eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

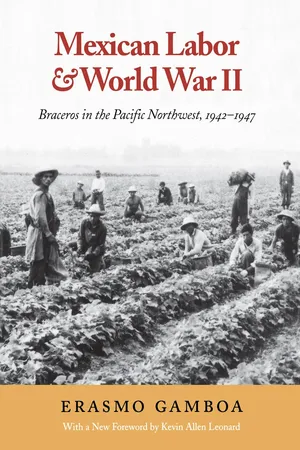

Mexican Labor and World War II

Braceros in the Pacific Northwest, 1942-1947

This book is available to read until 23rd December, 2025

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

Mexican Labor and World War II

Braceros in the Pacific Northwest, 1942-1947

About this book

"Although Mexican migrant workers have toiled in the fields of the Pacific Northwest since the turn of the century, and although they comprise the largest work force in the region's agriculture today, they have been virtually invisible in the region's written labor history. Erasmo Gamboa's study of the bracero program during World War II is an important beginning, describing and documenting the labor history of Mexican and Chicano workers in Oregon, Washington, and Idaho and contributing to our knowledge of farm labor."—Oregon Historical Quarterly

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Mexican Labor and World War II by Erasmo Gamboa,Kevin Leonard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. Agribusiness and Mexican Migration

ALTHOUGH THE Pacific Northwest is culturally different and distant from the Southwest and Mexico, Mexican people have long traveled to this region. Even so, a discernible pattern of Mexican migration did not develop until the beginning of the 1900s. Agricultural growth coupled with a liberal immigration policy toward Mexico and conditions in the Mexican Republic itself were the underlying factors that account for this migration. As the pace of agricultural development quickened during the twentieth century, many newcomers, including Mexicans, were attracted to the Northwest. The latter were immigrants residing in the Southwest and then drawn north by an incipient labor-intensive farming economy. Even during the Depression, which saw many workers sent back across the U.S.-Mexican border, northwestern farms continued to pull Mexican laborers away from many southwestern communities. Their experience in this region between 1900 and 1940 is a relatively unknown chapter in the larger pattern of Mexican immigration into the United States.

Until the 1900s, economic development in the Pacific Northwest was slow for several reasons. People considered the region to be too distant from the populated areas of the eastern United States, the road along the way arduous, and the investment in time and equipment too great. Only after the last half of the nineteenth century did yeoman farmers arrive in appreciable numbers, and even then they faced the problem of reconciling their dreams of opportunity with the geographic and economic realities of the area. Optimism in the agricultural potential of the region did not begin until the completion of the northern transcontinental railroad and the subsequent development of private and public irrigation projects.1

Once this economic infrastructure was in place, the full agricultural capability of the Pacific Northwest became evident. West of the Cascades, farmers discovered that the bottomlands of the Willamette Valley in Oregon and the Puyallup and Skagit valleys in Washington were exceptional producers of specialty crops. Not only were yields high, but they were superior in quality and commanded attractive market prices. East of the Cascades and into eastern Oregon, southern Idaho, and south-central Washington irrigation projects opened up thousands of formerly arid but rich acres of topsoil that made possible repeated yields. In other areas such as the Palouse country, wheat farmers could produce record crops without irrigation and little more than alternate fallows and sufficient winter moisture. All this should not suggest that some farmers did not hang precariously between mere indebtedness and total loss, but once the region’s agricultural potential was tapped, farm failures were few.

The Cascade Mountains determine agricultural productivity more than any other regional topographic feature. They rise abruptly from the coastal area, creating a series of fertile littoral valleys, such as the Rogue and Willamette in Oregon and the Skagit and Puyallup in Washington, and traverse Oregon and Washington in an almost true north-to-south longitude. In this coastal area, the ocean’s influence prevents either extreme cold or heat and produces a temperate climate with well-defined seasons conducive to agriculture.

