- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Although plants comprise more than 90% of all visible life, and land plants and algae collectively make up the most morphologically, physiologically, and ecologically diverse group of organisms on earth, books on evolution instead tend to focus on animals. This organismal bias has led to an incomplete and often erroneous understanding of evolutionary theory. Because plants grow and reproduce differently than animals, they have evolved differently, and generally accepted evolutionary views—as, for example, the standard models of speciation—often fail to hold when applied to them.

Tapping such wide-ranging topics as genetics, gene regulatory networks, phenotype mapping, and multicellularity, as well as paleobotany, Karl J. Niklas's Plant Evolution offers fresh insight into these differences. Following up on his landmark book The Evolutionary Biology of Plants—in which he drew on cutting-edge computer simulations that used plants as models to illuminate key evolutionary theories—Niklas incorporates data from more than a decade of new research in the flourishing field of molecular biology, conveying not only why the study of evolution is so important, but also why the study of plants is essential to our understanding of evolutionary processes. Niklas shows us that investigating the intricacies of plant development, the diversification of early vascular land plants, and larger patterns in plant evolution is not just a botanical pursuit: it is vital to our comprehension of the history of all life on this green planet.

Tapping such wide-ranging topics as genetics, gene regulatory networks, phenotype mapping, and multicellularity, as well as paleobotany, Karl J. Niklas's Plant Evolution offers fresh insight into these differences. Following up on his landmark book The Evolutionary Biology of Plants—in which he drew on cutting-edge computer simulations that used plants as models to illuminate key evolutionary theories—Niklas incorporates data from more than a decade of new research in the flourishing field of molecular biology, conveying not only why the study of evolution is so important, but also why the study of plants is essential to our understanding of evolutionary processes. Niklas shows us that investigating the intricacies of plant development, the diversification of early vascular land plants, and larger patterns in plant evolution is not just a botanical pursuit: it is vital to our comprehension of the history of all life on this green planet.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Plant Evolution by Karl J. Niklas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Ecology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2016Print ISBN

9780226342146, 9780226342009eBook ISBN

97802263422831

Origins and Early Events

On looking a little closer, we find that inorganic matter presents a constant conflict between chemical forces, which eventually works to dissolution; and on the other hand, that organic life is impossible without continual change of matter, and cannot exist if it does not receive perpetual help from without.

—ARTHUR SCHOPENHAUER, Parerga und Paralipomena (1851)

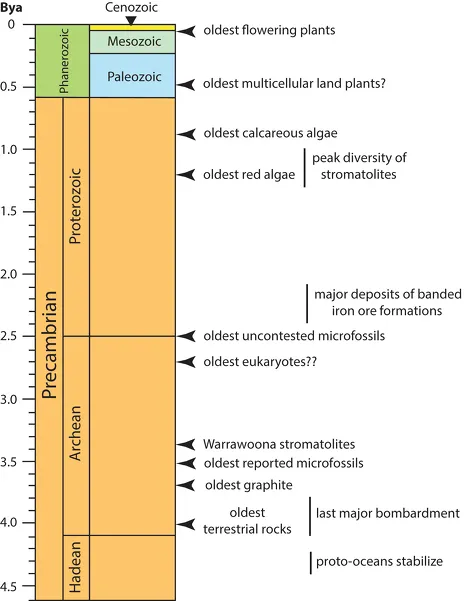

This chapter begins our exploration of plant evolution with an outline of plant history and a focus on broad physiological and morphological innovations. This outline is difficult to sketch because the history of plant life is extremely complex and begins with the evolution of the first living things, estimated to be as old as 3.6 billion years (fig. 1.1). Nevertheless, eight events in the history of plant life loom as monumental in their consequences on all forms of life. These are (1) the evolution of the first cellular forms of life, (2) the origin and development of photosynthetic cells, (3) the evolution of multicellularity in prokaryotic microorganisms, (4) the first appearance of eukaryotic cells (organisms with organelles and the capacity of sexual reproduction), (5) the ecological assault of plants on land and their growth in air, (6) the evolution of conducting tissues, (7) the evolution of the seed habit, and (8) the rise of the flowering plants. The first four of these events are treated in this chapter. The last four are treated in the chapter 2. The division is somewhat arbitrary, since history is a continuous process. However, the eight events selected for review are arranged in chronological order, and partitioning them into two equal-sized groupings is parsimonious.

