- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

National identity and political legitimacy always involve a delicate balance between remembering and forgetting. All nations have elements in their past that they would prefer to pass over—the catalog of failures, injustices, and horrors committed in the name of nations, if fully acknowledged, could create significant problems for a country trying to move on and take action in the present. Yet denial and forgetting carry costs as well.

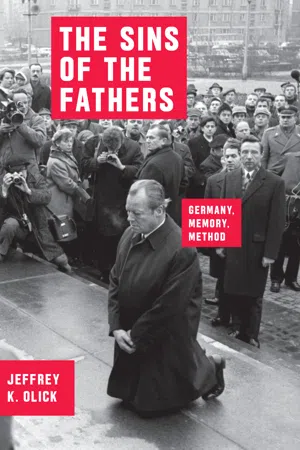

Nowhere has this precarious balance been more potent, or important, than in the Federal Republic of Germany, where the devastation and atrocities of two world wars have weighed heavily in virtually every moment and aspect of political life. The Sins of the Fathers confronts that difficulty head-on, exploring the variety of ways that Germany's leaders since 1949 have attempted to meet this challenge, with a particular focus on how those approaches have changed over time. Jeffrey K. Olick asserts that other nations are looking to Germany as an example of how a society can confront a dark past—casting Germany as our model of difficult collective memory.

Nowhere has this precarious balance been more potent, or important, than in the Federal Republic of Germany, where the devastation and atrocities of two world wars have weighed heavily in virtually every moment and aspect of political life. The Sins of the Fathers confronts that difficulty head-on, exploring the variety of ways that Germany's leaders since 1949 have attempted to meet this challenge, with a particular focus on how those approaches have changed over time. Jeffrey K. Olick asserts that other nations are looking to Germany as an example of how a society can confront a dark past—casting Germany as our model of difficult collective memory.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Sins of the Fathers by Jeffrey K. Olick in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Geschichte & Deutsche Geschichte. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

* Part 1 *

Introduction

Chapter 1

Placing Memory in Germany

On November 10, 1988, the West German parliament assembled for a rare special commemorative session. Fifty years earlier, Nazi thugs had systematically rampaged through the streets of German cities and towns.1 With the bogus justification that a Jew had assassinated a German official in Paris, they looted, burned, and otherwise vandalized German-Jewish businesses, homes, and places of worship, arresting many Jews, beating and killing others. Official anti-Semitism was certainly not new in 1938 Germany, but the events of the so-called Kristallnacht (Night of Broken Glass) were a portentous demonstration of the regime’s brutal hatreds and violent potential. No longer could ordinary Germans honestly dismiss National Socialist rhetoric as a mere tactic or deny its human consequences. While perhaps nothing before the Holocaust could have led one to imagine such an eventuality, in retrospect (even noting all the distortions of hindsight) Kristallnacht appears as a major moment in an historical trajectory consummated in the gas chambers.2 Fifty years later, its anniversary provided an important opportunity for West Germany to symbolize its distance from that world long past.

The ninth of November in 1938 was not, of course, the only one marked in German history. November 9 was also the anniversary of the revolution of 1918, as well as that of the “Beer Hall Putsch” of 1923; in 1989 it would be the day the Berlin Wall opened. Nor was 1988 the first time the events of 1938 had been commemorated in West Germany, though it was the first time that such a commemoration was to be stamped with the import of a ceremony in the Bundestag. Indeed, the previous few years in the Federal Republic had seen a number of important debates about the meaning of the Nazi past, and this 1988 commemoration of Kristallnacht succeeded several notable fortieth anniversaries of other events and preceded a flurry of fiftieths. However singular, commemorative events are always but moments in continually unfolding stories, and the context of the 1988 Kristallnacht ceremony included ongoing controversies about the present and future role of commemoration in German politics.

While the governing Christian Democrats3 had originally opposed a special commemorative session of the parliament for the occasion, East German plans for a major ceremony led the West German conservatives to acquiesce to opposition proposals. One lesson of the contentious debates of the previous years—indeed, of the entire history of the Federal Republic—was that the West German leadership could not appear unwilling to acknowledge the Nazi past, to say nothing of letting the East Germans seem more willing to do so. But the Christian Democrats did not go so far as to accept a proposal of the Green Party, supported by a number of Social Democrats, to invite Heinz Galinski, chairman of the Central Council of Jews in Germany (Zentralrat der Juden in Deutschland), to speak. The Christian Democratic president of the Bundestag, Philipp Jenninger, wanted very much to deliver a major address, aspiring to match Federal President Richard von Weizsäcker’s worldwide triumph three years earlier, on the fortieth anniversary of May 8, 1945, the day of Germany’s surrender.4 Despite the wrangling, Jenninger had every expectation of success. He was an experienced—and previously unchallenged—speaker about the Nazi past, was well respected as a politician and leader, and was seeking to extend rather than to question the critically acclaimed commemorative solutions von Weizsäcker had offered in 1985.

