![]()

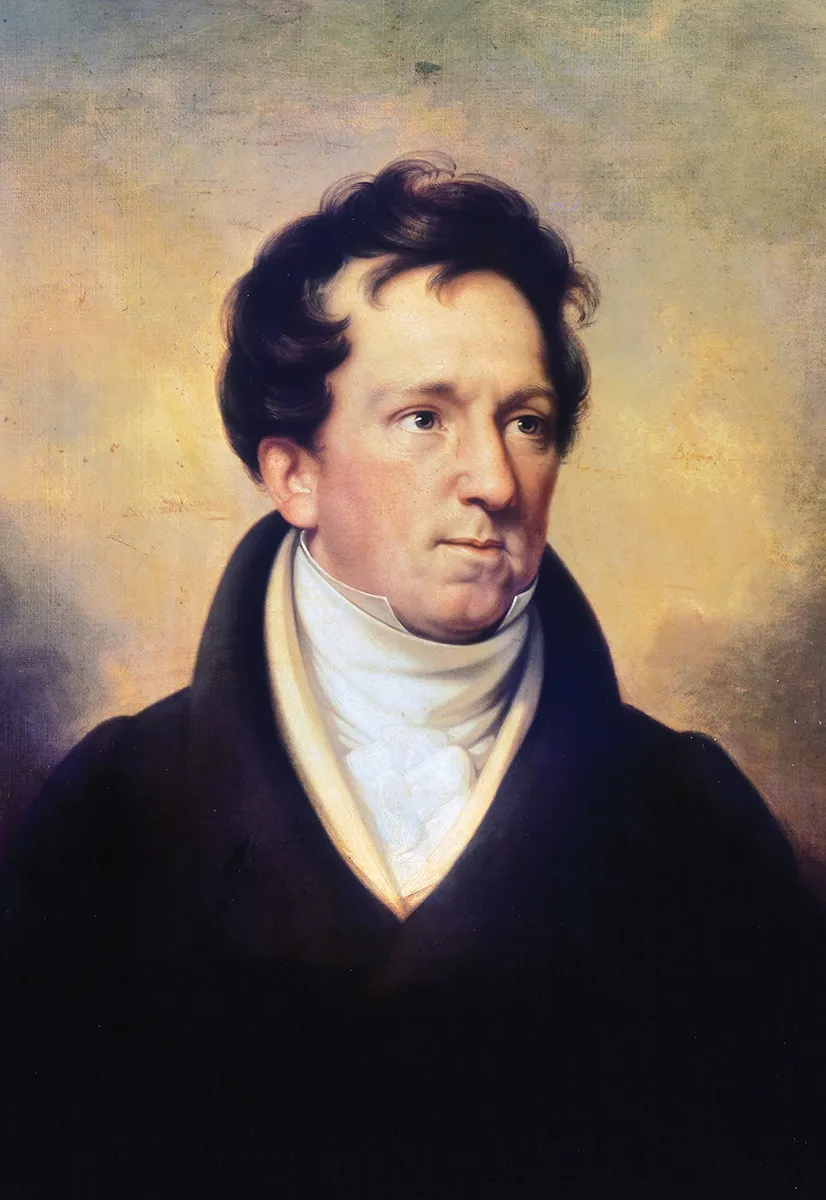

1.1

Nineteenth-century portrait of Porfirio Díaz, Mexican president, in his military uniform.

1

Menswear Through the Ages

This chapter offers an edited introduction to some of the social and historical contexts that have impacted and defined menswear through the ages. The chapter includes a brief chronology of menswear from the ancient world to the twentieth century and is intended to illustrate some of the more significant developments and advancements associated with menswear design. It is hoped that the reader will gain an appreciation of the rich and diverse social history associated with men’s clothing as a precursor to considering contemporary menswear design.

It is only the modern that ever becomes old-fashioned.

Oscar Wilde

![]()

Introduction to Social and Historical Contexts

Menswear through the ages reveals a rich history of clothing and adornment that is largely characterized by a man’s status and function. In this way men’s clothing became closely associated with the contrasting functions of display and utility. The early evolution of menswear was largely concerned with signifying a man’s position and role within a society. This gave rise to opposing standards of dress that were often regulated by sumptuary laws, and where the notion of what might be considered fashionable was determined by class and wealth rather than personal choice. The rise of a European mercantile class during the Renaissance would start to erode the rigid dictates of earlier years; however, the constraints of personal wealth and the imperative to define a man’s role in society continued to influence access to textile materials and dress styles.

