- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

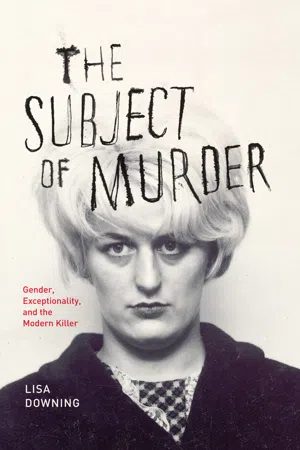

The subject of murder has always held a particular fascination for us. But, since at least the nineteenth century, we have seen the murderer as different from the ordinary citizen—a special individual, like an artist or a genius, who exists apart from the moral majority, a sovereign self who obeys only the destructive urge, sometimes even commanding cult followings. In contemporary culture, we continue to believe that there is something different and exceptional about killers, but is the murderer such a distinctive type? Are they degenerate beasts or supermen as they have been depicted on the page and the screen? Or are murderers something else entirely?

In The Subject of Murder, Lisa Downing explores the ways in which the figure of the murderer has been made to signify a specific kind of social subject in Western modernity. Drawing on the work of Foucault in her studies of the lives and crimes of killers in Europe and the United States, Downing interrogates the meanings of media and texts produced about and by murderers. Upending the usual treatment of murderers as isolated figures or exceptional individuals, Downing argues that they are ordinary people, reflections of our society at the intersections of gender, agency, desire, and violence.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Subject of Murder by Lisa Downing in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9780226003689Subtopic

World HistoryPART I

Murder and Gender in the European Nineteenth Century

CHAPTER ONE

“Real Murderer and False Poet”

Pierre-François Lacenaire

Here’s a gripping and terrible sensation; here’s Lacenaire!

He carried a lyre and a dagger!

He was a poet and he killed!

—(Hippolyte Bonnelier, Autopsie physiologique de Lacenaire, 1836)1

At once soft and ferocious

Its form holds for the viewer

I know not what atrocious grace

The grace of the gladiator!

Criminal aristocracy,

Neither plane nor hammer

Has hardened its skin

For his instrument was a knife.

For sacred calluses of honest labor

One searches in vain the trace.

Real murderer and false poet

He was the Manfred of the gutter.

—(Théophile Gautier, “Etude de mains: Lacenaire,” 1852)2

The lines of verse that form the epigraph of this chapter tellingly reveal a characteristic of the discourses that surrounded the case of Pierre-François Lacenaire (1803–1836), a murderer, forger, and thief, a dandy, and a poet, and the figure at the center of an aesthetic, media, and medical circus in the first years of the July Monarchy in France. Into his medical report on the phrenology and physiology of the killer,3 Hyppolite Bonnelier inserts lines of doggerel attesting sensationally to the qualities of Lacenaire—poet and murderer both. In his poem, which meditates on the severed hand of the infamous poet-murderer, Théophile Gautier meticulously dissects the appearance of the hand to read traces of the murderer’s personality in a passable imitation of the methods of the science of the time.4 Both writers, then, physician and poet alike, bend and blend their discursive resources in order to draw attention to the extraordinariness of Lacenaire and to celebrate the proximity of his artistry and criminality. These examples of testimonies to Lacenaire’s singularity are only two of many, produced in the discourses of science, politics, the press, medicine, and art. The considerable proliferation of texts inspired by the case, and more specifically by the figure of Lacenaire, who was tried in 1835 and executed in 1836, bears witness to a very specific and long-lasting cultural fantasy of the links between destruction and creation, individuality and society, for which Lacenaire provided the locus in the French nineteenth century.

Lacenaire’s actual crimes were neither particularly numerous nor particularly impressive. He was convicted of a double murder and a bungled attempted third killing. The murder victims were the Widow Char-don, whose body was found in a severely mutilated condition, and her son. The surviving victim was a bank employee, Genevay, whom Lacenaire attempted to kill with his sidekicks, the petty criminals known as “François et Avril” (Victor Avril and François Martin). Lacenaire had previously served prison terms for forgery and theft, and reputedly considered prison to be a “school of crime.” As Edward Baron Turk has put it, Lacenaire “distinguished himself less for his crimes than for his aesthetic attitude toward them.”5

