![]()

1

Native Borders

SALMON MOVED FLUIDLY BETWEEN THE WORLDS OF ANIMALS and human beings in early Northwest Native ethnographies and oral traditions. Salmon and other animals regularly assumed human shape, their ability to blur the line between species demonstrating the strong connections between humans and nonhumans. Salmon People appear often in the stories passed down from one generation to the next. In one Coast Salish account a man and Raven were out hunting on Vancouver Island. Paddling along in their canoe, they suddenly dropped into a hole and landed on the roof of one of the Salmon People’s homes. Wanting to be good hosts and currently in human form, the Salmon People took their children to a nearby river and immersed them in the water. The human children immediately turned into salmon, which the parents then cooked and generously offered to their visitors. As they ate, man, Raven, and the Salmon People carefully saved the bones and returned them to the river following their meal. The children were “reanimated and again became humans.”1

In Katzie (Halq´eméylem) memory the leader of Sheridan Hill, Swanaset, journeyed to a distant land in search of the Sockeye Salmon People. Once he found them, Swanaset successfully wooed the daughter of the Sockeye Salmon chief, married her, and lived with her family for a time. Each morning, Swanaset watched his mother-in-law return from the beach cradling a sockeye salmon as though it were a child. The family roasted the fish and paid close attention to the bones as they ate. After the meal Swanaset’s mother-in-law took the bones to the beach, gently tossed them into the water, and returned to the house with a young, happy boy. After a while Swanaset’s salmon wife accompanied him back to his home village on the Fraser River. Because her relatives promised to visit every summer, she brought Swanaset’s people the gift of an annual sockeye salmon run.2

Salmon was the skeleton around which Northwest Natives structured their lives. They were children and spouses, they grew in economic significance over time, and they were crucial to the evolution of Indian society. Such intimate connections were not automatic, however. Like any relationship, this one demanded maintenance and care; the region’s Indians worked out precisely what that maintenance and care would look like over thousands of years. They transformed their cultural practices, altered their community structures, and drew lines to limit access to important salmon fishing sites. They did these things to ensure that their relationship with salmon remained strong. They did these things to ensure the salmon kept coming. And for the most part, it worked.

LEARNING TO LIVE OFF THE WATER

Twenty-five thousand years ago the Pacific Northwest was covered with ice, inhospitable to both humans and salmon. When the ice started melting around fourteen thousand years ago, the area gradually transformed into more amenable habitat. As environmental conditions stabilized, the salmon population increased in overall abundance. This new availability, together with Native advancements in processing and storage techniques, likely translated into a greater reliance on salmon for food and greater surpluses for trade. By the time white newcomers arrived on the west coast of North America in the 1770s, Native peoples had developed extremely effective and often complex methods for taking salmon. This co-evolution of environment and culture brought salmon to the center of Indian subsistence practices.

The seven species of anadromous Pacific salmon (Oncorhynchus spp.) that came to live in Salish Sea waters were impressively adaptable and evolved over millions of years. The Salmonidae family may be a hundred million years old, and the genus Oncorhynchus probably emerged between ten to fifteen million years ago.3 This was well before geologic processes created the Cascade and Olympic mountain ranges sometime between four to seven million years ago. Some older salmonids, like the six-foot-long saber-toothed salmon, did not survive the intense changes in habitat caused by tectonic plate movements and lava flows. However, the modern salmon species that emerged between one to two million years ago proved resilient enough to live through the glaciation of the region.4 While the rivers feeding the Salish Sea were frozen, these species found temporary homes to both the north and the south. When the glaciers began melting, massive flooding destroyed habitat suitable for salmon reproduction. Gradually, however, rivers found stable beds, and smaller trees and shrubs gave way to Douglas fir, western hemlock, and the western red cedar. As the trees grew in size, they helped root streams and rivers to their channels and provided shade to cool the water. Trees fell across these waterways and created pools. By three thousand to five thousand years ago, the Northwest Coast presented ideal Pacific salmon habitat.5

Human beings most likely reached the north Pacific Coast much later than the first salmon. People arrived in the region as early as twelve thousand years ago, but they remained nomadic and dependent on a wide variety of resources.6 While human beings exploited salmon and developed fishing technologies early on, sea levels, the climate, and other environmental conditions were volatile enough that flexible subsistence tactics remained important for survival.7 Shell middens—piles of discarded shells, other food remains like bones and antlers, as well as some cultural artifacts—dated between fifty-two hundred and sixty-two hundred years ago suggest that people depended more on near-shore resources and that, on some parts of the coast, food security meant that they tended to move around less than previously. Although these people definitely consumed salmon, they could not yet depend on the fish for their primary food source.8

