![]()

1

“Boomerang”

Hip-Hop and Pan-African Dialogues

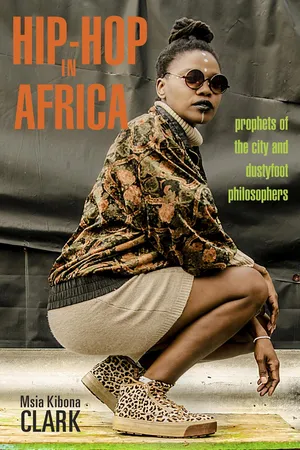

HIP-HOP CULTURE IN Africa has increasingly been a subject of research that recognizes the importance of the culture’s popularity and its potential for influencing change. It is a culture that has had a tremendous impact on youth in Africa. Like hip-hop in the United States, hip-hop in Africa has had transformative impacts on youth. It has become more than just a style or genre of music. It is a culture that is simultaneously connected to global hip-hop cultures and local cultural systems. Hip-hop in Africa has brought African voices to a global hip-hop community. Hip-hop in Africa is a representation of African realities and of African youth cultures. In essence, hip-hop in Africa provides its own record of historical and contemporary Africa, a record no less significant than a written text, a documentary film, or oral histories. The subtitle of the book, Prophets of the City and Dustyfoot Philosophers, refers to the role of emcees in local cityscapes, their roles as prophets and philosophers narrating their local urban spaces. Prophets of the City is also an homage to the pioneering South African hip-hop group Prophets of da City, while Dustyfoot Philosophers is an homage to the landmark album The Dusty Foot Philosopher by Somali rapper K’naan.

In understanding both historical and contemporary Africa, one can look to its music. The concept of cultural representations in cultural studies asserts that to understand any society or culture one “must understand the practices that surround the production and consumption of its music” (Ingram 2010, 106). While the focus of this research is primarily the music, music is not the only form of cultural representation. Written text, song, poetry, film, television, fine art—all are cultural representations. The concept of cultural representation is found within cultural studies and was advanced by scholars such as Stuart Hall. According to Hall (2013), there are the “reflective, the intentional and the constructionist approaches to (cultural) representation.” Cultural representations may reflect what is going on in society, they may be an expression of the creator’s intentions, or they may construct meaning for the audience consuming the representations. This research takes a more constructionist approach, looking at how hip-hop, as a cultural representation, constructs certain narratives for its audiences.

This research focuses on the importance of cultural representations (hip-hop) in constructing understandings of political institutions, social change, gender, migration, and identity in Africa. Most of what we know about the world is through “mediation,” or representations, whether it be a newscast, a textbook, or a film. These representations can come in the form of a blog, a website, Twitter, a Facebook post, or a YouTube video. When we take in these representations by watching, listening, reading, and experiencing; reality is being shaped (Ingram 2010; Barker 2012). Cultural representations, in this case hiphop, shape how the consumers of those representations view society and what realities they adopt.

When news directors at the BBC, CNN, or Al Jazeera reduce the day’s events to thirty- or sixty-minute segments, they shape how viewers interpret the world (Barker 2012). Truth and reality are not neutral but constructed. As a form of cultural representation, hip-hop is no different. The artists themselves decide what is relevant and what realities they want to construct. Whatever is produced—be it music, a graffiti tag, a graphic design on a T-shirt, or a film—the cultural production encompasses the ideologies and backgrounds of the artist(s). Participants and observers of African hip-hop facilitate the process of creating reality by defining what information is important and interpreting it based on their own social, cultural, and ideological perspectives. The street language used in hip-hop, for example, may cause some to dismiss the music as troublesome, and disrespectful, while others may be drawn to the music because they feel connected to the words being spoken.

For the purpose of this research, African hip-hop will include hiphop music performed by individuals born in Africa, and who identify as African, regardless of where they live. The definition will also include those who are recent African migrants as a result of migrations of African communities outside Africa, especially in the West, in the past fifty years. While there are African hip-hop artists all over the world, this research will focus primarily on hip-hop in Africa, as well as hip-hop produced by those who migrated from Africa to the United States, the birthplace of hip-hop culture.

While the concept of representation is often discussed by hiphop artists, it is also a core concept within cultural studies. According to Hall, “To say that two people belong to the same culture is to say that they interpret the world in roughly the same ways and can express themselves . . . in ways which will be understood by each other” (2013). Hip-hop music speaks, through the use of shared languages, to individuals within certain cultures. Hip-hop is a vehicle by which artists represent locations, experiences, and identities. It is also a vehicle through which African realities are shaped and told. Representation in hip-hop serves to validate, depict, and define a place, a people, and experiences.

