamed of by the ancient idolaters.3 And it seems equally evident that the question of the nature of imagery has been second only to the problem of language in the evolution of modern criticism. If linguistics has its Saussure and Chomsky, iconology has its Panofsky and Gombrich. But the presence of these great synthesizers should not be taken as a sign that the riddles of language or imagery are finally about to be solved. The situation is precisely the reverse: language and imagery are no longer what they promised to be for critics and philosophers of the Enlightenment—perfect, transparent media through which reality may be represented to the understanding. For modern criticism, language and imagery have become enigmas, problems to be explained, prison-houses which lock the understanding away from the world. The commonplace of modern studies of images, in fact, is that they must be understood as a kind of language; instead of providing a transparent window on the world, images are now regarded as the sort of sign that presents a deceptive appearance of naturalness and transparence concealing an opaque, distorting, arbitrary mechanism of representation, a process of ideological mystification.4

My purpose in this chapter is neither to advance the theoretical understanding of the image nor to add yet another critique of modern idolatry to the growing collection of iconoclastic polemics. My aim is rather to survey some of what Wittgenstein would call the “language games” that we play with the notion of images, and to suggest some questions about the historical forms of life that sustain those games. I don’t propose, therefore, to produce a new or better definition of the essential nature of images, or even to examine any specific pictures or works of art. My procedure instead will be to examine some of the ways we use the word “image” in a number of institutionalized discourses—particularly literary criticism, art history, theology, and philosophy—and to criticize the ways each of these disciplines makes use of notions of imagery borrowed from its neighbors. My aim is to open up for inquiry the ways our “theoretical” understanding of imagery grounds itself in social and cultural practices, and in a history fundamental to our understanding not only of what images are but of what human nature is or might become. Images are not just a particular kind of sign, but something like an actor on the historical stage, a presence or character endowed with legendary status, a history that parallels and participates in the stories we tell ourselves about our own evolution from creatures “made in the image” of a creator, to creatures who make themselves and their world in their own image.

The Family of Images

Two things must immediately strike the notice of anyone who tries to take a general view of the phenomena called by the name of imagery. The first is simply the wide variety of things that go by this name. We speak of pictures, statues, optical illusions, maps, diagrams, dreams, hallucinations, spectacles, projections, poems, patterns, memories, and even ideas as images, and the sheer diversity of this list would seem to make any systematic, unified understanding impossible. The second thing that may strike us is that the calling of all these things by the name of “image” does not necessarily mean that they all have something in common. It might be better to begin by thinking of images as a far-flung family which has migrated in time and space and undergone profound mutations in the process.

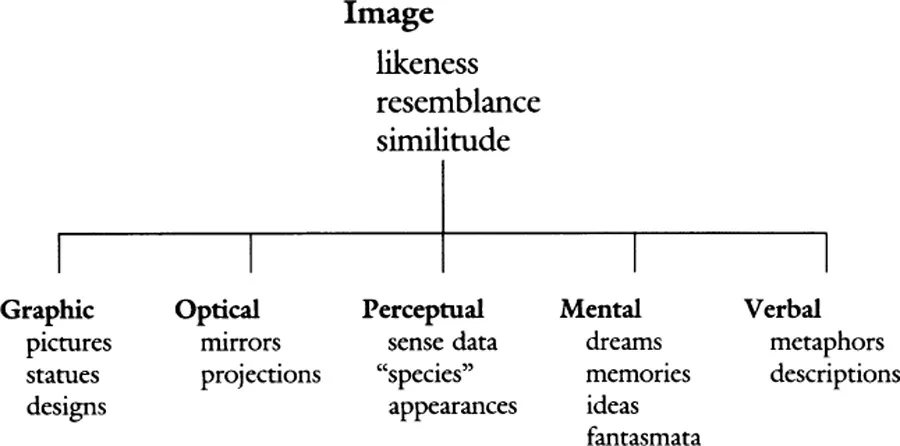

If images are a family, however, it may be possible to construct some sense of their genealogy. If we begin by looking, not for some universal definition of the term, but at those places where images have differentiated themselves from one another on the basis of boundaries between different institutional discourses, we come up with a family tree something like the following:

Each branch of this family tree designates a type of imagery that is central to the discourse of some intellectual discipline: mental imagery belongs to psychology and epistemology; optical imagery to physics; graphic, sculptural, and architectural imagery to the art historian; verbal imagery to the literary critic; perceptual images occupy a kind of border region where physiologists, neurologists, psychologists, art historians, and students of optics find themselves collaborating with philosophers and literary critics. This is the region occupied by a number of strange creatures that haunt the border between physical and psychological accounts of imagery: the “species” or “sensible forms” which (according to Aristotle) emanate from objects and imprint themselves on the wax like receptacles of our senses like a signet ring;5 the fantasmata, which are revived versions of those impressions called up by the imagination in the absence of the objects that originally stimulated them; “sense data” or “percepts” which play a roughly analogous role in modern psychology; and finally, those “appearances” which (in common parlance) intrude between ouselves and reality, and which we so often refer to as “images”—from the image projected by a skilled actor, to those created for products and personages by experts in advertising and propaganda.