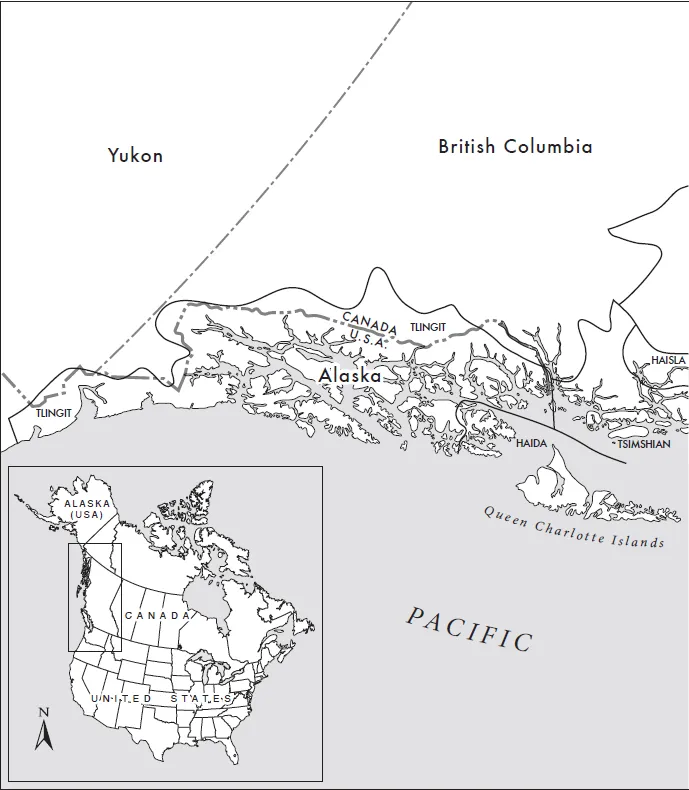

The interwoven environmental and cultural changes that transformed early Northwest inhabitants into skilled fishers took thousands of years. But as of fifteen hundred years ago, many of the region’s indigenous communities were well established and had developed subsistence patterns and group territorial boundaries that aligned with their most prized resources. These peoples composed independent local groups, tribes, and occasionally even confederacies, but they do not appear to have had any lasting political unity prior to the arrival of whites.9 We do not know what these groups called themselves or each other in the pre-contact period, but today it is common to refer to these communities according to their historical language affiliations: the Tlingit, Haida, Nisga’a (formerly Nishga), Tsimshian, Gitxsan (slightly inland), Haisla, Heiltsuk (formerly Bella Bella), Nuxalk (formerly Bella Coola), Oowekyala, Kwakwaka’wakw (formerly Kwakiutl), Nuu-chah-nulth (formerly Nootkans), K’ómoks (formerly Comox), Shíshálh (formerly Sechelt), Pentledge (formerly Pentlatch), Ditidaht (formerly Nitinat), Skwxwú7mesh (formerly Squamish), Halq´eméylem (includes the Stò:lō), Nooksack, Straits Salish, Makah, Quileute, Quinault, Twana, Chemakum, Lushootseed, Chehalis, Lower Columbia Athapaskan, Cowlitz, Cathlamet, and Chinookans. Coast Salish territories extended from today’s southwestern British Columbia into what is now western Washington State, and so wholly embraced the waters of the Salish Sea.10

MAP 1.1 Northwest Coast Native Language Groups. Note how the Straits Salish language group’s territory spans the international border at the forty-ninth parallel. Source: Map redrawn and adapted from Suttles, Native Languages of the Northwest Coast. Map adaptation reproduced here with permission of the Suttles Estate and the Oregon Historical Society.

