- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Few Americans, black or white, recognize the degree to which early African American history is a maritime history. W. Jeffrey Bolster shatters the myth that black seafaring in the age of sail was limited to the Middle Passage. Seafaring was one of the most significant occupations among both enslaved and free black men between 1740 and 1865. Tens of thousands of black seamen sailed on lofty clippers and modest coasters. They sailed in whalers, warships, and privateers. Some were slaves, forced to work at sea, but by 1800 most were free men, seeking liberty and economic opportunity aboard ship.Bolster brings an intimate understanding of the sea to this extraordinary chapter in the formation of black America. Because of their unusual mobility, sailors were the eyes and ears to worlds beyond the limited horizon of black communities ashore. Sometimes helping to smuggle slaves to freedom, they were more often a unique conduit for news and information of concern to blacks.But for all its opportunities, life at sea was difficult. Blacks actively contributed to the Atlantic maritime culture shared by all seamen, but were often outsiders within it. Capturing that tension, Black Jacks examines not only how common experiences drew black and white sailors together—even as deeply internalized prejudices drove them apart—but also how the meaning of race aboard ship changed with time. Bolster traces the story to the end of the Civil War, when emancipated blacks began to be systematically excluded from maritime work. Rescuing African American seamen from obscurity, this stirring account reveals the critical role sailors played in helping forge new identities for black people in America.An epic tale of the rise and fall of black seafaring, Black Jacks is African Americans' freedom story presented from a fresh perspective.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Black Jacks by W. Jeffrey Bolster in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

Harvard University PressYear

1998Print ISBN

9780674076273, 9780674076242eBook ISBN

9780674252561

1. THE EMERGENCE OF BLACK SAILORS IN PLANTATION AMERICA

I am not a ward of America; I am one of the first Americans to arrive on these shores.

JAMES BALDWIN,

The Fire Next Time (1963)

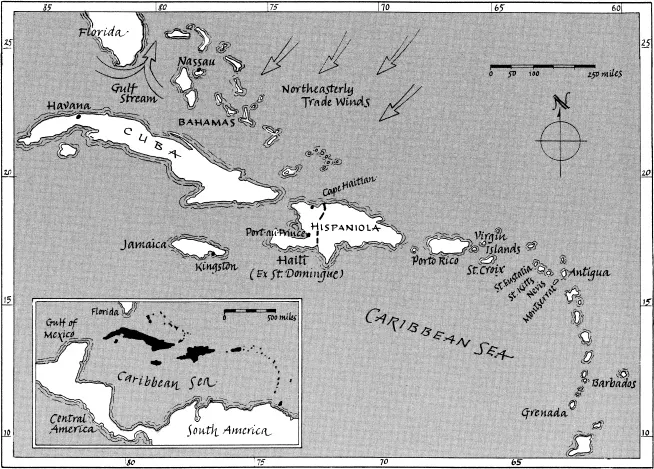

ON A DECEMBER DAY IN 1747 Briton Hammon, a slave to Major John Winslow of Marshfield, Massachusetts, walked out of town with, as he put it, “an Intention to go a voyage to sea.” Tucked into the sandy bight of Cape Cod Bay, some thirty miles south of Boston, and reeking of tidal flats and Stockholm tar, Marshfield was a minor star in the galaxy of Britain’s commercial empire, and only a short walk from Plymouth, where Hammon shipped himself the next day “on board of a Sloop, Capt. John Howland, Master, bound to Jamaica and the Bay” of Campeche for logwood. Experienced at shipboard work, as were approximately 25 percent of the male slaves in coastal Massachusetts during the 1740s, Hammon had not run away. But like all black people in early America who wrought freedom where they could, nurtured it warily, and understood it as partial and ambiguous at best, Hammon seized the moment. Prompted by memories of luxuriant Jamaican alternatives to sleety nor’easters, he negotiated the right for a voyage when his master Winslow’s frozen fields were untillable, and earned a brief sojourn in the black tropics—the productive heartland of the Anglo-American plantation system. Winslow, of course, pocketed most of the wages.1

Hammon’s Narrative of the Uncommon Sufferings, and Surprising Deliverance of Briton Hammon, a Negro Man, the first voyage account published by a black American, indicates the extent to which enslaved sailors and nominally free men of African descent rode economic and military currents to every corner of the eighteenth-century Atlantic world. Hammon’s voyage launched him on a twelve-year odyssey embracing shipwreck, Indian captivity in Florida, imprisonment and enslavement in Cuba (where he toted the Catholic bishop’s canopied sedan chair and “endeavour’d three times to make my escape”), Royal Navy service under fire against the French during the Seven Years War, hospitalization in Greenwich, dockwork in London, and a near voyage to Africa as cook aboard a slaver. Hammon, his black shipmates, and those with whom they conversed were citizens of the world.

