- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

During the Progressive Era, a rehabilitative agenda took hold of American juvenile justice, materializing as a citizen-and-state-building project and mirroring the unequal racial politics of American democracy itself. Alongside this liberal "manufactory of citizens," a parallel structure was enacted: a Jim Crow juvenile justice system that endured across the nation for most of the twentieth century.

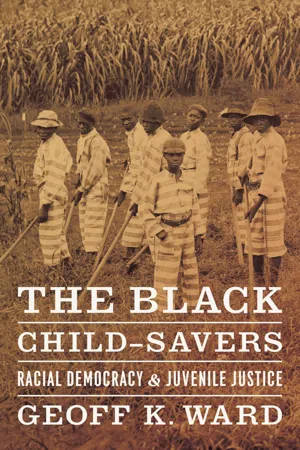

In The Black Child Savers, the first study of the rise and fall of Jim Crow juvenile justice, Geoff Ward examines the origins and organization of this separate and unequal juvenile justice system. Ward explores how generations of "black child-savers" mobilized to challenge the threat to black youth and community interests and how this struggle grew aligned with a wider civil rights movement, eventually forcing the formal integration of American juvenile justice. Ward's book reveals nearly a century of struggle to build a more democratic model of juvenile justice—an effort that succeeded in part, but ultimately failed to deliver black youth and community to liberal rehabilitative ideals.

At once an inspiring story about the shifting boundaries of race, citizenship, and democracy in America and a crucial look at the nature of racial inequality, The Black Child Savers is a stirring account of the stakes and meaning of social justice.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Black Child-Savers by Geoff K. Ward in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2012Print ISBN

9780226873183, 9780226873169eBook ISBN

9780226873190PART ONE

The Origins and Organization of Jim Crow Juvenile Justice

ONE

Citizen Delinquent: Race, Liberal Democracy, and the Rehabilitative Ideal

By the eighteenth century, Western liberal societies commonly regarded children and adolescents as uniquely malleable human beings whose individual developmental potential held a distinct significance for societal fates.1 Mainstream civic leaders generally believed that children, unlike adults, possessed the capacity to be trained or tailored to fit social norms and expectations. Child development thus required shaping and molding a normal, productive, and mature citizen before the rigidity of adulthood set in. Owing to the cultural and political link between child development and social welfare, juvenile social control became a concern for various, often competing constituencies interested in shaping the nation. That link was central to the republican idealism of early American juvenile justice, the development of Jim Crow juvenile justice, and the nearly century-long struggle to advance racial democracy within and through juvenile social control. This chapter surveys how the juvenile delinquent came to be understood as an “embryonic citizen,” whose fate was, perhaps, forever linked with the racial politics of American democratic ideals, movements, and institutions.

The Child, the Delinquent, and the State

The origins and significance of childhood as a life-course distinction in Western societies has been the subject of great interest and debate.2 Since at least the eighteenth century, cultural and legal concepts of childhood have been used to regulate social and political relations. The premise was that child development was in the interest of social welfare and, thus, a responsibility of the family and the parental state.

Early historiographies of childhood in Western European societies emphasize how the cultural and political distinction of the child evolved. Modern conceptions of childhood, they contend, first emerged in the sixteenth century. Before that, children were considered small people and ignored in developmental terms. In the West, only with the decline in infant mortality, the rise of Christianity, increased literacy, and industrialization and urbanization did children begin to be distinguished developmentally. With children and adolescents viewed as distinctly malleable beings, their development into adulthood had great cultural, economic, and political consequences. As the focus of increased concern, children’s socialization experiences became more regulated.3

Among the earliest and most influential evolutionary studies was Centuries of Childhood. In it, the French sociologist Philippe Ariès claims that modern society has progressed “from ignorance of childhood” through the Middle Ages “to the centering of the family around the child in the nineteenth century.” Examining children and families in the iconography of French art, architecture, religion, education, and other fields, Ariès maintains that modern conceptions of family life first surface in the sixteenth century and are common by the seventeenth.4 He and others explain the eventual recognition of childhood as a critical distinction in human development and civil status via demographic and social-organizational developments. Up to the Middle Ages, they maintain, high rates of infant mortality discouraged parents from becoming emotionally attached to offspring; these temporary sources of pleasure and joy were worthy of little sentimental and developmental investment. By the seventeenth century, as rates of infant and overall mortality continued to decline in the West, children were recognized as “potential adults” and beings who might come of age to participate in familial and social affairs. Given this possibility, children represented the future of the familial and societal unit. Parents and religious and secular civic leaders thus took increased interest in ensuring that these malleable beings would “be shaped and molded and formed into righteous, law-abiding, [and] God-fearing adults.”5