Although the lush greenery, numerous rivers, and accessible coastlines of the Northwest suggest that people must have had an unlimited abundance of resources before white contact, the reality of food availability was far more uneven and complex.11 Most Native villages along the coast gradually intensified their dependence on salmon and other marine resources, but each group’s immediate environment greatly influenced how they learned to get their food and which foods they depended on most. In fact, local variation in access to resources like salmon could be quite extreme. In Kwakwaka’wakw territory in the northern reaches of today’s Vancouver Island, poor salmon access in some areas was a constant problem, while other groups enjoyed surpluses so immense they could not possibly harvest the entire catch.12 Some groups only periodically suffered scarcity and starvation when a salmon run failed, but other communities had such limited access to productive fishing, hunting, or plant-gathering sites, lean meals were more common. This was particularly true in the far north as the range of food available was less diverse. The availability of resources like salmon, shellfish, and berries thus influenced where groups stopped over or where they settled and so shaped the evolution of subsistence practices and technologies.13

Some of the most basic early fishing methods involved hooks, spears, and harpoons, but even such simple pieces of equipment could result in enormous harvests of salmon. John Jewitt, a Bostonian held captive by the Nuu-chah-nulth at Nootka Sound in the early 1800s, later reported that although his captors were not great hunters, “there are few people more expert in fishing.” His admiration was born of personal experience: though he tried to mimic Nuu-chah-nulth spearsmen several times, Jewitt was never able to spear a fish, admitting that “it require[d] a degree of adroitness that I did not possess.”14 In the early twentieth century the anthropologist Bernhard Stern observed similar abilities among Lummi spearsmen, who handily caught fish after fish by striking the animal’s spinal cord, killing it instantly.15 The combination of such skill, extremely effective fishing techniques, and abundant regional salmon runs ensured a successful catch. “Such is the immense quantity of these fish, and they are taken with such facility,” Jewitt wrote of the Nuu-chah-nulth chief Maquinna’s supply in the early 1800s, “that I have known upwards of twenty-five hundred brought into Maquin[n]a’s house at once, and at one of their great feasts, have seen one hundred or more cooked in one of their largest tubs.”16

As time passed, Pacific slope Indians developed increasingly sophisticated fishing devices. Weirs—fence-like obstructions that forced salmon to halt their course upstream—were complex structures that required significant labor to build. Usually set on smaller rivers or streams, weirs made salmon more accessible to dip nets, spears, and gaff hooks. People built weirs on the southern bank of the Fraser River near what is now the city of Vancouver as early as forty-seven hundred years ago, and remains in southeastern Alaska indicate that weirs were used there approximately three thousand years before the present.17 Fish traps also became increasingly popular along the coast. Traps typically led the fish into an enclosed space from which they could not retreat or escape and so made them easy prey for fishers with nets, spears, or clubs.18 According to early outside observers, traps and weirs were well designed and impressively productive. John Jewitt reported that the Nuu-chah-nulth caught more than seven hundred salmon in fifteen minutes with their “pot.”19 On Simon Fraser’s 1808 trip down the river later named for him, the North West Company’s front man described a clever combination of weir and trap that was “a work of some ingenuity.”20

Fishers also designed effective net-fishing techniques for freshwater and saltwater environments. Many groups used nets to take advantage of both natural and constructed platforms that protruded over the eddies where salmon linger and rest on their upstream journey. Simple, handheld dip nets were particularly efficient in such spots. Towing nets between two canoes allowed fishers to trawl downstream and capture the salmon working their way up against the current.21 Indians to the south—especially the Chinook peoples who lived near the Columbia River—frequently used seine nets as well. Long and narrow, the nets encircled up to one hundred fish in one toss of the net, and fishers often dispatched these nets from river banks in a process known as beach seining.22 Although less commonly used, fishers likewise designed the more intricate and effective gill net, whose precisely measured mesh sizes snagged fish by the gills as they moved through the webbing. When a sizable catch was so entangled, the fishermen pulled them ashore. Because gill nets had to be set in places where salmon were less likely to notice them, their use remained limited until the late nineteenth century.23

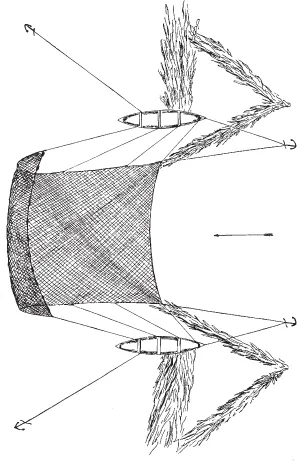

FIGURE 1.1 Diagram of a Straits Salish reef net (c.1888–1889). Drawing by J. W. Collins. Source: Originally published in the United St...