One of the more interesting aspects that arose out of the utilitarian and militaristic histories of menswear is the development of classic styles and functional detailing. Both continue to characterize many aspects of menswear clothing today. Classic garments such as a man’s duffel coat or trench coat were developed from practical necessity rather than in response to an aesthetic whim. Such considerations directly contributed to the creation of what we might refer to as design classics with their enduring appeal, while some styles also crossed over into womenswear. Menswear’s other close association is to its style icons, past and present. Originally what was deemed “fashionable” was defined by a monarch or the aristocracy; later, however, under the sartorial leadership of Beau Brummell in the nineteenth century, men’s fashion became codified according to personal style and taste.

1.2

This portrait of King Henry VIII emphasizes the broad, layered silhouette and decorative slashes of the male dress of the northern Renaissance.

Sumptuary laws

One of the more interesting aspects of menswear through the ages is the pervasive influence and impact of sumptuary laws. Essentially, these laws prescribed and reinforced social hierarchies and perceived morals through restrictions on clothing, decoration, and luxury expenditure. The introduction of sumptuary laws in the Middle Ages, and their relatively widespread use until the seventeenth century, became a means of maintaining and reinforcing class distinctions and wealth.

Dress regulation was a feature of life during Roman times, perhaps most notably the restricted use of Tyrian (royal) purple. This effectively rendered purpledyed textiles as status symbols, with use restricted to and reserved for high-ranking Romans and the emperor himself. These laws persisted throughout the Byzantine Empire, when the state controlled the price and quantity of imported goods and regulated domestic manufacturing through the establishment of guilds. With the introduction of silk weaving in Europe around AD 550, silk production became a state-owned monopoly and its use limited to garments and lavish embroideries for the wealthiest citizens, as well as courtiers and high priests.

Sumptuary laws remained a consistent feature of Tudor England under King Henry VIII, who set the dress standard for his royal court. He had an imposing presence, and aspired to compete with the two main European powers of the day, France and the Holy Roman Empire. This famously culminated in the so-called “Field of the Cloth of Gold” meeting between Henry and Francis I of France in 1520, which amounted to little more than an ostentatious display of wealth. Later, in 1574, Queen Elizabeth I of England introduced a series of sumptuary laws, which included for men the banning of “any silk of the colour of purple, cloth of gold tissued, nor fur of sables, but only the King, Queen, King’s mother, children, brethren, and sisters, uncles and aunts; and except dukes, marquises, and earls, who may wear the same in doublets, jerkins, linings of cloaks, gowns, and hose; and those of the Garter, purple in mantles only.” The rules of dressing remained a priority for the royal courts of Europe and were upheld through the system of guilds.

Fashion is the mirror of history. It reflects political, social and economic changes.

Louis XIV of France

Courtly dressing

Although courtly dressing can be traced back to the civilizations of the ancient world, most notably the dynastic kingdoms of the Ancient Egyptian pharaohs, it was not until the Middle Ages that the word “fashion” could be used to describe this collective style. During these times, the fashionable style of dress in Europe was set by the royal courts, each with a monarch and a hierarchy of nobility in attendance. Increasingly, being “fashionable” meant dressing and behaving in ways that expressed one’s social class and dignity.

In the male-dominated societies of the Middle Ages, men’s fashionable dress was characterized by the use of lavish fabrics, vivid colors, and ostentatious detailing. European textile workers became more skilled in producing refined silks and brocades that had previously been imported from the East. This period also witnessed the development of more form-fitting men’s clothes that were cut to fit around the body and emphasize the male torso.

During the fifteenth century, men’s dress styles in northern Europe were greatly influenced by the most lavish and fashionable court of the period, Burgundy. Even the demise of Burgundian power in 1477 influenced male dress when Swiss soldiers and German mercenaries on the battlefield were amazed by the lavish textiles and set about cutting them up and inserting them through their own clothes by pulling them through slashed openings. This gave rise to a court fashion that was prevalent during the reign of King Henry VIII of England.

The structures and protocols of opulent court dressing remained a feature of male dress during subsequent centuries. The sixteenth century marked the rise of Spanish court styles and the introduction of “severe black” for men, which was offset by a striking white neck ruff. Later, as France became Europe’s pre-eminent power, the lavish court dress styles of King Louis XIV were widely exported across Europe to other courts.

The French Revolution of the late eighteenth century interrupted this established system of the court defining fashionable men’s dress: the clothing and textile guilds were abolished and France’s sumptuary laws were repealed. Napoleon Bonaparte later revived a classically inspired court system, but by this time European courts competed for influence and courtly male dress became more ceremonial, inspired by military associations.

1.3

Nineteenth-century portrait of a gentleman, by George Clint. Notice the elaborate and distinctive necktie that was typical of the period.

Mercantile dress

Mercantile dress, an established mode of dress worn by the merch...