Industrialization and urbanization also changed family dynamics and the status differentiation of children. By the eighteenth century, many teenagers were considered adults. In their primarily rural milieu, they often lived independently of their parents, performed similar labor, and led new families with children of their own. Previously, low levels of education and similar capacities to perform agricultural labor contributed to a lack of distinction between young and old; lack of contact with other people’s children in rural environments limited concern about their control. Yet growing literacy rates provided a new basis for age-related developmental and status differentiation. Industrialization, urbanization, and the emerging market economy moved work outside the home, increased competition for labor and relevant skills, and brought young and old into contact and conflict in cities. Free young people grew more dependent on parents and for longer periods, becoming a greater concern in urban areas as the decline of informal controls seemed to increase the threat of dislocated youths. Adolescence was seen as an advanced stage of childhood, the final bridge to adulthood where the possibility for “normalization” through education and other interventions was diminishing and urgent. Adulthood lurked ominously as a point where the child-adolescent “could no longer be changed and would become set in [his or her] ways.”6

More recent histories challenge aspects of the evolutionary account of childhood; they do see a growing urgency to regulate child development by the end of the eighteenth century. Relying on more direct sources of parent and adult orientations toward children, such as diaries, biographies, and institutional records, these critics demonstrate that some of the allegedly modern conceptions of childhood existed in the Middle Ages and that children were not regularly objectified and brutalized before the modern era. The evidence suggests that parents have for all known time identified and loved their children, in ways that are more consistent with than distinct from modern conceptions but that defy generalization within and across societal contexts.7

Critics of the evolutionary view acknowledge changes in the cultural and political conceptions of childhood and related child-welfare practices by the eighteenth century. Such changes are crucial for understanding the general and racial politics of emerging juvenile justice systems. The historian Linda Pollock observes, for example, an “increased emphasis on the abstract nature of childhood and parental care from the seventeenth century onwards.” Beyond documenting events of misbehavior and punishments in response, she finds that parents’ diaries are increasingly consumed with general “methods of discipline” and the “duties of parents to children” and, ultimately, society. By the eighteenth century, parents were increasingly concerned with the civic utility of child discipline and their accountability for “ ‘training’ a child in order to ensure that he or she absorbed the correct values and beliefs and would grow into a model citizen.” Faced with this blended concept of child and social welfare, she found eighteenth-century mothers and fathers increasingly “approaching parenthood with apprehension and trepidation, worrying whether their modes of child care were correct, and whether they were sufficiently competent to rear their children.”8

Despite overstating the novelty and generalizable quality of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century sociolegal conventions related to families and children in Europe, Ariès’s sociological and political insights help account for the development and application of child-welfare reform strategies. The key novelty of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, he suggests, is not the formal appreciation of childhood as a stage of human development, but the cultural and institutional significance of the child relative to parents, families, and society. In particular, cultural conceptions of children as clay-like souls, the unsettled futures of family and society, and adult sensitivity to civic responsibility in raising children moved eighteenth- and nineteenth-century parents, and, in time, the parental state, to become more deliberately and coercively engaged with issues of child-welfare and juvenile social control.

By connecting the rise of modern society and the growing significance of the “family unit” and the “child” as status groups, Ariès uncovers the tightening of juvenile social control, a “contradiction in denying children their freedom, in the name of their own protection and moral education,” as Corsaro puts it.9 To an unprecedented extent, Ariès claims, a symbolic and constructive unity emerged in the idealized family. Between the medieval period and the seventeenth century, he argues, the child returned to the home, rather than being entrusted to apprenticeship relations, giving the seventeenth-century family its principal characteristic: the child “became an indispensable element of everyday life, and his parents worried about his education, his career, his future.”10

By the eighteenth century, then, the child’s importance grew in private families and public policy. Child welfare and discipline increasingly dominated concerns over success, not merely for individual children (or embryonic citizens), but for their familial and communal attachments. Spreading literacy, growing pressures of conformity and obedience, and the increasing presence of the state in regulating family life raised concerns with the civic utility of child discipline. This broadening of parental responsibility to ensure the proper socialization of children reflects Ariès’s notion of the growing significance of the private sphere in regulating social and political relations. “The modern family,” Ariès explained, “cuts itself off from the world and opposes to society the isolated group of parents and children.” In what clearly applies only to free adults and family units and especially to the more privileged among them, he continues: “All the energy of the group is expended on helping the children rise in the world, individually and without any collective ambition: the children rather than the family.”11 The founding justification for modern juvenile justice, and the logic of reform efforts since, has been that, if the more autonomous and apparently vital conjugal family failed in this child-socialization role, another regulatory apparatus, such as the parental state, would be needed to steer troubled youths into paths of self-discipline and social integration.

