This book is available to read until 23rd December, 2025

- 334 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

About this book

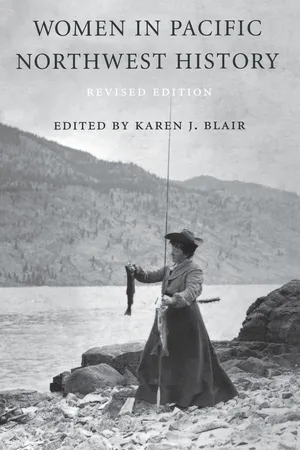

This new edition of Karen Blair's popular anthology originally published in 1989 includes thirteen essays, eight of which are new. Together they suggest the wide spectrum of women's experiences that make up a vital part of Northwest history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Women in Pacific Northwest History by Karen J. Blair in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1

NEW DIRECTIONS FOR RESEARCH

More than ten years ago, I introduced the first edition of this anthology with these words:

When we visualize the history of the Pacific Northwest, we can quickly reconstruct the roles that men played. Early explorers, trappers, missionaries, traders, the Indian chiefs, loggers, sailors, pioneer farmers, miners, businessmen, and aeronautical engineers—all these leap easily to mind. Women are conspicuously absent from the colorful pictures that rise before us. Yet how considerably this omission distorts the truth. The bias that has dismissed women's varied and critical contributions to Washington and Oregon history begs for correction.

The 1988 edition of Women in Pacific Northwest History attempted to rectify the imbalance. Yet in the course of the ’90s, new research emerged to broaden and deepen our knowledge and analysis of women's historical experience in Washington and Oregon. I am delighted to include new essays by Susan Armitage on historiography, Mary Cross on quilts, and Jerry García on Chicanas and to reprint here material by David Peterson del Mar on domestic violence, Maurine Weiner Greenwald on women and unions, Sylvia Van Kirk on Native American wives of fur traders, and my own case study of a Seattle music club. This edition spans a much wider spectrum of history, from late-eighteenth-century traders to the modern Chicana experience.

I am sorry that it is not possible to include many other fine contributions, including the work of Lillian Schlissel on the Mallek family, Lorraine McConaghy on conservative women of the Seattle suburbs in the 1950s, Mildred Andrews on women's places in King County, Washington, Ron Fields on the painter Abby Williams Hill, Mary Dodds Schlick on Columbia River women's basketry, Sandra Haarsager on women's voluntary organizations and on Mayor Bertha Landes, Julie Roy Jeffrey on the missionary Narcissa Whitman, G. Thomas Edwards on the fight for woman suffrage, Dana Frank on union activists, Jacqueline Williams on pioneer cooking, Nancy Woloch on the landmark Supreme Court case Muller v. Oregon (ushering in protective legislation for women), Wayne Carp on adoption, Amy Kesselman on defense workers during World War II, Catherine Parsons Smith and Cynthia Richardson on the composer Mary Carr Moore, Linda Di Biase on the Seattle years of the writer Sui Sin Far, Marilyn Watkins on rural women, and Vicki Halprin on women painters. The scope and strength of recent scholarship makes for a delightful dilemma: rather than offer a comprehensive overview of the literature, I have identified five areas for consideration: New Directions for Research, Politics and Law, Work, Race and Ethnicity, and the Arts.

The following bibliographical essay by Susan Armitage, with dozens of useful suggestions for further study, catalogs the growing sophistication of recent scholarship in the field of Northwest women's history. Scholars are no longer content to embellish traditional histories of the accomplishments of Northwest men with biographies of a few unusual women who mastered skills generally acquired by men, such as the cowgirls, the Roman Catholic missionary and architect Mother Joseph, and the Socialist Anna Louise Strong.

Nor are they willing to flag a few exemplary exponents of “women's work” in such arenas as volunteerism, motherhood, or teaching, the traditional roles for women. Instead, Armitage pushes us to note the viewpoints of new research, especially in the context of women's relationships to others, observing the nuances that gender as well as race and class effect. She reminds us that women are employees of bosses, employers of workers, wives to husbands, mothers to children. They are farmers of the land, missionaries to the Native Americans, trappers for the fur traders, authors to readers, teachers to students, nurses to patients, mayors to constituents, neighbors to neighbors. They manage convents, households, farms, and missions. By surveying new scholarship for women's relationships in six categories, Armitage enables us to embrace the complexity of women's interactions with their world and assess the impact they have made in history.