Figure 1.1. A schematic of the geological column showing its chronology in billions of years (to the left) and highlighting some major evolutionary events (to the right). The vast majority of the geological column is occupied by the Precambrian, and many of the most important historical events are recorded in this span of time. For example, the origins of living things are indicated by the oldest known deposits of graphite and stromatolites. The major deposits of banded (oxidized) iron ores indicate the presence of free oxygen (and thus the evolution of photosynthesis). The appearance of the red algae in the fossil record is evidence for the evolution of multicellular eukaryotic organisms, and the fossil remains of land plants indicate that these organisms evolved features that permitted growth in the air. It is important to bear in mind that the oldest evidence for any of these evolutionary events is likely not the earliest appearance of these features since future discoveries may reveal still older occurrences.

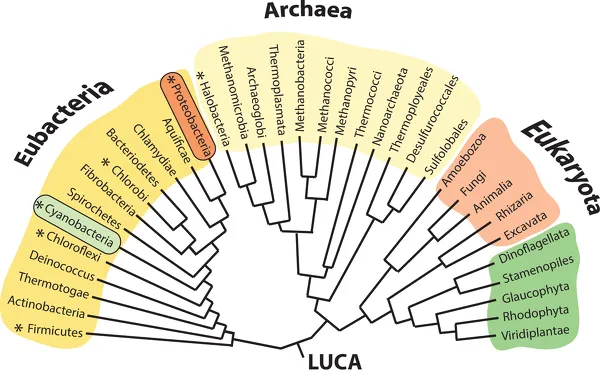

Compared with the origins of life, subsequent historical events may seem pale. But each of the eight major events is of comparable importance to life’s story because without them the world as we know it would not exist. Perhaps the most obvious of these events is the evolution of metabolism (such as photosynthesis, the chemically intricate process that converts light energy into chemical energy). Living things are characterized by having the ability to process energy and matter in ways that permit them to survive, grow, and reproduce. Some of life’s basic and generalizable metabolic systems are the pentose phosphate pathway, glycolysis, and photosynthesis. In one way or another, nearly all forms of life depend on these processes. For example, the evolution of photosynthetic organisms, particularly those that release oxygen as a by-product, dramatically changed the physical and biological environment of the ancient Earth (box 1.1). Equally important to the history of all life was the evolution of cells containing the microscopic membrane-bound objects called organelles, whose internal structure and chemical composition are highly specialized to participate in life’s various biochemical and genetic processes. The absence or presence of organelles in cells divides all living things into two great organic camps: the prokaryotes, organisms whose cells lack organelles, and the eukaryotes, whose cells contain them. The prokaryotes comprise two large and distinctively different groups of prokaryotes—the Archaea and the Eubacteria (fig. 1.2). The eukaryotes encompass all other forms of life—plants, animals, and fungi. The prokaryotes are the more ancient and undoubtedly the more physiologically resilient and ecologically successful forms of life. Current evolutionary theory states that the first eukaryotes evolved from ancient loose symbiotic confederations of prokaryotic-like forms of life. Thus, the “great organismic wedge” between prokaryotes and eukaryotes was not as sharply defined in the distant past as it is now. Indeed, many prokaryotes manifest a process called pseudo-sexuality in which genetic materials are exchanged between neighboring cells in a seemingly disorganized manner. As in the case of eukaryotes, the introduction of novel genetic information into prokaryotic populations relies on chance mutations.

Figure 1.2. Schematic showing the broad phylogenetic relationships among the prokaryotes (Eubacteria and Archaea) and the eukaryotes (Eukaryota consisting of algae, plants, animals, and fungi) that descended from a last universal common ancestor (LUCA). The cyanobacteria and the proteobacteria are highlighted because, according to the endosymbiotic theory, cyanobacteria-like and proteobacteria-like organisms respectively evolved into modern day chloroplasts and mitochondria. Clades within the Eubacteria and Archaea that have photosynthetic representatives are denoted by an asterisk.

