- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Why have South-East Asian countries like Malaysia, Indonesia and Vietnam been so successful in reducing levels of absolute poverty, while in African countries like Kenya, Nigeria and Tanzania, despite recent economic growth, most people are still almost as poor as they were half a century ago? This book presents a simple, radical explanation for the great divergence in development performance between Asia and Africa: the absence in most parts of Africa, and the presence in Asia, of serious developmental intent on the part of national political leaders.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Asia-Africa Development Divergence by David Henley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Development Economics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 | DIVERGING PATHS

Fifty years ago when the colonial empires ended, most of the globe, including the Asian as well as the African tropics, was inhabited by peasantries facing very low living standards. Since then, the tropical world, the South, has diversified into a wide spectrum of development outcomes. On the one hand, there are successful countries with export-oriented manufacturing industries and productive, commercialized agricultural sectors. At the other end of the spectrum are countries where, despite increasing urbanization, subsistence farming still forms the backbone of the economy, and where the only significant export industry is oil or mineral extraction. While the successful developers have experienced vast improvements in living standards, many of the countries left behind are still almost as poor as they were fifty years ago.

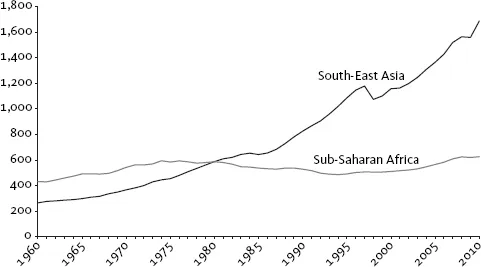

The reasons for this great divergence are of obvious importance to everyone concerned with development and development cooperation today. This book sets out to investigate them in the context of the two regions of the world which most clearly exemplify the diverging paths to prosperity and poverty: South-East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa (Figure 1.1). The present chapter introduces some basic data and briefly summarizes my main arguments and conclusions. For more detail on any point, readers are referred to the more complete information and argumentation presented in subsequent chapters.

In South-East Asia the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s all saw sustained and accelerating economic growth. By the 1990s only Burma, among the major countries of the region, was still missing out on what was acclaimed as an Asian development miracle (World Bank 1993). Although the financial crisis of 1997–98 revealed vulnerabilities in South-East Asia’s economies, it only very briefly halted their expansion. In Africa, by contrast, such dynamism remained absent. By the early 1990s even those few African countries where security and policy conditions had long been considered promising, such as Kenya and Côte d’Ivoire, were falling into the continental pattern of instability and stagnation. Scholars identified a negative ‘African dummy’ as a statistical predictor of comparative economic performance (Barro 1991), and counterposed an African ‘growth tragedy’ to the Asian miracle (Easterly and Levine 1995).

1.1 Sub-Saharan Africa and South-East Asia

Since the late 1990s there has been sustained growth in national incomes in Africa due to improved macroeconomic policies and liberalization of markets, together with increased world demand for minerals, coffee, cotton and other primary products. But by most accounts, there is little sign yet of this rapid aggregate growth translating into comparably rapid poverty reduction. If poverty is still present among marginal and dispossessed groups in South-East Asia, in Africa it is still the norm. And whereas the bulk of South-East Asian exports now consists of manufactured goods, Africa still manufactures almost nothing which the rest of the world wants to buy. South-East Asia, to complete the irony, has outstripped Africa even in the export of traditional African agricultural products such as palm oil, coffee and cocoa.

Historically, both regions formed part of the world’s economic periphery, exporting forest products (spices, ivory) and later commercial tree crops, and importing manufactures. At the local level their economies were subsistence-oriented and their societies organized on a peasant or tribal basis, often without educational or business institutions of indigenous origin. Commerce, in both regions, was associated with trade-specialized ethnic minorities – historically often Islamic, later also Asian (Indian/Chinese) and European. Over large parts of South-East Asia as well as most of Africa, indigenous state formation was limited prior to colonial intervention. In the middle of the twentieth century, both regions were still substantially under European rule. Climate and soil conditions in both regions are generally problematic for arable farming, and people and livestock are subject to similar health problems.

These historical and geographical similarities make the comparison of South-East Asia with sub-Saharan Africa a sharp tool for the analysis of development issues. Insofar as the research on which this book is based has precedents, they have most often involved the comparison of Africa with economically successful Asian countries in general, including Taiwan, South Korea and even Japan (Lawrence and Thirtle 2001; Lindauer and Roemer 1994; Nissanke and Aryeetey 2003a; Stein 1995a). But North-East Asia, by almost any measure, was already much more different from Africa fifty years ago than was South-East Asia: better governed, more educated, more industrialized (Booth 1999, 2007). In analytical terms, selecting South-East Asia as the unit of comparison helps to reduce the number of potential explanations for the observed developmental divergence. By the same token South-East Asia’s policy experience, as the World Bank’s East Asian Miracle study rightly noted (1993: 7), is more relevant than that of North-East Asia to other developing countries, including those of Africa.

