- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Service design is a rapidly growing area of interest in design and business management. There are a lot of books on how to get started, but this is the first book that describes what a 'good' service is and how to design one. This book lays out the essential principles for building services that work well for users. Demystifying what we mean by a 'good' and 'bad' service and describing the common elements within all services that mean they either work for users or don't.A practical book for practitioners and non-practitioners alike interested in better service delivery, this book is the definitive new guide to designing services that work for users.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Good Services by Lou Downe in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Consumer Behaviour. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

15 principles of good service design

1

A good service is easy to find

The service must be able to be found by a user with no prior knowledge of the task they set out to do. For example, someone who wants to ‘learn to drive’ must be able to find their way to ‘get a driving licence’ as part of that service unaided.

The first step in providing a good service is making sure that your user can find your service. This might sound simple, but it’s a lot harder to do than it sounds.

Staff at a small rural UK county council discovered this to their horror in late 2016 when, after opening their information desk at 9am on a Tuesday, they were approached by a man carrying a dead badger. The man slammed the badger down on the desk, much to the shock of the customer services manager, proclaiming that he had found it outside of his house, and didn’t know what to do with it. ‘I tried looking on the website,’ he said. ‘But I couldn’t find “dead badger” on the list, so I came here.’

Not every situation is as hard to figure out as what you need to do when disposing of a dead animal. After all, it’s not something that happens every day. However, just as the man with the badger did, your users will come to your service with a preformed goal that they want to achieve. This can be very simple, like ‘dispose of a dead animal’ or ‘learn to drive’ or ‘buy a house’.

Where your user starts will depend on how much they’re already aware of what services might be available to meet their needs. Your job is to make sure that they can get from this goal to the service you provide, without having to resort to support. Or dropping off a dead badger at reception.

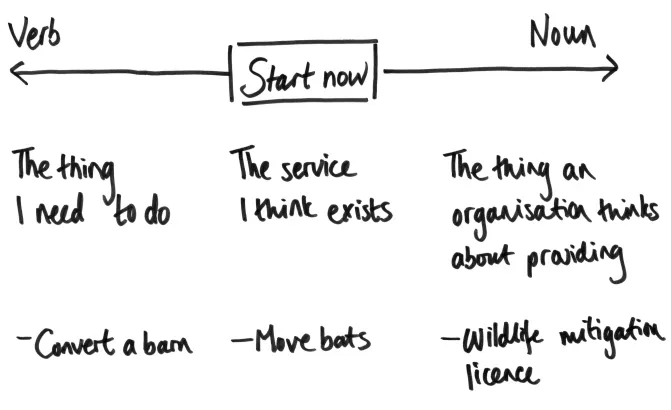

To a user, a service is simple. It’s something that helps them to do something – like learn to drive, buy a house or become a childminder. This means that, to a user, a service is very often an activity that needs to be done. A verb that comes naturally from a given situation, which will more than likely cut across websites, call centre menus and around carefully placed advice towards its end goal. The problem is, this isn’t how most organisations see their services. For most organisations, services are individual discrete actions that need to be completed in a specified order – things like ‘account registration’, ‘booking an appointment’ or ‘filling a claim’.

Because these isolated activities need to be identifiable for the people operating them, we’ve given them names, nouns, to help us keep track of them and refer to them internally. Over time these names become exposed to users, even if we don’t mean them to be initially.

In government, these are things like ‘Reporting of Injuries, Diseases and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations 1995 (RIDDOR)’ or ‘Statutory Off Road Vehicle Notification (SORN)’ – but the names private organisations give these things are no less obtuse. Names like ‘eportal’ or ‘claims reimbursement certificate’ are commonplace in the private sector.

Good services are verbs

Bad services are nouns

Google is the homepage of your service

Without understanding what our users are trying to achieve, and reinterpreting our services in language that our users can understand, we often place users in a situation where, to find something, they need to know exactly what they’re looking for. For a user to find a service like RIDDOR or SORN, they first need to know what you call your service, resulting in an additional step being added to your service – that of learning the name that your organisation calls the thing they’re trying to do.

As with the case of the dead badger, the less you know about the situation you’re in, the support available to you or what you should do, the harder you will find this search. Needless to say, even the most patient people wilt at the prospect of this almost impossible task. Instead their confusion drives to them to call centres or, worse, they won’t use your service at all.

Google is the homepage for your service. Whether your service is usable online or not, this is likely to still be the way that it will be found and accessed. When it comes to finding your service, nothing is more important than its name. Beyond making it easier for search engines to index and list your service, the name of your service makes a statement to your user about what that service does for them.

The UK Ministry of Justice found this out when they set about changing its Fee Remissions service in 2017. The Fee Remissions service helps to pay for or subsidise the cost of court fees for people who aren’t able to pay themselves. However, it doesn’t take a genius to realise that the word ‘remission’ is not the most frequently used word, particularly in a financial content. Given that the financial literacy of those applying often wasn’t high, the title of the service was not only hard to understand for most people, but served to weed out precisely the users who were eligible to use it.

The reason this happened is simple, and happens every day in the creation of services. The title of the policy, somewhere long ago, had simply been made into the name of the service, without a thought to what language a user might use.