Happily, even as they are printed, her suggestions grow outdated. New scholarship emerges daily to address topics deserving exploration. Several new studies on neglected subjects will become available in the future to students of Northwest women's history. Among those will be Frances Sneed-Jones's research on African American women's clubs, Susan Starbuck's study of the environmentalist Hazel Wolf, Doris Pieroth's study of mid-twentieth-century women educators, and Gail Dubrow's program to map the spaces utilized by Washington's minority women. We can look forward to a twenty-first century in which women's history continues to enjoy exploration as a vital part of Northwest scholarship.

Tied To Other Lives: Women in Pacific Northwest History

I never set out to deliberately de-mythologize the West, but…when you try to make your characters real and layered and tied to other lives in other places—your work has the inevitable effect of dismantling the myth of the West as the home of heroic, loner white guys moving through an unpeopled and uncomplicated place.

Deirdre McNamer

Some facts are so obvious that we tend to forget them, and one is that the Pacific Northwest could not have been a site of continued human habitation without women. Women are essential in all societies: they assure continuity physically by birthing the next generation and psychologically by raising the children who claim the land and build lasting communities on it.1 Once we understand how basic the presence of women has been to the Pacific Northwest, we can begin to see history through their eyes. As we do that we will find, as the Montana author Dierdre McNamer did, that women's lives are “real and layered and tied to other lives in other places.”2 That realization requires us to think of Pacific Northwest history in new ways. This essay begins with a background sketch showing how women's historians have come to understand the significance of gender relationships. Building on that knowledge, the essay shows the importance of gender relationships in six different areas: the lives of American Indian women, intercultural relations, Euro-American migration and settlement, social reform, labor, and community building. The larger goal of the essay is to demonstrate the way in which the focus on relationships provides a basic conceptual framework for the study of Pacific Northwest history.

As women's history has developed over the past thirty years into a major field within American history, ways of thinking about women in historical terms have changed. At first, in the 1970s, women's historians concentrated on recovering the lives of overlooked women—first the famous ones, and then lesser-known ones—and adding them to the historical record.3 As the historical details of women's lives were recovered, it became obvious that appropriate female behavior (often summed up in the term womanhood) was not an unchanging ideal but a concept that changed from one historical period to the next. Sometimes the changes were abrupt, as in the 1920s when the cigarette-smoking flapper with her short skirts and bobbed hair repudiated her mother's long skirts, long hair, and modest behavior. Sometimes the changes were slower, as in the long struggle for woman suffrage. It took almost a century for women to convince men that females should vote.4 As women's historians were working to put women into history, feminist cultural anthropologists were discovering that there was wide variety in the meanings that different cultures have given to sexual difference.5 Building on this insight, the historian Joan Scott's influential 1986 article, “Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis,” proposed gender as a basic analytic category, as important as other commonly used historical concepts like race and class. Scott observed that the way a particular society defines the difference between the sexes—gender—is the key to understanding other relationships of difference and power within that society.6

Women's historians now believe that gender relationships are what hold a culture together. You might say that it all begins at home. The way a particular culture views the difference between the sexes shapes relationships between husband and wife and between parents and children and establishes a gendered division of labor within the family and in its wider kinship network. The gender relationships that operate at a personal and individual level structure people's expectations about the connections between private and public power and their understanding of how those power relationships operate. For example, in the highly patriarchal world of colonial America, women were defined as inferior and dependent upon men. Women did not expect to play leadership roles in public matters such as politics or formal religious observances. With the exception of a few famous rebels like Anne Hutchinson, colonial women knew that their roles were subordinate and private. But in differently organized groups, such as American Indian societies where the kinship network was paramount, power was often so diffused as to be hard to locate, the difference between public and private was small, and women assumed a wide variety of roles. As these brief examples show, attention to gender relationships offers historians a new and powerful way to understand the power relationships within a given society.

At a more personal level, individuals rarely think to question the family relationships, work roles, and public power structures of their own society, and they are surprised when they discover different gender relationships in other cultural groups. For example, when Phoebe Judson pioneered the Nooksack Valley with her family in the 1880s, she felt a strong “bond of womanhood” with the Lummi woman she knew as “Old Sally,” arising out of their common concerns for their children and family. But for all their commonalities, the two women were, as Phoebe realized, very different. She thought it was because she and her family had progressed to a “higher stage of civilization” than Sally and her fellow Lummis.7 We, however, can see that each woman was embedded in a different gender relationship. They inhabited different networks of power relationships, beginning with marriage and kinship ties and patterns of economic livelihood, widening outward to relationships among different races and access to economic opportunities and political power. Their expectations about how people should interact were based on their own gender relationships, specific to their own societies. Given these unarticulated differences, it is no wonder that cultural misunderstandings and conflicts were so prevalent when white pioneers interacted with American Indian peoples.

