eBook - ePub

The Bourgeois Virtues

Ethics for an Age of Commerce

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

For a century and a half, the artists and intellectuals of Europe have scorned the bourgeoisie. And for a millennium and a half, the philosophers and theologians of Europe have scorned the marketplace. The bourgeois life, capitalism, Mencken's "booboisie" and David Brooks's "bobos"—all have been, and still are, framed as being responsible for everything from financial to moral poverty, world wars, and spiritual desuetude. Countering these centuries of assumptions and unexamined thinking is Deirdre McCloskey's The Bourgeois Virtues, a magnum opus that offers a radical view: capitalism is good for us.

McCloskey's sweeping, charming, and even humorous survey of ethical thought and economic realities—from Plato to Barbara Ehrenreich—overturns every assumption we have about being bourgeois. Can you be virtuous and bourgeois? Do markets improve ethics? Has capitalism made us better as well as richer? Yes, yes, and yes, argues McCloskey, who takes on centuries of capitalism's critics with her erudition and sheer scope of knowledge. Applying a new tradition of "virtue ethics" to our lives in modern economies, she affirms American capitalism without ignoring its faults and celebrates the bourgeois lives we actually live, without supposing that they must be lives without ethical foundations.

High Noon, Kant, Bill Murray, the modern novel, van Gogh, and of course economics and the economy all come into play in a book that can only be described as a monumental project and a life's work. The Bourgeois Virtues is nothing less than a dazzling reinterpretation of Western intellectual history, a dead-serious reply to the critics of capitalism—and a surprising page-turner.

McCloskey's sweeping, charming, and even humorous survey of ethical thought and economic realities—from Plato to Barbara Ehrenreich—overturns every assumption we have about being bourgeois. Can you be virtuous and bourgeois? Do markets improve ethics? Has capitalism made us better as well as richer? Yes, yes, and yes, argues McCloskey, who takes on centuries of capitalism's critics with her erudition and sheer scope of knowledge. Applying a new tradition of "virtue ethics" to our lives in modern economies, she affirms American capitalism without ignoring its faults and celebrates the bourgeois lives we actually live, without supposing that they must be lives without ethical foundations.

High Noon, Kant, Bill Murray, the modern novel, van Gogh, and of course economics and the economy all come into play in a book that can only be described as a monumental project and a life's work. The Bourgeois Virtues is nothing less than a dazzling reinterpretation of Western intellectual history, a dead-serious reply to the critics of capitalism—and a surprising page-turner.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Bourgeois Virtues by Deirdre Nansen McCloskey,Deirdre N. McCloskey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2010Print ISBN

9780226556642, 9780226556635eBook ISBN

97802265566731

THE VERY WORD “VIRTUE”

Bourgeois virtues? The question is whether virtues could be expected to flourish in our commercial society. Are there in fact bourgeois virtues? And what do they have to do with traditional talk about the virtues?

In 1946 the anthropologist Ruth Benedict wrote a book purporting to explain the ethical system of the Japanese to their former enemies. It perhaps said more, Clifford Geertz has noted, about a “look-into-ourselves-as-we-would-look-unto-others.”1 But never mind. With the substitution of “bourgeois” for “Japanese” her declaration of intent could serve here: “This volume . . . is not a book specifically about [bourgeois] religion or economic life or politics or the family. It examines [bourgeois] assumptions about the conduct of life. It describes these assumptions as they have manifested themselves whatever the activity in hand. It is about what makes [the bourgeoisie into an ethical one].”2

I’ll use the words “ethical” and “moral” interchangeably, though favoring “ethical.” In origin “ethical” is Greek and at the height of Greek philosophy leaned toward character and education, while “moral” is Latin and always leaned toward custom and rule. But this shadow of a difference was blurred even by the Greco-Roman moralists, and is not preserved in modern English, even in precise philosophical English. As happens often in our magpie English tongue, “ethical” and “moral” have became merely two words for the same thing, derived from different languages.

The newspapers restrict “ethics” to business practice, usually corrupt, and “morality” to sexual behavior, often scandalous. I opt for the ordinary, nonnewspaper usage that takes “morality” to be a synonym for “ethics,” which is to say the patterns of character in a good person. True, the words have become entangled in the red vs. blue states and their culture wars. The left once embraced situational ethics and the right favored a moral majority. Now the Christian and progressive left wonders at the ethics of capital punishment and the Christian and neocon right wonders at moral decline. But at the outset let us have peace.