The 1988 ceremony opened with a song, featuring cantor and chorus, from the Kracow Ghetto Notebook by Yiddish poet Mordechai Gebirtig, followed by the Jewish actress Ida Ehre reading the poet Paul Celan’s “Todesfuge.” Jenninger then began his address: “Today we have come together in the Bundestag because not the victims, but rather we, in whose midst the crimes occurred, must remember and give an accounting for what we did; because we Germans want to come to an understanding of our past and of its lessons for our present and future politics.” Almost immediately, the catcalls began. Jenninger pleaded that he be allowed to continue, that “this dignified moment” be allowed to take place in its planned form. As he tried desperately to continue and grew ever more flustered, however, the challenges increased. Members of the Bundestag began to leave the chamber in protest. Others remained transfixed in their seats, some covering their faces with their hands. As Jenninger pushed ahead to detail the hopes and failures of “ordinary Germans” in the 1930s, one of the most spectacular disasters in the history of German commemoration unfolded. Within hours of the ceremony, Jenninger submitted his resignation and retreated from public life.5

Outraged cries asking how this could have happened quickly gave way to more perplexed questions about what exactly had occurred. The deputies who had stormed out of the chamber expressed their outrage, but were hard pressed to specify what had caused it. As hours turned into days and weeks, commentators reflected on the actual text of Jenninger’s speech, and began wondering what had gone wrong. Jenninger had said nothing substantively new about German history, nothing others had not already said in other contexts, though he had addressed German motivations in an unusually direct manner.6 It was members of the Greens and of the Social Democrats who left the chamber—not conservatives, who were more commonly associated with avoiding direct attention to German perpetration (though the left was always more likely to condemn what it saw as inadequate commemoration). But even Jenninger’s own party wasted no time accepting his resignation, and did not challenge the challenge: they were eager to show that they had learned the lessons of three years earlier, when US President Ronald Reagan and West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl had faced severe criticism for appearing to wipe out historical differences during a wreath-laying ceremony at a military cemetery at Bitburg.7 Within several weeks, a loose consensus emerged that although something here had gone seriously wrong, it was not necessarily Jenninger’s fault, his poor oratorical performance aside.8

The Problems of the German Past

The Jenninger scandal is but one moment in the extraordinarily complex history of German public memory. Many pages from now in this book, I offer a richer description of the event itself, and venture a reading of it. Here, the anecdote serves merely to sensitize us to the difficult issue of German commemoration: one pitted with mixed motives, conflicting demands, and vexed themes even fifty years on. How do you speak for a nation held accountable not only for two devastating wars in one century, but for what many consider to be the worst atrocity in human history? This is the dilemma every leader of the Federal Republic of Germany has faced.9 To explain the solutions they have offered is this book’s central goal.

All nations, of course, have specific parts of their collective pasts they would prefer to pass over. The catalogue of failures, injustices, and horrors committed in the name of nations can create significant problems if openly acknowledged. National identity and political legitimacy always involve a precarious balance between remembering and forgetting. But nowhere has this problem been more potent than in the Federal Republic of Germany, where a difficult past has weighed heavily in virtually every moment and aspect of political life. As other nations face historical burdens from their past, moreover, they often look to Germany as a test of what happens when a society confronts difficult memories. Germany, one might say, has become the world’s canary in the mine of historical consciousness, and our benchmark of spoiled identity.10

Specifying the German Past

But why has the past been a problem for German politicians? The answer seems obvious: It is because of the Holocaust. Saying this, however, raises more questions than it answers. For instance, “Holocaust” is not an unproblematic term: it already implies an interpretation, one different in sometimes important ways from other terms such as “Shoah,” “Final Solution,” or “Genocide of the European Jews.” Each of these terms—as well as others—has its own history and its own distinctive historical, political, and even theological implications (see, for instance, Young 1988). This book is in part an examination of the origins and operations of these and other meanings in the German discourse. Obviously, some term is necessary for expository purposes, and I will indeed mostly use “Holocaust” (capitalized as the name of an event rather than being lowercased as a metaphorical description) because it is the term most commonly used in the historical literature and in popular culture. By doing so, however, I am not explicitly endorsing any particular interpretation—historical, political, or theological. Mostly, I am interested in which words Germans used with what implications. “Holocaust,” as we will see, was a relative latecomer to the German discourse.

This fact leads directly to another important caveat to seeing the Holocaust as the obvious problem for German politicians. As Tony Kushner puts it,

Historians and others have an enormous desire to believe that the liberation of the camps in spring 1945 exposed to the world the horrors of the Holocaust. In so doing they impose later perceptions on contemporary interpretations and provide a deceptively simple chronology on what was, in reality, a prolonged and complex process which is yet to be completed. The assumption that an immediate connection was made at the time of the liberation of the camps to what is known as the horrors of the Holocaust has rarely been checked by reference to detailed evidence. Surprise is therefore expressed when the reality turns out to be somewhat different from the expected pattern (1994, 213).