Organisms capable of sexual reproduction likely appeared collaterally with or shortly after the first eukaryotes evolved, although some believe a significant time gap exists between these two events. What can be said with certainty is that sexual reproduction (as defined with eukaryotes in mind) required the evolution of meiosis, the “two stage” type of cell division producing cells with half the chromosome number of the cells from which they arise. Meiosis results in genetic recombination, whose evolutionary consequences are treated in chapter 3. The eukaryotes can mix and blend the traits of different parents through sexual reproduction and meiosis. Although it is somewhat surprising, biologists continue to debate the importance of sexual reproduction to evolution, and there is no general agreement about the benefits conferred on organisms by genetic recombination (we will explore this topic again in chapters 3 and 7). The bacteria continue to be the most successful forms of life without benefit of sexual reproduction, but genetic recombination continues to be an effective way of adapting organisms to new habitats and adopting new and different forms of biological organization. Sexual reproduction and the sequestration of reproductive cells from somatic cells may have evolved to deal with the decreasing mutation rates associated with increasing organismic size. Larger organisms reproduce at a slower rate than smaller organisms, but they tend to accumulate genetic mistakes the more times cells divide. Arguably, the isolation of reproductive cells (the germ line) from somatic cells, meiosis, and sexual reproduction may have been required to engender sufficient genetic variation as the number of mutations increased in proportion to the increasing body size of eukaryotes. The isolation of a germ line with a concomitant reduction in cell divisions would also have reduced the accumulation of potentially deleterious genetic anomalies in reproductive cells. (This topic is taken up in chapter 6, wherein we will also discuss the possibility that meiosis may have also evolved before sexual reproduction as a method of correcting for the spontaneous doubling of chromosome numbers, called autopolyploidy.) What can be said without doubt is that the appearance of unicellular eukaryotes presaged multicellular organisms and the evolution of the most visibly conspicuous forms of aquatic and terrestrial life.

Life’s Beginnings

Precisely how life began is still a mystery, particularly since the prevailing conditions of the early Earth were inimical to life as we know it today. The embryonic Earth was a protoplanet devoid of atmosphere, cracked by volcanic upheaval and lightning, flooded by lethal ultraviolet light, and rained on by the rocky debris of a juvenile solar system still actively in the violent process of birth—a world whose original surface was molten rock and whose first atmosphere, largely composed of hot hydrogen gas, was vented into space almost as quickly as it emerged from the Earth’s radioactive core. Although hard to conceive of, these were the conditions when Earth formed roughly 4.6 billion years ago (see fig. 1.1). Earth’s first age is called the Hadean, reflecting the netherworld status of our juvenile planet. Nonetheless, with the passage of a comparatively short time, Earth’s version of Hades cooled sufficiently to retain the first proto-oceans formed from torrential rains when water condensed in the atmosphere. Earth continued to be bombarded by fragments of a still forming solar system, and, although possibly diminished, sources of energy like lightning, volcanoes, and ultraviolet light continued to inspire molecular upheaval, breaking and forming molecular bonds in the atmosphere and the shallow proto-oceans.

On the basis of the gases vented from currently active volcanoes, Earth’s early atmosphere likely consisted of a mixture of water vapor, carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, nitrogen, methane, and ammonia, but its precise composition is still debated. Most textbooks categorically state that Earth’s first atmosphere was a strongly reducing one, in large part because the first successful laboratory experiments to abiotically synthesize organic molecules used a strongly reducing atmosphere (see below) and because the energies required to abiotically synthesize simple organic molecules like amino acids from raw ingredients such as carbon dioxide and ammonia are much lower in a strongly reducing atmosphere (such as one composed of methane, ammonia, water vapor, and hydrogen) than in a strongly oxidizing one (composed of carbon dioxide, water vapor, nitrogen, and oxygen). Nevertheless, it is worth noting that geochemical and astronomical evidence opens the possibility that the ancient atmosphere was not as reducing as formerly believed but may have been very much like that of today without, naturally, the effects of life (an atmosphere dominated by N2 and CO2, with a small ration of noble gases along with some H2 and CO).