“Ethics” is the system of the virtues. A “virtue” is a habit of the heart, a stable disposition, a settled state of character, a durable, educated characteristic of someone to exercise her will to be good. The definition would be circular if “good” just meant the same thing as “virtuous.” But it’s more complicated than that. Alasdair MacIntyre’s famous definition is: “A virtue is an acquired human quality the possession of which tends to enable us to achieve those goods which are internal to practices and the lack of which effectively prevents us from achieving such goods.”3

A virtue is at the linguistic level something about which you can coherently say “you should practice X”—courage, love, prudence, temperance, justice, faith, hope, for example. Beauty is therefore not a virtue in this sense of “exercising one’s will.” One cannot say, “You should be beautiful” and make much sense, short of the extreme makeover. Neat, clean, well turned out—yes. But not “beautiful.”

At the simplest level people have two conventional and opposed remarks they make nowadays when the word “ethics” comes up. One is the fatherly assertion that ethics can be reduced to a list of rules, such as the Ten Commandments. Let us post the Sacred List, they say, in our courthouses and high schools, and watch its good effects. In a more sophisticated form the fatherly approach is a natural-law theory by which, say, homosexuality is bad, because unnatural.4

In contrast, the other remark that people make reflects the motherly assertion that ethics is after all particular to this family or that person. Let’s get along with each other and not be too strict. Bring out the jello and the lemonade. In its sophisticated form the motherly approach is a cultural relativist theory that, say, female circumcision and the forced marriage of eleven-year-old girls are all right—because they are custom.5

The “virtue-ethic” parallel to such college-freshman commandments or college-sophomore relativism is the vocabulary of the hero and of the saint. In its senior high-school version the two split by gender, at least conventionally, and at least nowadays. A man wants to be Odysseus, a woman Holy Mary, the one physically courageous, the other deeply loving.

The sharpness of the gender split appears to be only a couple of centuries old. By 1895 Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., could declare that “the ideals of the past for men have been drawn from war, as those for women have been drawn from motherhood.”6 “War is for men,” said Mussolini some decades later, “what birth is for women.”7 Now at the beginning of the twenty-first century we still speak in our goodness talk mainly of courage and of love, the fatherly rhetoric of conservatives and the motherly rhetoric of liberals.8

The models are popular heroes and saints—Sergeant York was wonderfully courageous” or “Mother Teresa loved the poor”—and by analogy we praise the ordinary little virtues. We witness “Some village Hampden, that with dauntless breast / The little tyrant of his fields withstood,” and we applaud. A local boy endures a football injury, courageously. Brave boy. A young almost-bride mourning for her soldier walks up and down, up and down, in her stiff brocaded gown, and we weep. A local girl volunteers at the retirement community, lovingly. Sweet girl.

Such talk is on its way to the virtues. But it’s still high-school stuff. We can do better, getting all the way to graduate school, by being a little more philosophical. In particular we can enfold the street talk of manly courage and womanly love, fatherhood and motherhood, into the seven virtues of the classical and Christian world. This is my main theme. To the natural-law and cultural-relativist theorists we can reply that virtues underlie their theories, too, and that the virtues are both less and more universal than they think. That’s what I propose to do, and then show you that a bourgeois, capitalist, commercial society can be “ethical” in the sense of evincing the seven.

The virtues came to be gathered by the Greeks, the Romans, the Stoics, the church, Adam Smith, and recent “virtue ethicists” into a coherent ethical framework. Until the framework somewhat mysteriously fell out of favor among theorists in the late eighteenth century, most Westerners did not think in Platonic terms of the One Good—to be summarized, say, as maximum utility, or as the categorical imperative, or as the Idea of the Good. They thought in Aristotelian terms of many virtues, plural.

“We shall better understand the nature of the ethical character [to ethos],” said Aristotle, “if we examine its qualities one by one.”9 That still seems a sensible plan, and was followed by almost all writers on ethics in the West, and quite independently of Aristotle in the East, until the cumulative effect of Machiavelli, Bacon, Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau, Kant, and Bentham at length killed it off. Thus Edmund Spenser in The Faerie Queen (1596) celebrated in six books Holiness, Temperance, Chastity, Friendship, Justice, and Courtesy.