This research contributes to defining African hip-hop and recognizes hip-hop culture in Africa as a form of cultural representation by urban youth on the continent and in the diaspora. African hip-hop culture is tied to both African cultures and global hip-hop cultures. Hip-hop uses the power of words and wordplay while simultaneously understanding and harnessing the power of representation.

The research is based on the premise that hip-hop is a musical form with African roots, roots that predate hip-hop’s contemporary origins in the South Bronx between 1970 and 1973 (Chang and DJ Kool Herc 2005; Kitwana 2002). Hip-hop is part of years of back-and-forth music flows between Africa and the African diaspora. African hiphop has also been influenced by the continent’s own musical history. Hip-hop artists all over Africa have used local, continental, and diasporic elements in their music.

The research will examine representations within this varied and complex culture, on a continent with multiple hip-hop communities. Some hip-hop communities are larger than others. Most began in the capital cities but have spread to smaller towns and villages. There are also a growing number of African artists in the US diaspora, as a result of the large numbers of Africans who have migrated out of Africa and into the United States in the past thirty years. Hip-hop is bringing these artists together through collaborations and is creating both diverse and common narratives of African society.

This book examines the role that female artists play in constructing contemporary representations of African women. These artists are influenced by both hip-hop and local cultures, and they use their music to provide additional perspectives on, and depictions of, women in Africa. Many challenge constructions of femininity and womanhood, or the policing of women’s sexualities. Others direct their commentary toward gender oppressions or gender identities. It is important to understand how the representations created by female emcees contribute to our understandings of urban African women. Media representations of African women present skewed single-story narratives of passive, poor, rural African women. Female emcees offer representations that present narratives of African women having agency, women in both urban and rural contexts, and women who recognize and grapple with privilege in its many manifestations.

The research looks at African hip-hop as a representation of African society, as a representation through which Africa is discussed, defined, and represented. The events and experiences that have influenced the content of hip-hop in Africa, and the representations of Africa it chooses to depict, are significant. These events and experiences differ across Africa, but there are some important similarities. For example, the depictions of African economic and political realities, interactions with state institutions, and access to resources bear significant similarities in hip-hop coming from various parts of Africa. Topics like migrations west, across the Sahara, and in boats, as well as via Western embassies in search of visas, are depicted in a similar way across the continent by both anglophone and francophone artists.

As part of the global hip-hop community, African hip-hop artists have advanced the culture artistically and have created new spaces where Africans are able to tell their stories. In its examination of hiphop in Africa, this study will also illustrate the transition artists have made from providing political commentary and protest music to actually becoming agents of social and political change. As the increase of youth mobilization globally has resulted in popular uprising, the roles played by hip-hop artists and hip-hop culture in specific countries need to be understood as having local and global significance.

The Pan-African Connection

In 2003 the Senegalese rap duo Daara J released an album entitled Boomerang, based on the premise that when Africans left the continent in bondage during the transatlantic slave trade, they took with them their musical traditions, which evolved into hip-hop, which returned to Africa in the 1980s. These music traditions that were taken with enslaved Africans developed and were cultivated on the plantations of the Americas and included drumming, rapping, and storytelling (Keyes 2008; Manning 2009; Appert 2016). Over time, African American culture incorporated these music traditions into new forms of African American music and self-expression.

Hip-hop’s roots in African culture have been discussed in three major ways: by linking hip-hop music to African rhythms and drumbeats, by linking modern rapping to traditional African forms of rapping or poetry, and by drawing parallels between the hip-hop emcee and the West African griot.

Robert Walser (1995) looks at the “percussive sounds, polyrhythmic texture, timbral richness, and call-and-response patterns” found in hip-hop and links them to origins in Africa. Cheryl Keyes (1996) also looks at the continual repetition of particular rhythms in African music, which are similar to the hip-hop DJ’s tradition of repeating and extending the playing time of parts of a song, while mixing in the next song. Keyes says this “reaffirms the power of the music” and creates a connection with the listener (1996, 236). This is manifest in the call-and response traditions practiced at hip-hop performances. Walser’s (1995) article shows similarities in rhythms and beat patterns found in African and hip-hop music, specifically the polyrhythmic nature of both. Music is polyrhythmic when it contains two or more conflicting rhythms at the same time. Many early hiphop drumbeat patterns have similarities with patterns found in many African drumbeats.