East of the Cascades, the geography consists of tablelands of increasing elevation extending east into the Bitter Root Mountains of Idaho. Interspersed among these plateaus are other important agricultural valleys such as the Snake River, which runs the breadth of southern Idaho, linking several small valleys into a major agricultural belt. In Washington, proportionately smaller farming valleys such as the Wenatchee and Yakima are equally significant. As a whole these valleys receive less precipitation than the coastal area, and summer temperatures exceeding 100 degrees Fahrenheit and o or below during the winter are not uncommon.

The limitation of the agricultural-producing areas of the Northwest was, and remains, its relatively short growing season of about 180 days. Despite this limitation, irrigation and extraordinarily fertile soils made possible extraordinarily high yields of a wide variety of crops. This cornucopia of grapes, sugar beets, hops, fruit and nut trees, wheat, strawberries, beans, onions, and many other crops has led residents to coin appropriate sobriquets such as “Magic Valley” and “Fruit Bowl of the Nation” for the Boise and Yakima valleys.

Yet in spite of its comparative advantages, the success of all northwestern farming enterprises has always pivoted on an extensive supply of farm labor. Throughout the Northwest, excepting some areas along the coast, labor shortage was the most serious obstacle encountered by farmers. A combination of factors, such as low density of population, distance between populated centers and farming areas, intense oscillation between peak demand and lull, and the often arduous nature of the work itself, exacerbated an already critical problem. For these reasons, farmers used novel ways to recruit workers onto their farms and then encourage them to leave during the long winter dormancy.

When considered together, the farmers’ zeal for farming, the region’s natural advantages, and labor’s central role in agricultural production form an interesting trilogy. In a microcosm, the Yakima Valley illustrates this triumvirate feature of the northwestern farming economy.

Historically, Yakima’s combination of public and private enterprise as well as comparative natural advantages brought it early national attention as one of the country’s most important agricultural-producing areas. In 1935, Secretary of Agriculture Henry A. Wallace commented on the area’s reputation “as one of the outstanding irrigated valleys in the country and a pronounced success.”2

Yakima’s production was large but from a comparatively small valley, approximately sixty miles in length and at its breadth fifteen to twenty miles. In spite of federal reclamation projects during the Depression, Yakima County contained only 1 percent of the nation’s irrigated acreage in 1939.3 Ten years earlier, it had already ranked sixth in the nation in the value of agricultural production. Only three counties in California, one in Maine, and another in Pennsylvania stood ahead of this northwestern gem.4 Even in the midst of the Depression, Yakima Valley farms continued to rank tenth in value of production.5

One explanation for this remarkable productivity was farm management. Crop farms accounted for 80 percent of the total production, and the remainder was livestock-related.6 The crop farms were highly specialized and mostly owner-operated, because crops such as hop cultivation or fruit orchards required considerable knowledge and a high investment in trees, yards, and other capital improvements. This type of highly specialized agriculture made farmers extremely reluctant to jeopardize their investment through careless or inefficient tenant or absentee management. Even in hard times, most growers preferred to sell their farms or operate at a loss before relinquishing control. As a result and through the Depression, many farms were still in the hands of the original homesteaders or farmers. This kind of personal and not too common commitment to excellent management was a cornerstone of the valley’s outstanding production record.7

With respect to the relationship between farm labor and production, the Yakima Valley was an anomaly. In general, the farm labor needs of most agricultural economies were relative to the size of farms and the type of land tenure. Small acreage family farms, for example, generally supplied their own labor needs or called on nearby residents. Larger commercial farms, on the other hand, either absentee or family-owned, would exhaust the local work force and employ seasonal migrants. Prior to World War II, Yakima agriculture consisted primarily of small-acreage farms. Yet the demand for labor was so high and seasonal that the valley became one of the most important users of seasonal farm workers in the West. This unusual dependency on seasonal migrants had little connection with farm size and much to do with labor-intensive crops.

