![]()

STRENGTH 1: PREPARATION

The preparative phase is the first fundamental phase of negotiation.

On one hand, difficulties can be excluded from the beginning by anticipating counterarguments and collecting legitimisation information.

On the other hand, attaining objectives can be secured by clarifying one’s own interests.

Preparation is comprised of distinct components such as situational analysis, setting one’s targets and arranging convincing arguments. For the Negotiation Master, reviewing essential issues is part of the game, just like a car driver checking the fuel.

Naturally, the extent of preparation depends on the respective situation and the importance of the negotiation.

Former U.S. president Richard Nixon starts his “10 commandments for leadership and negotiation” with this rule: “Always be prepared to negotiate but never negotiate without being prepared.“2

He is described as a negotiator who invested an immense amount of time and energy in preparation. Before meeting Khrushchev for the first time, Nixon spent six months over confidential CIA and State Department material, held phone conferences with political heavyweights like Konrad Adenauer and collected information from ambassadors, experts on Russia and universities.3

This enabled him to counter attacks in an exceptionally professional manner. In one of the negotiations, Khrushchev denounced a U.S. proposition with the words: “This resolution stinks! It stinks like fresh horse shit and nothing smells worse than that!” Nixon recalled from his record that Khrushchev had worked as a swineherd and replied, “I am afraid that the Chairman is mistaken. There is something that smells worse than horse shit, and that is pig shit.” Khrushchev stopped for a moment and laughed.4

However, the preparation phase need not last for months. It can be limited to peering into one’s statement of account and noting the maximum amount available. The whole matter might only last two minutes.

The negotiation process can turn into a beautiful, creative and stimulating game if one’s own interests are clear, options are thoughtfully considered and developed beforehand, and the partner assessed accurately. The unprepared, however, are easily stressed, overworked, cannot grasp why something is offered or withheld and proceed nervously.

Main steps in the preparation

Lack of time is a business reality, also in preparation. Hardly anybody will be able to focus extensively on all areas mentioned. Hence, I will outline the relationship of the areas to each other so you can decide for your negotiation which part you need to stress.

Effective preparation ideally includes the following steps:

- Target definition (strength 5)

- Situation analysis and determination of str

- Negotiation partner profile (strength 3)

- Legitimisation (strength 6)

- The best alternative (BATNA)5

It is evident that the strengths of the Master Negotiator play a big role in the preparation phase. Therefore the chapters of this book correspond to them.

Given all the preparation, it is still essential to avoid a rigid structure and remain flexible in the negotiation. Objectives might change. In the course of negotiation, details of the partner profile might have to be corrected or updated.

The options themselve scan change. A partner might offer additional products that are attractive to the company.

Even the best outcome can change if additional suppliers or other partners enter the market.

In essence, preparation should help to better assess the situation. If the perceived expectations do not fit with reality, it becomes necessary to adapt them during the negotiation. This is not always easy because energy is spent in correcting a trusted picture and admitting to one’s errors.

Which areas should you never omit in your preparation? There are two issues I strongly recommend exploring:

Firstly, start by analysing and determining your objectives in a systematic and clear manner. For details, see the chapter on Strength 5: Target Orientation.

Secondly, the situation directly determines your best strategy. In a competitive situation, legitimisation and the best alternative will be the main issues; in relationship situations, the communicative aspect will become the focal point, etc. (Details about these strategies can be found in the chapter on Strength 2: Strategy).

Next let’s consider two areas that will not be dealt with as strengths: situation analysis as the strategic initial step and the best negotiation alternative.

The situation analysis

Situation analysis occupies the central area of preparation and goes hand in hand with target setting. From it evolves the selection of a negotiation strategy which sets the stage for all further areas.