If the case of Lacenaire excited a disproportionate wealth of reactions and opinions from a variety of ideological and political factions, this is perhaps due to his status as an educated, creative, and bourgeois killer—a “new” type of criminal subject. Foucault calls Lacenaire the “symbolic figure of an illegality kept within the bounds of delinquency and transformed into discourse—that is to say, made doubly inoffensive; the bourgeoisie had invented for itself a new pleasure, which it has still far from outgrown.”6 The idea that criminality might issue from, and appeal to, the bourgeoisie was seen as a different kind of danger than the one delinquency had previously been seen to pose. As Chevalier’s influential book on crime in nineteenth-century France demonstrates,7 criminality became a paranoid obsession of the nineteenth-century imaginary owing to the assumption that delinquency was a product of working-class insubordination, and that, like the “masses,” its threat was plural and anonymous. Balzac summed up this idea that criminals constituted a subterranean group, operating secretly to destabilize society, when he described, in 1825, “a nation apart, in the middle of the nation.”8 In contrast to this perception, Lacenaire embodied dissidence from within the ranks of the artistic elite. The cult of personality that blossomed around Lacenaire announced the underside of the rise of the individual associated with post-Revolutionary society. For, in Lacenaire, crime had both a single name and a single face, and it articulated its reason in articles sent from prison to the newspapers and promptly published, and in rhyme.

Gautier famously termed Lacenaire “vrai meurtrier et faux poète” (real murderer and false poet), a formula about which I will have more to say later with regard to the discourses of subjective authenticity to which it appeals, while Lacenaire, in his own memoirs, had identified himself more simply (and flatteringly) as a “poète-né” (“born poet”), endowed with “a veritable natural gift.”9 The myth of Lacenaire as both murderer and poet is indeed extraordinary in its ability to extend beyond his own personal history and immediate cultural context. Not only did the case and trial of Lacenaire set the tongues of 1830s Paris wagging, but the figure of Lacenaire would go on to be associated with the creation of a particular kind of murderer in the European cultural imaginary—the artistic creator of the murderous act, who produced poems in addition to corpses, and both with the same attention to artistry and flair. While the figure of the criminal artist has a genealogy that extends back beyond the nineteenth century—Sade being its most obvious exemplar—I will be arguing that the specificity of this discourse in Romantic and post-Romantic French culture lies in giving rise to a recognizable (fantasy) identity for the murderer, an ontology that would cross seas and continents and endure for centuries, in order to give Western society an archetype of gentlemanly murderous subjectivity.

Lacenaire has been immortalized in works of literature and on celluloid by names as diverse as Victor Hugo, Théophile Gautier, Rachilde, Honoré de Balzac, Stendhal,10 Fyodor Dostoyevsky,11 Marcel Carné, and Francis Girod. Charles Baudelaire named him “one of the heroes of modern life” (“un des héros de la vie moderne”).12 It will be the task of this chapter to explore the precise filiations between commentaries on the murderer (both autobiographical texts and those authored by others) and the traces he left on the cultural imagination. By so doing, I hope to articulate the ways in which the figure of the aesthete murderer became a prized locus of debates about subjectivity, class, gender, sexuality, and creativity in the 1830s in France and beyond.

Lacenaire in Context: The Most Frenetic of All the Romantics

The “popularity” of Lacenaire in the 1830s was not a phenomenon that emerged ex nihilo, but rather the symptom of a cultural trend. The facts of Lacenaire’s case, as they were conveyed by a fascinated media, appeared to dramatize several of the philosophical, aesthetic, and political obsessions of the zeitgeist. For the group of young Romantic and republican writers of the 1830s, known as the Bouzingos or Jeunes France, among them Pétrus Borel, Alexandre Dumas, Gérard de Nerval, and Théophile Gautier, Lacenaire fulfilled the role of a talismanic hero, a symbol of the transgression of artistic and lawful limits.13 This group, which pledged to fight against the philistinism associated with the new order of Louis Philippe, was personally familiar with Lacenaire, who, like them, frequented the workshop of the sculptor Duseigneur in the early 1830s. During Lacenaire’s incarceration, members of the group, including Dumas and Gautier, would visit him in prison, while their mentor, Victor Hugo, dedicated his first person narrative “Le Dernier jour d’un condamné” (“The Final Day of a Condemned Man”) to Pierre-François. Following Lacenaire’s execution, in a very literal and material, if somewhat gruesome, gesture, Maxime du Camp allegedly acquired the severed hand of the murderer, freshly cut from the gallows, inspiring Gautier to pen “Étude de mains: Lacenaire.”