Nouns are for experts

Verbs are for everyone

Several rounds of research with the users of the service and staff providing it revealed that it was often referred to as ‘help with court fees’ rather than ‘fee remissions’, so the team renamed the service, meaning that users with low levels of financial literacy were able to use it.

When we design services with noun-based names like ‘Fee Remission’, we are designing them for use by experts, something that worked well when services were provided by trained expert humans, but means that they don’t work unassisted on the internet.

Instead we often find that other professionals willingly offer support to our users – at a cost. This happened with Fee Remissions, as it so often does with many of the more obtuse services, from insurance buying to visa applications – when several third-party providers offered their services in helping users apply for what should have been a free service.

In the past, we used advertising to ‘educate users’ in our nouns, forcing the kind of brand familiarity that came naturally to well-used objects like Sellotape, Hoovers or Biros. But unless you’re confident that you will get the kind of market ubiquity that comes from being a household name (and this happens to fewer companies than you’d think), your service is likely to be one of the thousands a user will use infrequently or once in their lives.

Equally, if you’re a household name that has more than one service, this tactic is out. Your users still need to be able to sift through the many things you do to find the one thing that they need, and they aren’t going to be able to do that if you’ve got a jumble sale of nouns to wade through.

Naming your service

Rather than using the words your organisation uses to describe the tasks it has completed, try to find out some of the words your user would use to describe what they’re trying to achieve. What names work for users will depend on two things:

1What your user wants to achieve

2How knowledgeable they are about what services might be available to help them achieve their end goal

For example, someone moving house might not think that the service ‘move house’ exists, based on their previous experiences, but instead might think to look for ‘removal companies’ or ‘estate agents’.

In areas where a service is less ubiquitous than moving house – for example, registering a trademark – a user’s knowledge of what they might be able to get help with might be so low that they may try to find the noun they think most applies to them and hope for the best. This obviously means they may end up using a service that isn’t applicable to them. Your job is to understand how that overall task breaks down into smaller tasks a user identifies as something they need help with.

It might help to think about the name of your service existing somewhere on a spectrum between verb and noun, where the thing users think to look for will inevitably be somewhere in the middle. Most importantly, base your name on a solid understanding of the words your users use.

1Avoid legal or technical language

For example, rather than ‘fee remission’ use ‘help with payment’.

For example, rather than ‘fee remission’ use ‘help with payment’.

2Describe a task, not a technology

Avoid words that describe a technology or an approach to technology that your service uses, such as ‘portal’, ‘hub’ ‘e-something’ or ‘i-something’. Your approach to technology is rarely of interest to your user, and words like these only serve to date your service to a particular era of technology.

Avoid words that describe a technology or an approach to technology that your service uses, such as ‘portal’, ‘hub’ ‘e-something’ or ‘i-something’. Your approach to technology is rarely of interest to your user, and words like these only serve to date your service to a particular era of technology.

3Don’t use acronyms

Acronyms might make it easier for you to refer to your service, but they are the most impenetrable language for your user to decipher.

Acronyms might make it easier for you to refer to your service, but they are the most impenetrable language for your user to decipher.

When searching for a service, what users look for is somewhere on a spectrum between what your organisation calls your service and what your user needs to do.

Changing what you call your service will change what it does

Most importantly, changing the name of your service might sound like a small thing, but aside from the huge effect on your immediate users, it will have a big effect on what your service does and how it operates in the long term.

Seeing your service as ‘stop paying tax on a vehicle’ instead of ‘SORN’ subtly shifts the purpose of that service closer to what a user understands as its purpose and the language your organisation uses to talk about it.

In summary

1When it comes to finding your service, nothing is more important than its name

2The name should reflect what users are trying to do

3Use words that your users will understand

2

A good service clearly explains its purpose

The purpose of the service must be clear to users at the start of using the service. That means a user with no prior knowledge must understand what the service will do for them and how it will work.

One of the easiest mistakes people make when they’re telling a story is to forget the beginning.

We’ve all been there; we’re sat in a bar with a friend, or watching a colleague give a presentation, and we realise halfway through the story they’re telling that we have no idea what it is they’re talking about. They’ve missed out where they were, who they were with or a vital fact that the whole story hinges on.

It’s an easy mistake to make, often because the audience we’re talking to is familiar, and we presume a piece of prior knowledge from them that they don’t have. The more familiar the audience, the more likely we are to forget.

The same goes for servi...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Forewords

- What is a service?

- What makes a good service?

- The 15 principles of good service design

- Principle 1 Be easy to find

- Principle 2 Clearly explain its purpose

- Principle 3 Set a user’s expectations of the service

- Principle 4 Enable each user to complete the outcome they set out to do

- Principle 5 Work in a way that is familiar

- Principle 6 Require no prior knowledge to use

- Principle 7 Be agnostic of organisational structures

- Principle 8 Require the minimum possible steps to complete

- Principle 9 Be consistent throughout

- Principle 10 Have no dead ends

- Principle 11 Be usable by everyone, equally

- Principle 12 Encourage the right behaviours from users and service providers

- Principle 13 Quickly respond to change

- Principle 14 Clearly explain why a decision has been made

- Principle 15 Make it easy to get human assistance

- End note

- Copyright

- Back Cover