![]()

Part One

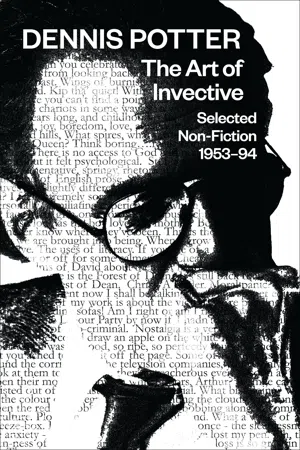

The Confidence Course

![]()

Dennis Potter once commented that ‘any writer really has a very small field to keep ploughing, and eventually you turn up the coins or the treasure or whatever it is you want.’1 He was born on 17 May 1935 in Berry Hill, in the Forest of Dean, and his lifelong contemplation and reinvention of this childhood ‘land of lost content’2 fuelled some of his greatest drama, such as The Singing Detective (1986), Stand Up, Nigel Barton (1965) and Blue Remembered Hills (1979). Potter always denied that these were truly autobiographical works, but they often reflected a version of his early life as a coalminer’s son that he told not only through his plays but also in his non-fiction and even in the personal history he portrayed to friends and colleagues.

Potter’s ‘authorized version’ of his early life was often simplified to a progression from Christchurch School, Berry Hill, to New College, Oxford, ‘giving the impression that he had gone directly from the village school to Oxford.’3 In fact, once Potter passed his Eleven Plus4 in 1946, he started at Bell’s Grammar School in Coleford, local to the Forest of Dean, and then moved on to St Clement Danes Grammar School when his family moved to Hammersmith5 in 1949. The latter had a profound influence on Potter: ‘None of the almost suffocatingly close Forest of Dean atmosphere persisted at all. That turned me very much to academic work. They said you must try for Oxford – and that seemed to me the way out.’6

St Clement Danes not only pointed Potter in the direction of Oxford, but it also gave him the opportunity to act, to become a star in the debating society, and to write for the school magazine. Potter’s first piece for The Dane, an account of a sixth-form trip, appeared in July 1952,7 and he subsequently became a regular contributor, culminating in his editorship of a literary supplement to the July 1953 issue.8 By then, Potter had already accepted a place at New College, Oxford reading Politics, Philosophy and Economics, although his arrival would be delayed by another three years owing to his failure to pass his Latin Responsions9 and the requirement to take up his National Service.

Potter’s National Service made a lasting impact on him. As well as providing rich material for his play Lay Down Your Arms (1970) and his serial Lipstick on Your Collar (1993), the posting to the Intelligence Corps Centre, Maresfield Park brought him into contact with Kenneth (later Kenith) Trodd, his future producer, collaborator and sparring partner.10 Potter and Trodd were transferred to the Joint Services School for Linguistics in Bodmin in order to learn Russian, after which they were posted to MI3 in the War Office. The work was stultifying, and even after Potter was discharged in October 1955, he still had another year to kill before going up to Oxford, and so passed the time working at the Meredith & Drew biscuit factory in Cinderford. By the time he finally arrived at Oxford in 1956, he was formidably well read, and anxious to make his mark.

Potter’s time at Oxford was both exhilarating and fraught as he battled his way to most of the influential positions available to him: editor of Isis,11 editor of Clarion12 and Chair of the University Labour Club. Only the position of President of the Oxford Union eluded him, but he created more controversy and garnered more national press than any of his contemporaries. Whether accusing his rival Brian Walden of electoral malpractice,13 confronting the owners of Isis,14 or taking on Special Branch,15 Potter was rarely out of the newspapers. This success deepened his preoccupation with class, and his thoughts on the issue were given shape by Richard Hoggart’s influential 1957 book The Uses of Literacy.16

Hoggart’s work inevitably struck a chord with Potter, as it described the vibrant working-class culture of the recent past and its transformation into a spiritless, commodified and commercialized existence. The book also made specific reference to the difficulties faced by scholarship boys as they traversed the class divide. Another influence on Potter was the concept of Admass, a word coined by J.B. Priestley and Jacquetta Hawkes to describe ‘the whole system of an increasing productivity, plus inflation, plus a rising standard of material living, plus high-pressure advertising and salesmanship, plus mass communication, plus cultural democracy and the creation of the mass mind, the mass man.’17 It is hard to overstate the importance of this idea to Potter, and he returned to it regularly in his non-fiction throughout his life. In the short term however, these influences drove Potter in a way that gained him even greater student fame, and some measure of notoriety.

In May 1958, the New Statesman published Potter’s article “Base Ingratitude?”,18 which revisited concerns about class that he had addressed on a number of occasions in his earlier pieces for Isis, and which were further honed by the influence of Hoggart. The article drew the attention of Jack Ashley, a producer at the BBC who invited Potter to contribute to a series that would eventually become Does Class Matter?19 Potter’s interview for the programme focused on his difficulties negotiating the differences between his new life in Oxford and family life back in the Forest of Dean, and he later came to regret some of his comments such as ‘my father is forced to communicate with me almost, as it were, with a kind of contempt.’

The Reynolds News pre-empted the transmission with a lurid headline – “Miner’s son at Oxford felt ashamed of home” – and Potter considered a libel action such was his anger at the accompanying article. However, he subsequently used a similar scenario in his play Stand Up, Nigel Barton and later admitted that he’d betrayed his parents and ‘been a shit, and mea culpa.’20 The interview also caused controversy in the pages of his local newspaper the Dean Forest Guardian, for which Potter had previously written, and so he once again took to the pages with a strongly argued defence of his conduct.21 These trials and tribulations were grist to the mill of his many enemies in Oxford, who reported gleefully that the ‘natives had been enraged.’22 However, Potter learned at this point that attention from the press is a double-edged sword, as despite the heartache at home, the high profile that resulted from various Oxford altercations and his television appearance had brought him a book commission,23 and an informal offer of a job at the BBC once he had taken his degree.24 His subsequent career reflected this early pattern – various controversies boosted his profile and gave him great opportunities, but often at a cost.