Why did Germans and others in the immediate postwar period not recognize what is now taken axiomatically as the most significant quality of the Nazi system—the extermination of the Jews? This begs the question, as Kushner points out, of how this belief became axiomatic. To inquire into that process is in no way to imply that the conclusion is incorrect, though assuming this axiom does block off other, often legitimate, areas of inquiry. The point is simply to avoid assuming what contemporaries did not, and to understand why they did not.

To show that the current focus on the “Final Solution” as the centerpiece of German history was not always obvious, moreover, is not necessarily to condemn those who failed to see it as such, though there is much to condemn in the self-centered focus that prevented many Germans from acknowledging great crimes and their complicity in them (Moeller 2003). The point is merely that the problems of the German past are indeed both older and broader than “the Holocaust.”

In the first place, the burdensome legacy of the Second World War includes political authoritarianism and military aggression in addition to genocide. While the Holocaust is today the obvious referent when one speaks of “the German past,” the destruction of the European Jews was only one topic among many (and often not a very important one) in discussions of “the German problem” during and after the war. In the German discourse, “causal” explanations of National Socialism have focused substantially on factors such as delayed modernization, problematic geography, legal inadequacies, economic crisis, nihilism, “massification,” secularization, and capitalism more generally, rather than on anti-Semitism (for detailed analyses of these explanations, see Olick 2005 and Ayçoberry 1981). Sometimes speakers have elided the issues; sometimes they have kept them distinct. The reasons for doing so are complex, dictated by changing interests, identities, circumstances, and traditions. One feature of German public memory that is especially striking in retrospect, however, is how obliquely German speakers often approached “Auschwitz” and anti-Semitism.11 As we will see, this is partly because they used other issues to stand in for the Holocaust. But it is also partly because the problems of the Nazi past extend widely beyond industrial genocide and are often understood, more and less legitimately, in other terms.12

In the second place, in many popular as well as scholarly accounts, National Socialism and the Holocaust are seen as the end results of a long development running from Bismarck, if not earlier, along a preset historical track to the gates of Auschwitz.13 This kind of story, of course, risks misunderstanding the contingencies of history, the crucial turning points through which other outcomes were always possible. At very least, however, the questions of the German past are older than National Socialism, going back to the First World War and earlier. There has never been an American, British, or French question in the same way as there has long been a “German question.” “Germany?” Goethe and Schiller asked in Xenien as long ago as 1796 (and as writers on Germany have been quoting ever since). “But where does it lie? I don’t know where to find the country” (1833, 109). The enigma of German historical identity has rarely been easier in the years since then. Whatever special problems memory of the Nazi period has raised, they thus rest on an already problematic foundation of national history and collective identity.14 “The Holocaust” symbolizes much, but not all, from the German past that troubles its present.

As for whether the Holocaust is the “worst” atrocity in human history: This kind of claim makes sense from neither a social-scientific nor a moral standpoint. From the first perspective, all events are unique; they are also “comparable” in the technical sense that we can only understand them by identifying what they do and do not share with other historical moments. And morally, can we really say there are any definitive criteria for measuring the suffering of one person or group against that of another? Mine is always worse than yours. Whether or not one accepts these arguments, however, does not bear on the question of how claims of uniqueness or comparative judgments of nature or degree work in political discourse—which is my central topic here. When, where, and why do claims of uniqueness or relative horror emerge? Who advocates and who resists them? How are the claims discursively organized? On this last point, it is interesting to note that claims about the uniqueness of the Holocaust (which imply noncomparability) often go hand in hand with claims that the Holocaust is the “worst.” Can the Holocaust simultaneously be noncomparable and worse? Under what circumstances do such claims make sense? None of this, of course, is to discount concerns that efforts to deny the “uniqueness” of the Holocaust have often been part of arguments to avoid responsibility for remembering it. Comparison properly serves the task of understanding, but—as we will see—it can also improperly serve the goal of relativization (see Maier 1988).

Placing Germany in Memory

The question about which aspects of the past have been a problem for German politicians, however, leaves a deeper question unexamined: Why would politicians want to talk about the past in the first place? Why do national leaders use the past as a way to legitimate what they do? When, how, and why does historical imagery legitimate identity and policy? When and where are political leaders expected or even required to give an account of the past? Answering these questions is a particularly important prerequisite for understanding what happens when the past is more obviously toxic than useful, when the “normal” rules of commemoration—whatever they may be—do not seem to apply, as has certainly been the case in Germany since 1945. And lately it seems to have become the case in many other places as well (Olick 2007).

Because the problems of the German past are simultaneously contemporary and historical, specific and general, so too must be our approach to them. We know, for instance, that many different social groups—maybe even all social groups—define and legitimate their collective identities and activities by telling stories of various kinds (Hobsbawm and Ranger 1983; Ricoeur 1984; Wolin 1989; Bruner 1990; Carr 1991). But they have done so in different ways at different times and places. Before outlining the tasks and theses of the book, therefore, it is worth spending a few pages developing some historical perspective on,...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Part 1 Introduction

- Part 2 The Reliable Nation

- Part 3 The Moral Nation

- Gallery

- Part 4 The Normal Nation

- Part 5 Conclusions

- Appendix

- References

- Index