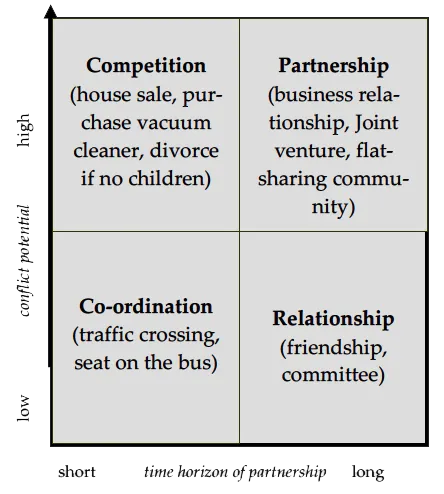

In order to categorize negotiations in a systematic manner it is helpful to distinguish two main criteria.

The first criterion distinguishes short and long term partnerships. There is no difference between a negotiation within the company on who will work during the holidays and a negotiation with a reliable supplier of many years over a price. Both situations demand a strategy geared toward the preservation of a long term partnership.

The determining question is whether the relationship with the partner will continue after the negotiation or whether this is a one-time negotiation situation.

The second criterion aims to assess the value of the conflicting interests, i.e. the consequences of relinquishing one’s interests. In other words: What is at stake? Does this decision threaten my existence? Could I lose my job if we do not receive this order? Or will the result only have peripheral effects? I personally would have preferred to go to Italy, but going to Greece for the family holiday is not the worst option either. Depending on the answer, one can assign a conflict potential to the negotiation.

These two categories can be drawn in a matrix in order to provide a framework to analyse countless negotiation situations:

Any negotiation can be entered into one of the existing four quadrants. Its position facilitates drawing conclusions for a preferable strategy:

Competition negotiations

If the conflict potential is highly elevated, the negotiation can be found in the left upper quadrant. We are dealing with interests which are crucially important in comparison to the relationship itself.

At the same time, the presumable timeline for the relationship is short to medium term. This might also be the case if the decision maker will not have to bear the consequences for his negotiation, e.g. he has to relinquish his leadership function or cannot be re-elected for legal reasons.

In the game theory model, this “player” cannot be “punished” for his behaviour. And how can a person negotiate who does not have to concern himself with the consequences of his behaviour?

Examples of competition negotiation include temporary reorganization managers, nearly the entire top political level, markets with protagonists in fast-changing positions (Russia, CEE), the real estate market as well as the market for equity. A typical (and lyrically adorned)negotiation is the competition for a potential partner or that of rivals in battle. Therefore it is a small wonder that, as the adage goes, both competitions proceed “by any means necessary”.

The reasoning is that retaliation after the negotiation can be neglected. Viewed in this light, one can better understand why the allocation of assets in divorce settlements often goes haywire. Despite the emotions involved, the interests are best satisfied by a competition negotiation. Apart from a potential friendly relationship, there is hardly any benefit in reaching a compromise. The situation changes immediately if common future interests, like children, enter the picture. On the time horizon, the negotiation then moves to the right side of our matrix.

For the same reasons, competitive strategies prevail when dismantling a common enterprise.

In reality, there far fewer text book competition negotiations than the media would have us believe. Even given successive job fluctuations, it is not rare to meet negotiation partners again in a lifetime. This background transforms many negotiation situations to potentially recurring ones and thereby changes the nature of the relationship to long term.

Partnership negotiations

Negotiations in the right upper quadrant are also provided with medium to high conflict potential, but with a long term focus.

In these cases, respect of one another’s needs exceeds the specific negotiation situation. Short term benefit at the expense of the negotiation partner can cause significant disadvantages in the long run. Once trust has been broken it is quite difficult to rebuild. Would you buy another car from a used car dealer who intentionally concealed important details from you the first time?

Partnership situations are often found in supplier or client relationships, for example in supplier contracts for electricity deliveries, spare parts or feeder services.

Generally, all long term service contracts and massive parts of the financial industry (banks, investment brokers) belong to this category. But we also deal with partnership negotiations in flat shar...