By focusing on the gender relationships of different cultural groups, historians can link the life of an individual woman or man to larger generalizations about the public issues with which regional history is concerned. Family and kinship relationships are replicated in the ways communities are organized, and that organization in turn shapes politics at the nonlocal level. Gender thus gives us a way to understand the link between the lives of ordinary people and great national events, such as, for example, the role shifts that occurred during World War II when many young men went off to war and their wives took new and unaccustomed jobs in Pacific Northwest shipyards and airplane factories. Above all, we now have a way to think about how relationships of gender, race, and class interact when peoples of different races and cultures, such as Phoebe and Sally, and Euro-American pioneers and indigenous peoples, met in the Pacific Northwest.

There is much about the history of Pacific Northwest Indian societies before contact with Europeans that we will never know, but gender analysis gives us a place to start. Women's history has taught us that for most women work and kinship have been intimately related. In Pacific Northwest Indian societies, the tribal unit was a kinship network that cooperated to gather, hunt, fish, and grow the food necessary for life. We can easily see how work and kinship interacted in the lives of Indian women. Or we would, if the male anthropologists who did the early studies of Pacific Northwest Indian groups had paid more attention to women's work!

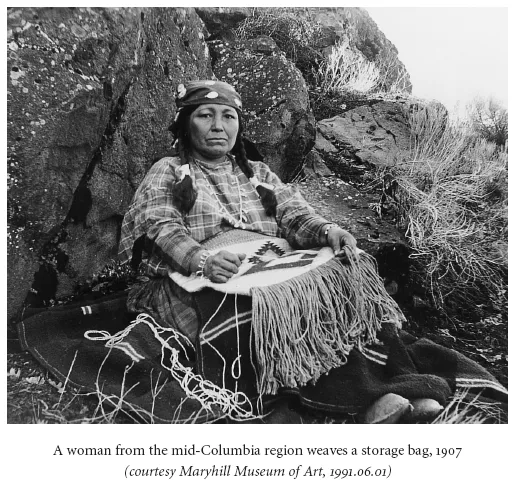

From scanty sources, we can begin to piece together an outline of women's lives before white contact. The Plateau tribes (so called because of their location in the interior Pacific Northwest) followed a seasonal round of gathering, hunting, and fishing activities. Women provided about half the food supply, a finding that is consistent with worldwide reconsideration of the importance of women's activities in so-called hunter-gatherer societies. All tribal work was strictly gender-divided, but there was no indication that men's work was regarded more highly than women's work. Nor in the ceremonial and religious aspects of life did there appear to be much gender difference. It is difficult to fully grasp the worldview that life in such tight-knit, traditional societies produced, but one route is through serious appreciation of Indian art. A book such as Mary Schlick's Columbia River Basketry: Gift of the Ancestors, Gift of the Earth shows us the ways in which all aspects of life—work, religion, and kinship—came together in the baskets that women wove.8 Baskets were practical implements of daily life and work, but the skill with which women wove them, their decoration, and their wider uses had important religious and symbolic meaning to the native peoples of the Columbia River. Another splendid example of the connection between culture and women's arts is offered in A Song to the Creator: Traditional Arts of Native American Women of the Plateau. One of the most important contributions of this book is its recognition of cultural continuity: women's traditional arts are still practiced today.9

The lesson of cultural continuity is also a major theme of Margaret Blackman's life history of Florence Edenshaw Davidson, a Haida woman. This study provides a useful model. Blackman, an anthropologist, interviewed Davidson many times, drawing from her not only recollections of family and tribal history but also a clear sense of the ways that Davidson adapted traditional customs and attitudes to contemporary life. Other anthropologists, working carefully with material gathered early in the century, have begun to tease out a better understanding of women's lives and of their important roles in their societies.10

One unusual regional source is the writings of Christine Quintasket (Mourning Dove) of the Colville Confederated Tribes of eastern Washington. Generally acknowledged as the first female American Indian novelist, Mourning Dove had a life better documented than mos...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Part 1. New Directions for Research

- Part 2. Politics and Law

- Part 3. Work

- Part 4. Race and Ethnicity

- Part 5. The Arts

- Suggestions for Further Reading

- Contributors

- Index