Men of African descent had sailed the Atlantic from the time Europeans began their piratical forays and plantation settlements, mustering in the ranks of Columbus, Balboa, and Cortez at the birth of the Atlantic system. Other Africans, including mariners, had traveled to Europe even earlier, both as slaves and as free men. A Venetian oil painting of black waterfront workers in 1495 suggests that no fifteenth-century Mediterranean seaman would have been startled by Africans on the quayside. By 1624, the year British planters settled Barbados, a black seafaring tradition had taken root within the embryonic Anglo-American world. “John Phillip, a negro Christened in England 12 yeers since,” told the Council of Virginia in 1624 “that beinge in a ship with Sir Henry Maneringe, they tooke A spanish shipp aboute Cape Sct Mary.” In 1625 a “negro caled by the name of brase” helped Captain Jones work his ship from the West Indies to Virginia. The historian Ira Berlin has labeled men like Phillip and Brase “Atlantic creoles”—people of African descent who originated neither in the heart of Africa nor in colonial America, but in the expanding commercial world linking the two, black men who often arrived in America not in chains, but as sailors or linguists on commercial ships. “Atlantic creoles” were as accustomed to the foredeck as to the field. They faced fewer liabilities because of color than would their black descendants in the New World slave societies that developed later, and in which race became even more cramping.2

During the middle of the seventeenth century, western European governments stepped up state-sponsored support of private enterprise, creating a highly profitable Atlantic plantation system built on “European capital, American land, African slave labor,” and maritime transportation. Unwilling plantation laborers in Virginia, Barbados, and elsewhere produced commodities such as sugar, tobacco, coffee, and rum for which the wealthy, and later the workers, of Europe developed insatiable cravings. Plantations and ships were peas in the pod of commercial capitalism, separate yet dependent on each other. No other part of the global economy relied as heavily as New World plantations on maritime transportation to import supplies, people, and food, and to export the crop. Colonial plantations transformed the palates of European consumers, redefining as staples the sweetness and smoke that once had been luxuries. Plantations were also central to the “Commercial Revolution” that eroded England’s customary agricultural economy, and set into motion wrenching new forms of labor organization on both sides of the Atlantic—dominated by slavery on an unprecedented scale.3

European statesmen then assumed that the natural order of things was a world in which nation-states competed for what Sir Josiah Child called “profit and power,” not only with force of arms, but through overseas production and trade. As feudalism gave way to capitalism in Europe, privatization of various means of production, notably land, allowed entrepreneurs to accumulate capital. That spurred commercial growth. Legal justifications for the appropriation of producers’ surpluses conditioned merchants to think less of that capital’s human cost than of its investment potential, often in the plantations in which slaves, sailors, and slave-sailors played such important roles.4

The sanction of profit, the severance of mutual obligations between employer and employee, the international influence of racial thought, and the availability of slaves in African markets all seemed to condone the immoral practice whereby certain white individuals in England (along with those in the colonizing states of France, Holland, Portugal, Denmark, and Spain) could attain property rights to other individuals—specifically blacks who worked in plantation colonies. This presence of slavery within capitalism, explains Sidney Mintz, “gave to the New World situation its special, unusual, and ruthless character.” Saluted by coldly admiring eighteenth-century Englishmen as “the mainspring of the machine which sets every wheel in motion,” the trans-Atlantic slave trade peaked from about 1760 to 1780, when a torrent of approximately 65,500 Africans arrived annually in the Americas, a fraction of the approximately 10,000,000 who arrived in chains. The nefarious traffic did not cease until the final smuggler made landfall during the late nineteenth century, long after African Americans had forged themselves into a new people.5

Heroic in proportion and tragic in its human particulars, the Commercial Revolution’s plantation system was a pan-Atlantic phenomenon. Ships and sailors not only followed the setting sun in a linear track from the Old World to the New, bringing capitalism and captive Africans to the Americas, but continuously cross-pollinated an emerging Atlantic world of new ecological, social, and racial relationships. Black sailors emerged from the confluence of forced black labor and maritime transportation that defined the plantation system. As conduits between the new centers of black population on the western rim of the ocean, sailors helped define and connect a new black Atlantic world.