For convenience, we will discuss the continuous evolution of early life in four stages:

(1) The accumulation of abiotically synthesized small organic molecules (monomers) such as amino acids and nucleotides.

(2) The abiotic joining of these monomeric chemicals into polymers such as proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids.

(3) The origin of the heredity molecules ribonucleic acid (RNA) and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA).

(4) The aggregation of abiotically synthesized molecules into cell-like membrane-bound droplets (called protobionts) that had an internal chemical environment differing from the external chemical environment.

Notice that evolution technically does not enter into the first two stages because evolution requires heritability that in turn requires heredity molecules. Although some may talk about “the evolution of the solar system” or “the evolution of the Earth’s atmosphere,” the use of the word “evolution” in these contexts must be perceived as having a different meaning from that of a biologist’s.

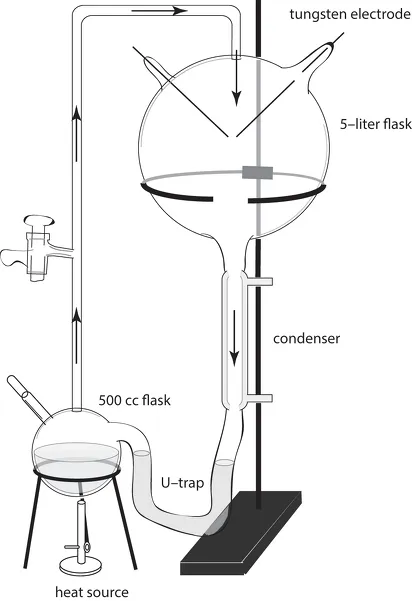

Of these four stages, the first is the most easily simulated in the laboratory. Organic monomers can be abiotically synthesized with comparative ease using a variety of energy sources and a range of atmospheric compositions believed to mimic early Earth conditions. This simulation was first widely publicized with the landmark experiments in 1952 of Stanley L. Miller (1930–2007) and Harold Urey (1893–1981), who created a strongly reducing “mock” atmosphere of water vapor, hydrogen gas, methane, and ammonia (probably too strongly reducing, according to recent thinking) suspended over a mock ocean of heated water (fig. 1.3). After continuously subjecting the atmosphere to an electrical discharge using tungsten electrodes (to simulate lightning), Miller and Urey chemically analyzed the aquatic residue in their experimental system and found a variety of organic compounds (fig. 1.4). The most abundant of these was glycine, a common amino acid. Additionally, many of the other standard twenty amino acids were identified, although in lesser amounts than glycine (box 1.2). Subsequent experiments using different recipes for Earth’s ancient atmosphere have abiotically synthesized several sugars and lipids as well as the compounds generated in the original Urey-Miller experiment. Equally important was the discovery that the purine and pyrimidine bases found in RNA and DNA can also be synthesized under comparatively mild chemical conditions and by simulating the extraordinarily violent effects of asteroid collisions with earth. Also, when phosphate was added to a mock ocean, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) could form spontaneously. ATP is the major energy-transferring molecule in living cells. The demonstration of the abiotic synthesis of ATP under conditions mimicking those of early Earth is important to any theory of the origin of life.

Figure 1.3. Schematic of the reaction vessel and ancillary equipment used in the Urey-Miller experiments. Distilled water was placed in a 500 cc flask that was heated to release water vapor that was cycled into a 5 liter flask containing a mixture of gases mimicking Earth’s ancient reducing atmosphere. The gas mixture (water, methane, ammonia, and hydrogen) was exposed to continuous electrical discharge by means of two tungsten electrodes to mimic lightening. The chemical reactants occurring in the atmosphere precipitated as “rain” and were collected in a U-trap. The arrows placed in various parts of the schematic show th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- CONTENTS

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1 Origins and Early Events

- 2 The Invasion of Land and Air

- 3 Population Genetics, Adaptation, and Evolution

- 4 Development and Evolution

- 5 Speciation and Microevolution

- 6 Macroevolution

- 7 The Evolution of Multicellularity

- 8 Biophysics and Evolution

- 9 Ecology and Evolution

- Glossary

- Index