Potter joined the BBC as a general trainee in July 1959, and although accounts vary as to his initial postings,25 he was eventually transferred to Panorama (BBC, 1953–) on attachment to Robin Day. Despite seemingly following a typical path into the Establishment, from Oxford to the BBC, Potter was no ordinary trainee. His book The Glittering Coffin26 – a strident summation of his views on class and Admass culture – had marked him out as an ‘Angry Young Man,’ despite his protestations to the contrary,27 and its serialization in the Daily Sketch as “What’s eating Dennis Potter?”28 again showed his willingness to seize upon the popular press as a vehicle to get his ideas across to the widest range of people. He quickly, and perhaps unwisely, persuaded the Panorama team to run a feature on the state of mining in the Forest of Dean,29 and after he was sent on attachment to documentary maker Denis Mitchell,30 he and producer Anthony de Lotbiniere set to work on Between Two Rivers (1960),31 a half-hour documentary about the Forest of Dean which caused yet more controversy in the pages of the Dean Forest Guardian.32

Only a couple of months after the transmission of Between Two Rivers, Potter tendered his resignation to the BBC,33 ostensibly because he had been commissioned to write The Changing Forest,34 but also because he feared that his political work would continue to bring him into conflict with the Corporation. His resignation also gave him the opportunity for freelance work as a writer on a planned BBC book series that eventually reached the screen in October 1960 under the title Bookstand.35 The series attempted to make ‘difficult’ novels accessible, and Potter was responsible for dramatizing sequences from the featured novels. The Director-General Hugh Carleton Greene disapproved of these extracts and frowned upon the series,36 but the Bookstand staff ‘were trying to make [the programme] speak to non-book-readers’37 as well as the usual literary audiences.

The desire to communicate beyond a narrow cultural elite had preoccupied Potter during this period, and he returned to the work of Raymond Williams, another writer, like Hoggart, who was one of his major influences at University. Potter was particularly interested in Williams’s concept of a ‘common culture’ that could reach across the class divide.38 When Potter later reviewed Williams’s novel Border Country for the New Left Review, the book, which featured a London-based university lecturer returning to his working-class home in Wales, had obvious resonances for him, particularly in light of the furore around Between Two Rivers. This caused him to reflect that ‘when I think back to the arguments at home, the genuinely desperate attempts to force comprehension of at least some part of the things I felt after going up to Oxford […] I do not feel very happy. But, writing this now in the Forest, I do not want to go on and on in this fashion, and […] I know that it has made me take stock of my own position…’39

Although Bookstand continued, the dramatized sequences were dropped, which left Potter out of a job. He had married while still at Oxford, and now also had a family to support, so he accepted with alacrity when offered a job at the Daily Herald,40 a Labour-leaning newspaper. Initially he was a reporter-at-large, but his work became hampered when he first displayed symptoms of what was to become a lifelong condition: psoriatic arthropathy.41 He was first hospitalized in June 1962, and shortly afterwards he took over the role of television critic for the Daily Herald.42

It was during this period that Potter became immersed in what Raymond Williams would later call the ‘flow’ of television.43 His Herald column covers every kind of programme, from light entertainment to Panorama by way of Compact,44 Emergency – Ward 10,45 Sportsview,46 and the antics of Hughie Green.47

Potter’s daily column was ‘phoned in’ the previous night meaning that only peak-time programmes were reviewed, although he rapidly picked up an additional, more expansive column on Saturdays where he had the opportunity to revisit a show at greater length. Although his time at the Herald generally produced rather slight pieces, it was a formative period. Potter had seen the potential of television as a teenager: ‘Here was a medium of great power, of potentially wondrous delights, that could slice through all the tedious hierarchies of the printed word and help to emancipate us from many of the stifling tyrannies of class and status and gutter-press ignorance’48 and during his years as a television critic, with Raymond Williams’s ‘common culture’ in mind, it seems that Potter became convinced of television’s potential as a democratic medium.

The Herald years also helped Potter’s career in more practical ways. He favourably reviewed49 the BBC’s new satire show That Was the Week That Was (1962–63), popularly known as TW3, and David Nathan, his colleague at the Herald, managed to sell producer Ned Sherrin a gag during an interview. Nathan and Potter subsequently teamed up, and wrote a number of sketches for TW3 and its successor Not So Much a Programme More a Way of Life (BBC1, 1964–65), as well as contributing to various shows at The Poor Millionaire satire club.50

By this time, Potter had been selected as a Labour candidate for East Hertfordshire, and was actively seeking a career in politics. Also of concern during this period was his health: the psoriatic arthropathy became more severe, leading to spells of hospitalisation and a growing realisation that his choice of career might be limited by his lack of mobility.

1964 was a crucial year for Potter. The Daily Herald closed down and was reborn as the Sun51 shortly before Potter unsuccessfully stood as a candidate in the October General Election.52 Although he briefly worked as leader writer for the Sun around the time of the election, he resigned shortly afterwards, and left payroll journalism for good. However, he already had the makings of another career. Earlier in the year, Potter had been commissioned to write his first television play The Confidence Course (1965)53 and also a play based on his experiences duri...