Since about 1958 in English a so-called “virtue ethics”—as distinct from the Kantian, Benthamite, or contractarian views that dominated ethical philosophy from the late eighteenth century until then—has revived Aristotle’s one-by-one program. “We might,” wrote Iris Murdoch in 1969 early in the revival, “set out from an ordinary language situation by reflecting upon the virtues . . . since they help to make certain potentially nebulous areas of experience more open to inspection.”10 That seems reasonable.

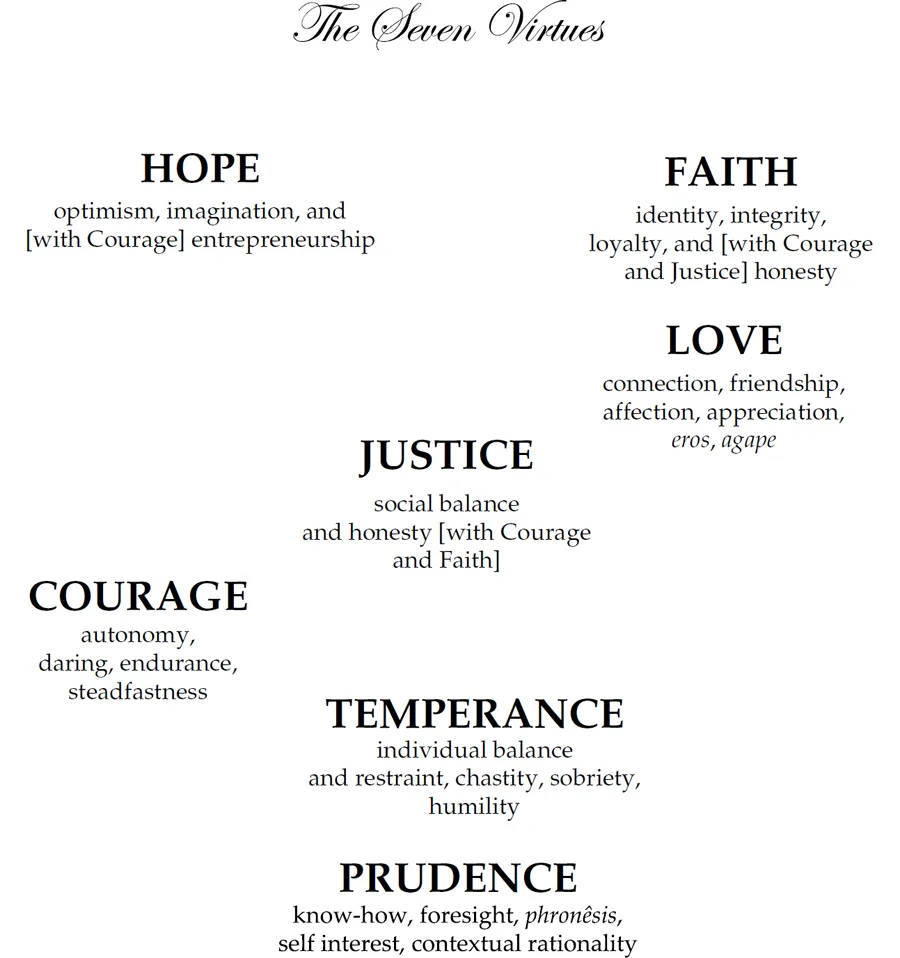

Here are the Western seven, with some of their subvirtues appended. The system is a jury-rigged combination of the “pagan” virtues appropriate to a free male citizen of Athens (Courage, Temperance, Justice, and Prudence) and the “Christian” virtues appropriate to a believer in Our Lord and Savior (Faith, Hope, and Love).

Jury-rigged or not, the seven, I will argue, cover what we need in order to flourish as human beings. So also might other ethical systems—Confucianism, for example, or Talmudic Judaism, or Native American shamanism—and these can be lined up beside the seven for comparison. There are many ways to be human. But it is natural to start and for present purposes pretty much finish with the seven, since they are the ethical tradition of a West in which bourgeois life first came to dominance.

