- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Providing a thorough and comprehensive introduction to the study of photography, this second edition of Photography: The Key Concepts has been expanded and updated to cover more fully contemporary changes to photography. Photography is a part of everyday life; from news and advertisements, to data collection and surveillance, to the shaping of personal and social identity, we are constantly surrounded by the photographic image. Outlining an overview of photographic genres, David Bate explores how these varied practices can be coded and interpreted using key theoretical models. Building upon the genres included in the first edition – documentary, portraiture, landscape, still life, art and global photography – this second edition includes two new chapters on snapshots and the act of looking. The revised and expanded chapters are supported by over three times as many photographs as in the first edition, examining contemporary practices in more detail and equipping students with the analytical skills they need, both in their academic studies and in their own practical work.An indispensable guide to the field, Photography: The Key Concepts is core reading for all courses that consider the place of photography in society, within photographic practice, visual culture, art, media and cultural studies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Photography by David Bate in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & History of Photography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Photography Theory

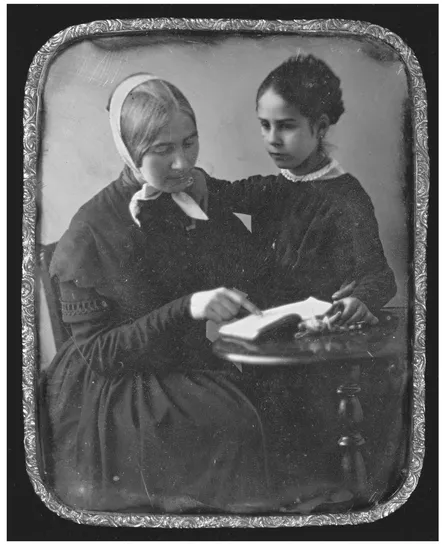

Figure 1.1Woman Reading to a Girl, about 1845, unknown maker. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

The first myth to dispel about “theory” is the idea that we can do without it. There is no untheoretical way to see photography. While some people may think of theory as the work of reading difficult essays by European intellectuals, any practice presupposes a theory. Even someone who claims to be “against theory” is, ironically, actually articulating a theoretical position on theory (albeit one that is far from being new or very useful). Certainly, theory can be difficult, but so is ice-skating to the novice. Like most things, theory becomes easier with practice, just as the new words and concepts that inevitably come with any specialist discipline also become familiar with practice.

Photography would never even have been invented without theories of chemistry, geometry optics, and theories of light. Of course, one does not necessarily need to “learn” all those theories these days since they are now already built into the photographic apparatus itself. However, understanding the consequence of those theories (geometry, light, and optics) on the use of a camera will certainly help to attain control over the medium. Indeed, what is called technique is really a practical theory: the knowledge of how, and what, meanings can be achieved with photographic equipment. Theory then, is not simply a matter of opinion, something purely personal, it is what can be taught: photography theory is the method or means for a systematic understanding of its object. Theory—thinking about things—helps to articulate what it is we are grappling with and to find a way through it. Imagine someone trying to photograph a pet cat. The picture does not seem right for some reason. They turn to an instruction manual for a solution: this is a turn to theory, admittedly a somewhat basic example of theory.

We need new theory when there is a problem to be dealt with and an existing mode of thought that cannot deal with it. The question to be asked here is: what kind of theory does a photographer need? What problems does photography raise? As will be seen below, the main arguments are centered on what photography is (identify its characteristics), how it contributes this to a culture (its use value), and why it has been such a successful invention (social purpose).

A Short History of Photography Theory

We can identify three key periods when outbreaks of theory in and on photography have occurred. The first question inevitably started when photography was invented in the late 1830s. The second was at the beginning of the twentieth century in the 1920s and 1930s, then again in the 1960s and 1970s, which rippled over into 1980s “postmodernism.” The consequences of all these theories remain within contemporary thoughts about photography, but in different ways. Each of these periods had new modes of thinking on photography—which is not to say that interesting thoughts have not emerged at other times, just that the ideas of these periods remain key influences today. If we are still in the shadow of those theories, what better way to evaluate them than to bring them out into the light of day? Let’s briefly consider the three periods and the issues they raised.

Nineteenth-Century Realism

The initial question posed with the invention of what we now call photography, relating to both Daguerreotypes and Talbot’s Calotype, was: how far is photography able to copy things accurately? Can we “trust” photographs as accurate representations of the things they show? The old Greek name for this copying is mimesis, an “imitation” with verisimilitude, which relates to a much larger philosophical discussion (ontology) of how we represent or perceive the world—that which the Victorians preferred to call Nature. The title of Talbot’s first photo book of photographs summed up this attitude towards copying: The Pencil of Nature.