Seamen recognized a daunting kinship between vessels and plantations. Both manifested harshly exploitative elements of feudalism and capitalism, combining in one workplace the virtually unchecked personal authority of the feudal lord and the impersonal appropriation of workers’ labor so fundamental to capitalism. One captain, white sailors complained in 1726, treated them as if they were “bought Servants”; another “refused to Supply them with a Necessary quantity of Provisions,” reducing them “to the Utmost Extreamity.” Beatings to enforce discipline aboard the sloop William in 1729 “did Occassion Great Effusion of Blood.” Yet seafaring nevertheless appeared desirable to black males whose alternative in the European-dominated Atlantic world remained debilitating field labor with heavy hoes or billhooks and the substantially more savage discipline of laws designed to regulate slaves. Freedom beckoned—inconsistent and illusory though it became aboard the tempestuous ships of an expanding commercial economy.6

By the late seventeenth century, enslaved seamen worked in even predominantly white provinces like Massachusetts. In Boston in 1690, “a Negro man, Sambo by name (being young, strong, & able & of very good health),” was shipped by his owners on board a ketch bound for Barbados at “thirty shillings by the month certain, & more if any higher wages were given to any foremastman that should after be shipped.” Clearly Sambo could dexterously “hand, reef, and steer,” the essence of the seaman’s craft. Skill, moreover, allowed a black sailor to hold his own among fellow tars, even while facing peremptory challenges. Strolling upon Boston’s Fort Hill in 1694, a self-confident black man who belonged “to the Sorlings Frigat” struck up a conversation with two white youths, and offered to buy one’s earring for a piece of eight. With “two pieces of eight and a piece of gold abt the bigness of an English Crown” that he said he “got . . . privateering,” the sailor ashore with “ready money” epitomized seafaring liberality and affronted whites’ image of black subservience. “Sirrah come along with me,” crowed a white man in pursuit, before subjecting the privateersman to the indignity of a search.7

Nevertheless, paternalistic New England masters allowed maritime slaves certain leeway. Although John Mico carefully instructed the captain to whom he hired his slave Jeffrey for a voyage to Barbados and London in 1703 to “restrain and keep him . . . as if he were your owne,” he also explained that Jeffrey “may have a mind to see my father and Brother [in London], if he should hint so much to You, let Ye Black Gentleman have his Desire.” Despite white constraints, the small community of seventeenth- and early-eighteenth-century black seafaring men found a degree of personal freedom in the regimented milieu of the ship alien to most plantation slaves, and a cosmopolitanism denied even to many urban blacks. If any slaves still wore the mantle of quasi-autonomy once characteristic of “Atlantic creoles,” it was sailors.8

Resentful slaves ashore hungered for that mite of liberty. Pompey, a slave who fled his New England master in 1724, successfully hid in the firewood aboard Captain Moffatt’s Morehampton. Although Moffatt swore that “sd Negro was altogether useless aboard ship,” Pompey sailed to Oporto, Portugal, where he again outfoxed the exasperated Moffatt “and secretly conveyed himself to Spain,” before coming home to New England with Captain Gilley. The choice to return may well have been his own. Moreover, with two trans-Atlantic passages under his belt, Pompey had acquired skills useful for future voyages— authorized or not.9

One higher-stakes alternative to such limited freedom-seeking within the commercial system then existed. Bold black seamen joined disgruntled white soldiers, sailors, and servants confederating as pirates along sun-drenched Caribbean sea-lanes. Contemptuous of the authority that had always repressed them, truculent as game cocks, and unencumbered by attachments except to like-minded comrades, these “desperate Rogues” created an egalitarian, if ephemeral, social order that rejected imperial society’s hierarchy and forced labor. Buccaneering tempted black seamen with visions of invincibility, with dreams of easy money and the idleness such freedom promised, and with the promise of a life unfettered by the racial and social ideology central to the plantation system. Unattached black men operating in the virtually all-male world of the “Brotherhood of the Coast” realized those yearnings to a degree, but also found abuse and exploitation, as well as mortal combat and pursuit.10

By 1716 the Bahama Islands were referred to, with cause, as a “nest of Pirates.” New Providence became their headquarters, much to the dismay of local planters, who lamented that the pirates passed time “plundering the Inhabitants, burning their Houses, and Ravishing their Wives.” The few slaves on New Providence capitalized on this destabilization, becoming “very impudent and insulting.” Some fled to the buccaneers. From 1716 to 1726, the heyday of large-scale European-directed piracy, some five thousand buccaneers sailed “under the banner of King Death.” From a theater of operations rooted in uninhabited Caribbean harbors, the sea robbers “dispers’t into severall parts of the World.” Most were white, and most turned pirate when other pirates captured the merchant ships on which they sailed. No accurate numbers of black buccaneers exist, although the impression is that they were more numerous than the proportion of black sailors in commercial or naval service at that time.11