The type of attention brought to bear on the case and figure of Lacenaire by his artistic contemporaries can be summarized under two headings: political and aesthetic. In stark definition to the ordered, progressive new bourgeois class, the young Romantics (many of whom were, of course, middle class or aristocratic by birth) cultivated an affectation of bohemian eccentricity. The dandified figure of Lacenaire, producer of a handful of political poems and famed for his insouciance in the face of his own condemnation, was co-opted for their republican political project and made to signify against the society they hated. In “Quel malheur ou Les regrets d’un doctrinaire” (“What misfortune or the regrets of a doctrinarian”), Lacenaire concludes with the following two stanzas:

In this baneful age,

Repudiating even his name,

In this hated Paris

If he were to reign, despite being a Bourbon,

I am certain that our king

Would think today, like me,

What misfortune!

I say it with distaste

Our three glorious days were a waste!

To reassure the homeland

About a similar attack

Against the furious press

We need a coup d’état.

Fines and prohibitions

Have not put us back in surplus

What misfortune!

I say it with distaste

Our three glorious days were a waste!14

The poem’s stridently anti–July Monarchy sentiment, marked by its ironic appeal to the even more repressive fallen Bourbon monarch, belies the fact that elsewhere in his writings, Lacenaire declared that he was by no means a committed political activist and confessed himself indifferent to the details of political reality.15 The availability of this stereotype of the committed rebel, corroborated by well-chosen sections of verse like the one cited above, was useful, however, for the aesthetic and political groups that adopted him as their byword for dissent.

For the press of the government, the politicization of Lacenaire was a dangerous gesture, according a revolutionary power to criminal force and providing a rhetorical weapon for oppositional factions. This explains, perhaps, the attempts to downplay the importance of Lacenaire as a man of his time in the conservative press. One commentator wrote in the Journal de Paris in November 1835:

The press has jumped on the trial of Lacenaire to incriminate either contemporary society or power. Some attack the corruption of the century, others what they call the immorality of the rulers. It would be more reasonable to regard Lacenaire as a terrible exception, of the kind that have appeared under all regimes and in all periods, but, happily for humanity, at rare intervals.16

Seeing the murderer as a “terrible exception” and as an ahistorical phenomenon—an aberration of the universal human genus that could occur in any epoch—rather than as the embodiment of the troubled and divided zeitgeist was an attempt to diffuse the power that Lacenaire wielded for his public and to make vanish the specters of the Revolution that discourses surrounding him threatened to evoke. It was, perhaps, precisely for this reason that the dissident writers of the day chose to play up his doubtful political affiliation, making him appear as an avenging angel of the republican and revolutionary spirit rather than as (just) an apolitical artist.

It has been argued that Romanticism presaged a democratization of literature. This obtained to some extent at the levels of both subject matter and profession, and the two were inextricably linked. Romanticism’s turn away from the epic and collective concerns of neoclassicism toward individual and personal introspection was accompanied by the fact that the profession of writer was increasingly potentially open to the bourgeois as well as to the aristocrat. This elicited pessimistic commentaries from antiliberal commentators. In a world in which anyone, regardless of class affiliation, could become a writer, according to Philarète Chasles, critic for La Chronique de Paris: “the story of our literature and of our authors will soon be told in the Gazette des tribuneaux [a popular, often sensationalist, publication giving details of crimes and trials].”17 Lacenaire, understandably, was seen as the actualized embodiment of this premonition.

The figure of Lacenaire arrived on the Romantic scene as an amalgam of existing archetypes as well as an innovator of a new criminal subject. The figure of the creative outlaw had already made his appearance in English Romantic literature during the 1820s with Byron’s poetic heroes, and some newspaper articles went so far as to suggest that Lacenaire was attempting deliberate imitation of these sublime role models, citing “les ravages du romantisme” (“the ravages of Romanticism”) which encouraged criminals to believe “that by dint of villainy and cynical perversity, they can redeem themselves from the horror they inspire and acquire admirers.”18 The problem, of course, was that this was exactly the response Lacenaire received from his fellow Romantics and a generation of ardent readers.

As well as the Byronic hero, acknowledg...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I . Murder and Gender in the European Nineteenth Century

- Part II. The Twentieth-Century Anglo-American Killer

- By Way of Brief Conclusion . . .

- Notes

- Index