The second question to emerge in this early period relates to this initial issue, in that, if photography copies things, how can it be art? (This in turn begs the question of whether art is anything to do with copying.) It was not long before the advocates of photography as art began to form an aesthetic that would promote photography to the status of art. However, these advocates disagreed as to which qualities of the medium made it art: precision or composition, clarity or idealism, Naturalism or Pictorialism. The values of “artistic photography,” combined with the first question, formed what can be called Pictorialist aesthetics, a set of debates that attempted to situate photography within a field of visual art. This field was already dominated by painting, which in turn had responded to the invention of photography with specifically human theories of vision, that is, Impressionism. Of course to consider these questions in the 1840s, when photography was only just spreading across the world, is very different to thinking about them today.

All the same, a modern commonsense view of photography, where access to a camera is overwhelmingly common, arrives nevertheless at similar conclusions to those of the early debates on photography, albeit in a different vocabulary. In the popular view, a camera is a kind of automated vision that records things in front of it but requires a special creative being to bring it into “art.” The longstanding Romantic belief in the special ability of human imagination is required to make a modern technology like photography “creative.” As a society develops science and technology, “techno-science”, the distinction between special qualities of the creative imagination and technology is put under tension and revised. The faculty of human imagination, seen as separate from technology, was challenged when spirit photographs were faked. The challenge came from technology, too, when the camera appeared to make an image the photographer had not intended. It was not until the 1930s that such propositions were really interrogated— that is, on the full impact of photographic technology on all the arts and culture—when photography began to change the entire notion of creative imagination. (Surrealism remains an important example of this when, in the 1920s, “automatic writing” was advanced in opposition to the established notion of the “creative poet” who agonized literary images out of their angstridden attic existence.

Early Twentieth Century—Mass Media

The emergence of mass democracy and mass media reproduction of photographs in the 1920s and 1930s were bound up with one another, when photography and cinema emerged as key modern mass media tools. Artists proclaimed photography and cinema to be the new technology of the twentieth century, a technology for the masses. Avant-garde and modern theories of photography exploded during this period, and tried, in different ways, to situate the place of photography in the new century. After the First World War had accelerated the technological development of photography, almost anything seemed possible in the new, changed political landscape and many of the ideas generated in this period continue to have an impact on thinking about photography today, and are worth revisiting through concepts of montage, realism, formalism, democratic vision, modernism, documentary, political photography, psychical realism, and others—all formed in this period in avant-garde manifestos (by constructivists, futurists, surrealists, etc.) and by individual writers and photographers.

It would be impossible to summarize all of them, but one of the key essays from that explosion of theory to endure today is “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1936), by the German writer and critic Walter Benjamin. Although Benjamin wrote several essays on photography, all fascinating, his “Work of Art …” essay puts its finger on precisely the real significance of photography in its impact on art and culture. In a famous passage, Benjamin writes:

Earlier much futile thought had been devoted to the question of whether photography is an art. The primary question—whether the very invention of photography had not transformed the entire nature of art—was not raised.1

Benjamin overturns the nineteenth-century debate in one sentence. His essay is packed with discussions and arguments that explore the way that the photographic production and mass reproduction of images have transformed relations to social rituals, art objects, people and the spectator. It is a veritable goldmine of thought. His arguments would go on to inform many subsequent arguments, including the massively popular TV shows by John Berger, and the book, Ways of Seeing, first published in 1972.2 Berger developed the argument that photography had not only transformed ways of seeing high-art painting, which had lost authority with the rise of the new mass media advertising images (also exploited by them for their “high cultural values’), but also demonstrated how all these images helped to structure the way we see each other as men and women. The virtue of Berger’s book is that it paid attention to the pictures themselves, how they “work,” and linked this to a critical analysis of the social purposes for which those images were intended. Ways of Seeing located photography—as it still is today—as part of our private and public social environment, and showed the massive cultural significance and importance photographic images have for the dissemination of social values. This emphasis on meaning and social context provided a platform and introduction for the more sophisticated analytical work on these uses of photography developing in France through the new found interest in semiotics: the study of social signs.