Few blacks in the early-eighteenth-century Atlantic world had any choice but slavery, and little room within slavery for the sheet anchor of family. Partially socialized to the ways of Europeans, more so, at least, than many plantation slaves, black sailors welcomed the opportunity to give up slavery in legitimate commerce for a share of spoils as pirates. When Edward Teach, better known as Blackbeard, fought to his death at Ocracoke Inlet in 1718, five of his eighteen-man crew were men of color. According to the Governor’s Council of Virginia, the five blacks were “equally concerned with the rest of the Crew in the same Acts of Piracy.” One of Teach’s men was remembered as “a resolute Fellow, a Negroe, whom he had bred up” and trusted. A few years earlier, the pirate captain Lewis had recruited a crew in the West Indies ultimately numbering eighty men. “He took out of his Prizes what he had occasion for, 40 able Negroe Sailors, and a white Carpenter,” wrote Daniel Defoe. Some men volunteered; others were forced. Lewis began his depredations with a canoe and six comrades near Havana. They seized a Spanish pettiauger (a modified dugout), and with that captured a turtling sloop, and kept leap-frogging from one vessel to another yet larger until they took “a large pink-built ship bound from Jamaica to the Bay of Campeachy.”12

No first-hand testimony exists to document blacks’ attraction to piracy. But pirate captains like Bellamy spoke straight to the oppressed. “Damn ye, you are a sneaking Puppy,” he is reputed to have snarled at a captured merchant captain in 1717, “and so are all those who will submit to be governed by Laws which rich men have made for their own Security, for the cowardly Whelps have not the Courage otherwise to defend what they get by their Knavery . . . They vilify us, the Scoundrels do, when there is only this Difference, they rob the Poor under the Cover of Law, forsooth, and we plunder the Rich under the protection of our own Courage.” Reinforcing this ideological appeal was pure pragmatism. “In an honest Service,” quipped Captain Bartholomew Roberts, “there is thin Commons, low Wages, and hard Labour; in this, Plenty and Satiety, Pleasure and Ease, Liberty and Power . . . when all the Hazard that is run for it, at worst, is only a sower Look or two at choking. No, a merry Life and a short one, shall be my motto.” Piracy substantially multiplied a black sailor’s immediate freedoms. The promise of “Pleasure and Ease,” even if passing, appealed to bold men degraded by extortion and race.13

Pirates also elected skilled seamen of color to positions of authority. “There is a principal Officer among the Pyrates, called the Quarter-Master, of the Men’s own choosing,” explained Defoe. Acting as a “civil Magistrate,” the quartermaster ensured that necessaries were distributed equally, and that no man—including the captain—got more than his share. In keeping with their high post, quartermasters often led boarding parties or took charge of captured vessels. When Captain William Kidd anchored off Gardners’ Island, New York, in 1699, two sloops spent several days lying near to him, one of whose “Mate was a little black man . . . who, as it was said, had been formerly Captain Kidd’s Quarter Master.” In 1696 a runaway West Indian slave named Abraham Samuel sailed as quartermaster on the pirate ship John and Rebecca during a voyage from the Caribbean to the Indian Ocean. Later, in an odd twist of fate, he became “king” of Fort Dauphin on Madagascar, with slaves, wives, and trading profits at his disposal. In “Honest service” a skilled black sailor had little authority, but among freebooters a man like Abraham Samuel could be popularly elected to a position of honor contingent upon his strength, charisma, and wits.14

Yet most still lacked the stomach “to go upon the Account.” “A Negro man named Francisco” charged with piracy was acquitted by a special Court of Admiralty held in Boston in 1724, “it appearing to Said Court he was taken out of a Vessell on the high seas from one Capt. Lupton & was a f...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction: To Tell the Tale

- 1. The Emergence of Black Sailors in Plantation America

- 2. African Roots of Black Seafaring

- 3. The Way of a Ship

- 4. The Boundaries of Race in Maritime Culture

- 5. Possibilities for Freedom

- 6. Precarious Pillar of the Black Community

- 7. Free Sailors and the Struggle with Slavery

- 8. Toward Jim Crow at Sea

- Tables

- Notes

- Acknowledgments

- Index