Another good reason for comparing Africa with South-East Asia is that since the 1960s both regions have been characterized by corruption and a notorious lack of ‘good governance’. Certain features of African politics which are often said to explain economic stagnation in Africa (Chabal 2009; Chabal and Daloz 1999; Van der Veen 2004; Van de Walle 2001) are also present in economically successful South-East Asia. In both regions, rent-seeking is common in government positions in connection with what has been called ‘neo-patrimonialism’: a fusion of public and private spheres in which patron–client relations structure political behaviour. Some of the same cultural phenomena currently blamed for development failure in Africa, including a preference for personalistic power relationships, have been equally pervasive aspects of the South-East Asian political scene (Robison and Hadiz 2004; Scott 1972). In South-East Asia, some have even argued, patron–client ties between politicians and businessmen may serve precisely to facilitate economic development (Braadbaart 1996; Khan and Jomo 2000).

Corruption and clientelism, then, cannot in themselves explain African economic retardation. Correlations between indices of ‘good governance’ and economic growth rates, as Mushtaq Khan (2007: 8–16) has shown, all but disappear once already rich countries are excluded from the database. Among developing countries, those with rapidly growing economies hardly differ from slow growers in terms of corruption and institutional quality (Wedeman 2002).

Some authors have tried to qualify this observation by distinguishing between ‘organized’ (Asian) and ‘disorganized’ (African) forms of corruption, the former being centralized and predictable and the latter competitive, unpredictable and incompatible with growth (Lewis 2007; Kelsall 2013; Macintyre 2001). On close inspection, however, this distinction is not entirely convincing either, since some African countries have seen long periods of political stability during which illicit rents have been centrally managed by dictators or tight-knit ruling oligarchies. A particular aim of this book is to take issue with the influential school of thought which ascribes developmental failure in Africa to the ways in which political power is organized on that continent, as opposed to the ways in which it is used (Bates 1981, 1983; Lewis 2007; Ndulu et al. 2008; Van de Walle 2001). I argue that the great developmental divergence of the last fifty years between Africa and South-East Asia has been caused first and foremost by differences in the policy choices of governing elites, and that in both regions, as Bannerjee and Duflo (2011: 271) also conclude in their book Poor Economics, ‘it is possible to improve governance and policy without changing the existing social and political structures’.

Accordingly, this will be a book on development in which the voices of the historical actors who have actually made development policy in practice, and of contemporary eyewitnesses to the policy-making process, will take precedence over the voices of academic commentators on development. While theoretical debates are certainly not ignored, politicians and planners whose decisions have influenced the development trajectories of their countries will be quoted as often and extensively as will canonical writers in the field of development studies. In my view it is the first-hand experience of key historical decision-makers which provides the best insights not only into which policies work and do not work, and why, but also into the reasons why particular policies are chosen, or not chosen, in particular times and places.

Scope of the divergence

In 1960, South-East Asians were on average much poorer than Africans; by 1980 they had caught up, and by 2010 they were two and a half times richer. In South-East Asia the whole of the intervening half-century was a period of almost continuous growth, apart from a brief hiatus at the turn of the century caused by the Asian financial crisis. In Africa, per capita income stagnated in the 1970s, declined in the 1980s, grew weakly in the 1990s, and in 2010 was still barely higher than it had been in 1975 (Figure 1.2).

The recent aggregate growth in Africa has caused the ‘Afro-pessimism’ of the 1990s to be replaced in some circles by a conviction that the Asian tiger economies are now being joined by a fast-developing group of ‘African lions’ (McKinsey Global Institute 2010; Radelet 2010). But there is a vital difference. Although some researchers believe that recent progress in African poverty reduction has been underestimated (Sala-i-Martin and Pinkovskiy 2010), the consensus is that the aggregate growth in Africa since the 1990s, like that of the 1960s and 1970s, has not translated into commensurate reductions in poverty (OECD 2011: 12, 62–5; UN Economic Commission for Africa 2011: 3).

1.2 South-East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa: GDP per capita (constant 2000 US$), 1960–2010 (source: calculated from online World Development Indicators/World DataBank, World Bank)

In South-East Asia, by contrast, spectacular economic growth from the 1960s onward was accompanied by even more spectacular reductions in poverty. In Thailand the proportion of the population living below the national poverty line fell from 57 per cent in 1963 to 24 per cent in 1981 (Rigg 2003: 99); in Malaysia, from 49 per cent in 1970 to 18 per cent in 1984 (Crouch 1996: 189); in Indonesia, from 60 per cent in 1970 to 22 per cent in 1984 (BPS-Statistics Indonesia et al. 2004: 13); and in Vietnam, even more dramatically, from 58 per cent in 1993 to 19 per cent just eleven years later in 2004 (Nguyen et al. 2006: 9). In 2005, according to World Bank and United Nations figures, the proportion of South-Ea...

Table of contents

- Cover

- About the Author

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Figures and tables

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Diverging Paths

- 2 Studying the Divergence

- 3 Setting the Stage for Development

- 4 Agrarian Roots of Development Success

- 5 Varieties of Rural Bias

- 6 Elements of the Developmental Mindset

- 7 Origins of the Divergence

- References

- Index