The history of optical theory abounds with these intermediate agencies that stand between us and the objects we perceive. Sometimes, as in the Platonic doctrine of “visual fire” and the atomistic theory eidola or simulacra, they are understood as material emanations from objects, subtle but nevertheless substantial images propagated by objects and forcibly impressing themselves on our senses. Sometimes the species are regarded as merely formal entities, without substance, propagated through an immaterial medium. And some theories even describe the transmission as moving in the other direction, from our eyes to the objects. Roger Bacon provides a good synthesis of the common assumptions of ancient optical theory:

Every efficient cause acts through its own power, which it exercises on the adjacent matter, as the light [lux] of the sun exercises its power on the air (which power is light [lumen] diffused through the whole world from the solar light [lux]). And this power is called “likeness,” “image,” and “species” and is designated by many other names. . . . This species produces every action in the world, for it acts on sense, on the intellect, and on all matter of the world for the generation of things.6

It should be clear from Bacon’s account that the image is not simply a particular kind of sign but a fundamental principle of what Michel Foucault would call “the order of things.” The image is the general notion, ramified in various specific similitudes (convenientia, aemulatio, analogy, sympathy) that holds the world together with “figures of knowledge.”7 Presiding over all the special cases of imagery, therefore, I locate a parent concept, the notion of the image “as such,” the phenomenon whose appropriate institutional discourses are philosophy and theology.

Now each of these disciplines has produced a vast literature on the function of images in its own domain, a situation that tends to intimidate anyone who tries to take an overview of the problem. There are encouraging precedents in work that brings together different disciplines concerned with imagery, such as Gombrich’s studies of pictorial imagery in terms of perception and optics, or Jean Hagstrum’s inquiries into the sister arts of poetry and painting. In general, however, accounts of any one kind of image tend to relegate the others to the status of an unexamined “background” to the main subject. If there is a unified study of imagery, a coherent iconology, it threatens to behave, as Panofsky warned, “not like ethnology as opposed to ethnography, but like astrology as opposed to astrography.”8 Discussions of poetic imagery generally rely on a theory of the mental image improvised out of the shreds of seventeenth-century notions of the mind;9 discussions of mental imagery depend in turn upon rather limited acquaintance with graphic imagery, often proceeding on the questionable assumption that there are certain kinds of images (photographs, mirror images) that provide a direct, unmediated copy of what they represent;10 optical analyses of mirror images resolutely ignore the question of what sort of creature is capable of using a mirror; and discussions of graphic images tend to be insulated by the parochialism of art history from excessive contact with the broader issues of theory or intellectual history. It would seem useful, therefore, to attempt an overview of the image that scrutinizes the boundary lines we draw between different kinds of images, and criticizes the assumptions which each of these disciplines makes about the nature of images in neighboring fields.

We clearly cannot talk about all these topics at once, so the next question is where to start. The general rule is to begin with the basic, obvious facts and to work from there into the dubious or problematic. We might start, then, by asking which members of the family of images are called by that name in a strict, proper, or literal sense, and which kinds involve some extended, figurative, or improper use of the term. It is hard to resist the conclusion that the image “proper” is the sort of thing we found on the left side of our tree-diagram, the graphic or optical representations we see displayed in an objective, publicly shareable space. We might want to argue about the status of certain special cases and ask whether abstract, nonrepresentational paintings, ornamental or structural designs, diagrams and graphs are properly understood as images. But whatever borderline cases we might wish to consider, it seems fair to say that we have a rough idea about what images are in the literal sense of the word. And along with this rough idea goes a sense that other uses of the word are figurative and improper.

The mental and verbal images on the right side of our diagram, for instance, would seem to be images only in some doubtful, metaphoric sense. People may report experiencing images in their heads while reading or dreaming, but we have only their word for this; there is no way (so the argument goes) to check up on this objectively. And even if we trust the reports of mental imagery, it seems clear that they must be different from real, material pictures. Mental images don’t seem to be stable and permanent the way real images are, and they vary from one person to the next: if I say “green,” some listeners may see green in their mind’s eye, but some may see a word, or nothing at all. And mental images don’t seem to be exclusively visual the way real pictures are; they involve all the senses. Verbal imagery, moreover, can involve all the senses, or it may involve no sensory component at all, sometimes suggesting nothing more than a recurrent abstract idea like justice or grace or evil. It is no wonder that literary scholars get very nervous when people start taking the notion of verbal imagery too literally.11 And it is hardly surprising that one of the main thrusts of modern psychology and philosophy has been to discredit the notions of both mental and verbal imagery.12

Eventually I will argue that all three of these commonplace contrasts between images “proper” and their illegitimate offspring are suspect. That is, I hope to show that, contrary to common belief, images “proper” are not stable, static, or permanent in any metaphysical sense; they are not perceived in the same way by viewers any more than are dream images; and they are not exclusively visual in any important way, but involve multisensory apprehension and interpretation. Real, proper images have more in common with their bastard children than they might like to admit. But for the moment let us take these proprieties at face value, and examine the genealogy of those illegitimate notions, images in the mind and images in language.

The Mental Image: A Wittgensteinian Critique

Now for the thinking soul images take the place of direct perceptions; and when it asserts or denies that they are good or bad, it avoids or pursues them. Hence the soul never thinks without a mental image.

Aristotle, De Anima 111.7.431a

A notion with the entrenched authority of three hundred years of institutionalized research and speculation behind it is not going to give up without a struggle. Mental imagery has been a central feature of theories of the mind at least since Aristotle’s De Anima, and it continues to be a cornerstone of psychoanalysis, experimental studies of perception, and popular folk-beliefs about the mind.13 The...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Iconology

- Part One: The Idea of Imagery

- Part Two: Image versus Text: Figures of the Difference

- Part Three: Image and Ideology

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index