Lyricism with rhyme styles similar to those found in hip-hop lyricism can also be found in some African languages. Keyes says hip-hop rapping can be traced from “the African bardic traditions to the rural oral southern-based expressive forms of African Americans” (2006, 225). The language most often cited as having a form of rap is Wolof and the tradition of tassou. Tassou is a form of rapping that is often accompanied by drumming and is found in Senegal and the Gambia (Tang 2007; Gueye 2011; Penna-Diaw 2013; Appert 2016). In other countries, like Somalia and Tanzania, artists have reflected on associations between rap and poetry.

The role of the emcee as a griot has also been discussed by scholars, who point to American hip-hop artists as being among the first to draw the parallels. Hip-hop pioneer Afrika Bambaataa, Professor X (a member of the 1990s rap group X-Clan), Nas, and Kanye West have all referred to themselves as griots (Tang 2012; Kimble 2014). Scholars who discuss the parallels between the rapper and the West African griot point to the griot’s role in their community as a storyteller and historian (Smitherman 1997; Dyson 2004; Tang 2012; Sajnani 2013; Appert 2016). While Sajnani’s (2013) article reflects on the griot’s position among the elite to debunk this connection, the similar functions the griot and the emcee play in their societies remain evidence for many of the connections between the two roles. The collaborative nature of African music and the traditions of call-and-response are also used to point to relationships between hip-hop and African music. A lot of African music is collaborative music, similar to the cyphers, sessions, and battles that take place in hip-hop culture.

In the twentieth century the African music traditions that were present in the African American community would merge with African-influenced Caribbean sounds as an increasing number of Caribbean immigrants arrived in the United States (Kalmijn 1996; Foner 2001). With similar patterns of music retention, the Caribbean population that would emerge in New York City was large. It would be members of that Caribbean community who would collaborate with African Americans to create a cultural revolution. The music that would develop into hip-hop has its roots in these retained musical traditions.

Hip-hop emerged in the Bronx borough of New York City in the 1970s, where African American residents exchanged creative influences with the West Indian and Puerto Rican communities (Chang and DJ Kool Herc 2005). Caribbean immigrant artists such as Jamaican-born DJ Kool Herc (Clive Campbell), Barbadian-born Grandmaster Flash (Joseph Saddler), and Antiguan-born DJ Red Alert (Frederick Crute) were among the pioneers who helped found hip-hop (Perry 2004; Chang and DJ Kool Herc 2005). The Caribbean influence on hip-hop also came with the importation of two music trends that emerged in the Caribbean, specifically in Jamaican music, in the 1960s (Hebdige 2004; Perry 2004; Chang and DJ Kool Herc 2005).

First was the introduction of dub music, which consisted of remixing and manipulating sound recordings, often removing the vocals to work with the drumbeats; second was the Jamaican style of toasting, or talking over beats (George 2005; Veal 2007). As Caribbean artists like DJ Kool Herc and Grandmaster Flash integrated into the African American community in the Bronx, they brought their Caribbean influences with them. Out of this fusion came hip-hop music and culture, and a new sound that would soon have a global reach.

Pan-African Dialogues through Music

The musical flows between Africa and the African diaspora are more than a century old. There has been a constant movement of peoples and cultures between Africa and the African diaspora, with cultural styles being adopted, transformed and renamed, and then borrowed again. Tsitsi Jaji (2014), in fact, talks about the “continuities” between African American music and various parts of Africa and the diaspora. Rather than seeing Africa as simply the source of diaspora music and culture, Jaji sees it as part of the cycles of taking, transforming, and giving between connected communities and cultures. Often when we speak of Pan-Africanism it is through the diasporic gaze, through the diaspora reflecting on African connections. We seldom consider the African gaze and African reflections on diasporic linkages. It is crucial to consider both, and in fact to look at Pan-Africanism using multiple lenses, and in consideration of the cultural linkages that encompass a global African (race as opposed to citizenship) population.

According to Edmund John Collins (1987), some of the earliest arrivals of diaspora music in Africa began in the 1880s with the arrival of former enslaved Blacks into West Africa from the United States, the Caribbean, and Latin America. In Ghana and Nigeria, the African American and Caribbean contribution to highlife dates back to the early ...