1970s—The Critical Turn

There is no doubt that the rise and consolidation of the communications media industries, including advertising, television, fashion, marketing, and cinema, all became major agents of culture in industrial societies. The role of photographic images in these cultures provoked a range of studies on their significance. In a book called Photographers at Work, the American sociologist Barbara Rosenblum tracked working photographers in advertising, news photography, and fine art to find out how their particular roles determined the look or style of their photographs within each institution.3 In 1965 the French sociologist, Pierre Bourdieu, examined the role of photography among the middle classes as a leisure activity, which, despite the scorn thrown upon it” showed a distinct ambition, no less than the activities of a professional. Roland Barthes, one of the most sustained influential writers on photography today, had already published, in 1961 and 1964, in the French journal Communications, two theoretical essays on photography: “The Photographic Message,” on news photography, and “Rhetoric of the Image,” on advertising.4 The intellectual and cultural excitement of new critical thinking about society and culture in Paris, named as Structuralism by its opponents, also broke out onto the streets with the student revolt of “May 1968.” In the U.S.A., Civil Rights movements raised the issue of race, while the Women’s Movement internationally challenged the existing sexism in cultural attitudes and social positions allotted to women.

The outbreak of theory, including the theory of photography, coincided with these new movements, in their sense of critical social purpose. In this same context, conceptual artists began to use photography too, as a means to challenge the orthodoxies of fine art. Unlike fine art photography, where the craft-value of the image production was itself part of the meaning-value, the use of photography by conceptual artists documented actions, installation work, performances and events, or was part of an artwork. In essence, these artists began to use and interrogate the way photography had overturned traditional notions of art in the manner that Walter Benjamin had indicated in his 1936 “Work of Art” essay. Probably most significant in the UK was Victor Burgin, the English conceptual artist who turned to photography as a basis for his own practice and began to draw together the different tendencies: the critical stance adopted in the semiotic theory of Roland Barthes (and others) and the conceptual framework of art and photography theory. His edited volume of essays, Thinking Photography (1982), drew together some of the key new theoretical arguments about photography during this period.5 By the end of the 1980s, photography finally began to be absorbed into art institutions, gradually developing into the way that it is currently seen—as a dominant form in contemporary art. Photography now forms a vital component of the institutional discourse of art (see Chapter 7: Art Photography). However, photography theory of this period remains a key reference, so it is worth mapping out a more detailed introduction to what it contributes to critical thinking on photography.

The Politics of Representation

Do people ever really think about whether photography is important in their lives? While there are millions of cameras in the world it is hard to imagine people grouped on a street having a heated discussion about an advertising billboard or a newspaper photograph as part of everyday life. Most of us experience photographic images “in passing,” a fleeting glance and an occasional stare as we go about our business, walking down a street, flipping across images on a screen, looking at a magazine page, and so on. Art galleries and photography books are perhaps one notable exception where concentration on specific pictures is more common. So, although photographs surround us in our daily lives in so many spheres of cultural activity, we are rarely very conscious of them. What role does this environment of photographic images play in social relations, in how we see the world, other people in general, or even ourselves? Is it precisely because of their prolific dissemination that we do not really notice the photographs around us? What effects do they have? Do we even see them as photographs?

In my fridge, a milk carton has a photographic image of cows on it. Shown in a green field on a sunny day, the cows look “fresh” and “happy,” so I think of them as “healthy.” Such photographic images are hardly artistic statements (for a start they are in my fridge, not a gallery), but they are significant in how I see the product. Although the cows pictured on the carton are probably not the ones who produced the milk in the carton, I tend to imagine that ones like them did, even though this may be wrong. When you start to look for them, idealized photographs are everywhere, used to incite the desire and appetite of the consumer, and not only in the domain of food.

Fashion, travel brochures, cosmetics, music, phones, computers, jewellry, handbags, automobiles, gardens, animals, people—in fact, almost everything—can be made to look attractive photographically. Governments explicitly acknowledge how powerful photographic images can be in their control of advertising images. The role that photographs play in our everyday life has an importance, such that what we are allowed to see and not see is a matter of political judgment or bound by legal institutions. Although many of us probably see dozens of photographic images almost every day, it is easy to forget their impact upon us.

Critical analysis of such images can help reveal something about how we see ourselve...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1 Photography Theory

- 2 Snapshots and Institutions

- 3 Documentary and Storytelling

- 4 Seeing Portraits

- 5 The Composition of Landscapes

- 6 The Object of Still-Life

- 7 Photography and Art

- 8 Global Photography

- 9 The Scopic Drive

- 10 History and Photography

- Questions for Essays and Class Discussion

- Annotated Guide for Further Reading

- Notes

- Select Bibliography

- Index