Hop and fruit cultivation best illustrate the shape of the labor market. In 1935, the area devoted to hop cultivation was small, approximately 5,500 acres, and required 130 man-days of labor for harvest alone.8 Conversely, the fruit acreage was considerably larger, at 54,733 acres, and the same amount of labor was sufficient for all orchard care, including harvest.9 Other variables associated with these two crops were also critical to the valley’s labor market. Since hops reached optimum maturity suddenly, farmers tended to delay the harvest as close to the ripe stage as possible. This produced an intense harvest-related labor demand that peaked quickly during three weeks in September and was over a short time later. At the point of harvest, farmers hurried the laborers because diseases or insects could rapidly devastate an entire crop, and rain or wind could just as easily fell a heavily laden yard. Fully cognizant of potential financial losses, employers generally advertised for many more workers than were necessary as a safeguard to the highly vulnerable acreage.

Fruit was not as susceptible to ruin or total loss as hops, but it had a similar swing between low and peak demand for labor. Late winter and early spring pruning resulted in a minor spurt of labor activity that was easily met by local workers. August brought the early fruit harvest and a slight need for workers that peaked in early October. Following the autumn harvest, little if any outside help was employed by fruit growers until the work cycle was repeated the following year.

Most of the Yakima farms had similar oscillations between peak labor needs and lapses. For instance, Yakima Valley agriculture needed 33,000 hired workers at the peak of the 1935 harvest. Conversely, during the winter months, from November through January, little more than 500 workers were sufficient to meet the valley’s entire labor demand.10 In other words, Yakima farmers employed sixty-six times as many workers at the September peak as they did during winter inactivity. For this reason, each year Yakima farmers faced the critical problem of recruiting large numbers of migrant men, women, and children.

The Yakima Valley was not unique; the Willamette Valley of western Oregon had many of the same characteristics: fertile soils, specialty crops, high production, and an intensive labor economy. In 1935, Willamette hop farms accounted for over half the national hop supply.11 Other area farmers raised substantial yields of vegetables, fruits, and nut crops. This outstanding capacity to produce placed the Willamette Valley second in the nation in green bean production by World War II.12 Idaho’s Upper and Lower Snake River Valley counties also yielded high quantities of specialty crops with strong market values such as potatoes, sugar beets, and peas. For instance, in 1938 potato farmers planted thirteen times less acreage than grain growers but received just slightly less than two and one-half times the value of wheat production.13 Potatoes commanded such high prices that Idaho growers raised 40 percent more than Washington and Oregon combined and twice that of California.14

Like their Yakima counterparts, Willamette and Snake River growers were confronted with the annual task of recruiting thousands of out-of-state workers. In Idaho, the sparse state population and the distance from other populated areas made the recruitment of farm labor more troublesome and, therefore, a more critical factor in production.

Labor’s role in agricultural production was critical due to other added factors. Like California, the high perishability of the area’s crops heightened the need for a large pool of farm labor. The crops’ high commercial value meant that growers required sufficient help in order to rush their crops to market at the optimum point of maturity and command the highest prices. In addition, as was pointed out earlier, in most areas several competitive labor markets—fruit and row crops—co-existed in time and space. For these reasons and others, farm labor was of strategic importance to successful farming.

From the onset this type of labor-intensive agriculture in the valleys of Idaho, Oregon, and Washington began to pull Mexican workers away from areas of the Southwest and Mexico. This process of recruitment, either directly through handbills and other advertisements or indirectly through word of mouth, invited countless numbers of Mexicans along with other groups into the region’s farming economy. Yet for reasons that will be developed later, Mexican laborers as a group did not become essential to Northwest farming until World War II. Nevertheless, because their arrival coincided with the first wave of people from Mexico, their experiences call attention to a broader interpretation of early Mexican immigration.

The combined effects of the Díaz dictatorship, the Revolution of 1910, and the absence of any real improvement in the lives of most Mexican people after the revolution gave impetus to as well as sustained the exodus of people across the U.S.-Mexican border. Between 1875 and 1910, increasing population...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Contents

- Half title

- Map: The Pacific Northwest

- Foreword

- Preface to the 2000 Paperback Edition

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. Agribusiness and Mexican Migration

- 2. World War II and the Farm Labor Crisis

- 3. The Bracero Worker

- 4. Huelgas: Bracero Strikes

- 5. Bracero Social Life

- 6. From Braceros to Chicano Farm Migrant Workers

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index