The Evil of Juvenile Delinquency

Changing cultural and political perspectives on childhood were not alone in the nineteenth-century development of novel concepts and systems of juvenile social control. Also critical were concerns about dependency and crime among young people and the development of a specific legal framework giving the state the regulatory authority to seek the normalization of child and adolescent attitudes and behaviors, when conjugal families could not. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, social changes including massive waves of European immigration, the rise of a market economy, the perceived inadequacy of informal controls in growing cities, and ideals of participatory democracy stoked the eagerness of societal elites to establish new laws and institutions to regulate child development.

Deviance has existed as long as social norms have, but the popularization of the concept of juvenile delinquency in Western societies can be traced to the late eighteenth century and the early nineteenth, when the United States and older Western European nations were transitioning from rural, agricultural societies to rising industrial powers.12 The Industrial Revolution and rapid urbanization inspired great excitement and fear; the new metropolis represented both a buffet of opportunity and adventure and a “place [where] scarcity, disease, neglect, ignorance, and dangerous influences” seemed equally abundant.13

Growing cities provided especially fertile ground for the rise of juvenile crime as a social problem and subject of popular and official concern. Rural family cohesion and work routines facilitated supervision of children and adolescents, but the Industrial Revolution disrupted family-centered controls. Urban labor markets distanced parents from idle children for longer periods of time, rendering older mechanisms of informal juvenile social control less effective. Population growth and change through urban internal migration and immigration resulted in larger proportions of juveniles in urban populations and increased community disorganization owing to greater crowding and unfamiliarity in neighborhoods. Urbanization also brought potentially delinquent youths into proximity with potential victims and agents of control. This pattern was of tremendous significance to juvenile justice in the twentieth-century black American experience as the Great Migration brought large numbers of black families to early, primarily urban, juvenile court communities. Well before then, however, movable goods and new relationships of ownership proliferated under industrialization and market capitalism, increasing the possibility of property crime and appeals for intervention. Manufacturers and merchants sought protection from theft through increased surveillance and the formal sanctioning of offenders, many of whom were youths.14

In the industrializing West, actual and perceived increases in juvenile crime and deviance drew a steady stream of concern in the first decades of the nineteenth century, the problem usually being attributed to a mix of social disorganization and the pathology of individuals and families in new urban centers. In 1816, for example, the First Survey of Juvenile Delinquency in London announced the discovery of “some thousands of boys under seventeen years of age in the metropolis who are daily engaged in the commission of crime.” The study’s authors blamed this growing “catalogue of criminals” on the neglectful conduct of parents, lack of education, lack of suitable employment, lack of religious observance, and “habits of gambling in the public streets.” The secondary sources of this “evil of Juvenile Delinquency” were said to include the “severity of the [criminal] code,” the “defective state of the police,” and the “existing system of prison discipline,” all of which either ignored or worsened the problem of delinquency. In Further Description of Juvenile Delinquency in London, a follow-up study conducted two years later, the authors still found it “painful to reflect that the remedy provided by the law should be one great cause of the evil”; they resolved that, for the youngest offenders at least, “absolute impunity would have produced less vice than confinement in almost any of the gaols in the Metropolis.”15 These critics were arguing, not that the state and concerned citizens should do nothing about juvenile delinquency, but rather that it was a novel problem requiring its own solution.

Much of delinquency’s novelty was attributed to the foreign element alleged to be common among young offenders. Similar to today’s rhetoric, a complex mix of genuine concern for public safety and child welfare, sensationalism, elitism, and xenophobia shaded portrayals of juvenile delinquents and appeals for their control across emerging industrial centers. In 1853, Charles L. Brace, the founder of New York’s Children’s Aid Society, characterized delinquents in that city as “mainly American-born, but the children of Irish and German immigrants . . . as ignorant as London flash-men [and] far more brutal than the peasantry from which they descend.” Rivaling the spectacular “superpredator” rhetoric of over a century later, Brace warned that menaces then were “ready for any offense or crime, however degraded or bloody,” and that, without normalizing infl...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Introduction: The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow Juvenile Justice

- PART I: THE ORIGINS AND ORGANIZATION OF JIM CROW JUVENILE JUSTICE

- PART II: REWRITING THE RACIAL CONTRACT: THE BLACK CHILD-SAVING MOVEMENT

- Conclusion: The Declining Significance of Inclusion

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Index