2

THE VERY WORD “BOURGEOIS”

Bourgeois virtues? Consider then that first word. Yes, we are bourgeois, we educated folk, not aristocratic or proletarian. We are businesspeople or bureaucrats, not kings or peasants. Yet for a century and a half now the word has been a sneer, as in “Oh, Daddy, you’re so bourgeois!” or in Leadbelly’s song “Bourgeois Town”:

These white folks in Washington, they know how:

Treat a colored man just to see him bow.

Lawd, in a bourgeois town,

Hee! it’s a bourgeois town.

I got the bourgeois blues, gonna spread the news all around.1

At one time in French bourgeois meant without contempt merely “townsman-ly,” from a Germanic (not Latin) word for a walled town. It shows up in Edinburgh and the New York borough of Queens and, with Latin latro added on, a burglar, a thief preying on the town. It came itself from an Indo-European root, meaning “high.” So “belfry” from the Old French berfrei, a high place of freedom from attack. The tribe of Burgundi came from the high country of Savoy. The Norse berg, “mountain,” appears in Bergen, literally “the mountain,” and ice berg. All of the Germanic words, it says here in The American Heritage Dictionary of Indo-European Roots, revised and edited by Calvert Watkins, are cousins through their Proto-Indo-European grandparents with Latin words in fort-, such as “fort” and “fortitude,” or any strength.

Anyway bourgeois (boor-zhwa) is the adjective, describing Daddy, say, or the Long Island suburbs. It’s also in the French the noun for the singular male person, a burgher. Benjamin Franklin was “a bourgeois.” And strictly speaking in French, though odd-sounding in English, the plural men of the middle class go by the same word, those bourgeois trading news on the Bourse. The female burgheress, singular, adds an e, bourgeoise (boor-zhwaz). Madame Bovary was a bourgeoise, and she and her friends bourgeoises, plural, with again no change in pronunciation. The whole class of such people are of course that appalling bourgeoisie (boor-zhwa-zee), whence H. L. Mencken’s sneering label, the “booboisie.”

Got it.

But consider this: in sociological fact you are probably a member of it. You may therefore still be using the word as a term of self-contempt, like the f-word for gays or the n-word for blacks. As Mencken also said, the businessman “is the only man who is forever apologizing for his occupation.”2

After the Second World War the self-scorning of the middle class became a standard turn among even the non-Marxist clerisy, from C. Wright Mills to Barbara Ehrenreich. Ehrenreich wrote in Fear of Falling: The Inner Life of the Middle Class (1989) of the bourgeoisie’s “prejudice, delusion, and even, at a deeper level, self-loathing.”3 She would know about the self-loathing. Her father started as a copper miner (Ehrenreich was born in Butte) but became a corporate executive. She herself got a Ph.D. in biology, but was radicalized by Vietnam. So was I, incidentally, before my Ph.D. in economics took hold.

Self-loathing among the bourgeoisie has for a century and a half been a source of trouble. We need to rethink together the word and the social position. Guilt over success in a commercial society is for a victimless crime. Yet the children of the bourgeoisie seek an identity challenging that of their elders. The clerisy by which the children are taught accuses the middle class of inauthenticity, and plays on pseudoaristocratic contempt for “middle” construed as “mediocre.” None of this makes very much sense. A commercial life can be as authentic and virtuous as that of a philosopher or priest. We need to recover its wholeness and holiness.

A reason to keep here the dishonored word “bourgeois” is to distinguish the rethinking from the statistical inquiries evoked by “middle class,” or the older “middling sort.” My focus is not mainly on how large the middle class actually...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Apology: A Brief for the Bourgeois Virtues

- Appeal

- Epilogue

- 1. The Very Word “Virtue”

- 2. The Very Word “Bourgeois”

- 3. On Not Being Spooked by the Word “Bourgeois”

- Part 1: The Christian and Feminine Virtues: Love

- Part 2: The Christian and Feminine Virtues: Faith and Hope

- Part 3: The Pagan and Masculine Virtues: Courage, with Temperance

- Part 4: The Androgynous Virtues: Prudence and Justice

- Part 5: Systematizing the Seven Virtues

- Part 6: The Bourgeois Uses of the Virtues

- Postscript: The Unfinished Case for the Bourgeois Virtues

- Notes

- Works Cited

- Index