![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

MANKIND HAS A FASCINATION FOR DISTANT PLACES and different times and a desire to observe such experiences without actually being there.

The paradigm of displays has been to provide a virtual window to a remote scene. In achieving this, the recording and the transmission of images are challenges that are as difficult to master as their presentation. Displays are at the forefront of this visual information link, and their requirements are restricted by the capabilities of our human visual system.

Fortunately, we can use our imaginations to get realistic visual impressions from flat images. We can imagine real scenes even if color is missing, we can approximate depth if the displayed scene is moving, and we can perceive images up to a maximum spatial and temporal resolution.

One of the simplest display implementation requires nothing more than a matrix of dots (also called picture elements, or short pixels) of varying brightness. If these pixels are small enough and dense enough, they will blend into an image for us. If these images are exchanged fast enough, they will merge into a moving scene.

Display technology has evolved tremendously within the past 50 years. The rapid development of semiconductor technology enabled entire circuits to be built directly on glass panels, making many kinds of light-generation principles accessible for display use. New methods of light modulation seem to be discovered every year. The explosive pace of information technology demands the correspondingly rapid development of innovative displays.

If we speak of displays today, we are most likely considering spatial flat panels, but there are many more forms. Projection displays, for example, have made considerable progress; they are so small now that they can be inserted into mobile phones. Microdisplays integrated into glasses may provide an alternative for many existing display concepts, because they can provide the impression of large or small screens without their weight or energy consumption. While some displays provide a fully immersive experience, others have become as flat as paper.

As a result of these developments, the simple “flat” window view that we have been accustomed to for so many years may be relinquished to new display principles providing a truly three-dimensional (3D) experience. These displays may be holographic, they may produce light fields or points in space, or they may simply deceive stereo vision. They may provide images for a singe user or many, and they may provide images dynamically adjusted for the viewer’s perspective or location.

The evolution of displays and accompanying technologies with regard to the recording and transmission of images, has been strongly driven by consumer applications, such as television. Much of it has been enabled by the invention of the raster display, and the basic principle of scanning an image, transmitting it in serial form, and reassembling it at the receiver. In this book we will cover only the display link of this signal chain, with mention of the others where necessary.

The simple serializing principle, for example, may soon be replaced by the transformation of scenes into object descriptions. Presently, this requires a formidable amount of image processing, because object separation may be natural for the human eye but it is still difficult for machines. Yet, it will allow the application of virtual cameras to virtual scenes for synthesizing novel views, as is currently done for computer game scenes. The advantage of this process is a perfect 3D impression for any display size and type. Synthetic and real content can be merged more efficiently, allowing for a wide variety of production maneuvers and visual effects in a very easy way.

Regardless of the recording and transmission chain, displays themselves will be two-dimensional (2D) or 3D in any of the numerous scenarios that are possible today or tomorrow, until –some day– we may bypass the visual system entirely and send images directly to the brain. We will consider the possibilities of brain-computer interfaces in the last chapter of this book, but first we explore the richness of displays, their fundamentals, their applications, and the outlook for this technology.

1.1 DISPLAYS: BIRD’S-EYE VIEW

An electronic display can be considered a converter that translates time sequential electrical signals (analog or digital) into spatially and temporally configured visible light signals (i.e., images). The key component for this conversion is a device that is generally referred to as a spatial light modulator, or SLM.

With respect to the applied SLM technology, displays can be categorized into two main classes: self-luminous displays and light valve displays.

Light-valve displays require additional photon sources (i.e., external light sources) which are modulated spatially and temporally on the basis of either refraction, diffraction, reflection, transmission, polarization or phase changes. Self-luminous displays do not apply external light sources, but generate photons on their own from electrical excitations. A CRT TV is an example of a self-luminous display because it applies an electron beam to excite phosphor to emit visible photons; an LCD monitor is a light-valve display because it filters white back-light sources through polarization changes.

Electronics has always been closely related to display technologies, for signal processing as well as for display driving. From the earliest tube circuits, development has propelled toward highly integrated digital circuits, as well as large-scale semiconductor circuits coated directly onto display panels. An ever-growing number of technologies offer new possibilities. Latest developments, for example, are transparent circuits, organic semiconductors, compounds with carbon nanotubes, or quantum dots. This will be discussed more completely in a later chapter.

1.2 MILESTONES OF DISPLAY TECHNOLOGY

The evolution of display technology has been influenced primarily by the public desire for entertainment, with movie theaters and television being the two drawing cards of the last century, and 3D versions of film becoming increasingly popular at the moment.

Displays have evolved tremendously in the past 250 years, and even 3D became of interest several years ago. Beginning with purely optical experiments, the first real displays were mechanical and electromechanical, then transitioned to electronics, and are now complex digital structures. This evolution was clearly driven by the scientific advances of the corresponding eras. Therefore, it is interesting to consider the major scientific advances that are currently being made in order to hypothesize a potential future continuation of this evolution. Quantum mechanics, for example, will be one of these major scientific advancements.

In searching for the earliest examples of display technology, we first ought to know what we are looking for. The key question is, what is considered display, and what is not. A key property of a display for our purpose is its ability to modulate light into variable images that are not immutable. Thus, we are not looking for static drawings or paintings. We could consider Chinese shadow theaters, but we wish to begin our search with early traces of a technology that changed all of our lives. And here we are: film projection.

1.2.1 Early 1400s to Late 1800s: The Optical Era

Possibly, the very first depiction of a projector was in a drawing by Johannes de Fontana in 1420, showing a candle lantern with a small painted window that projected an image of the devil onto a wall (Figure 1.1(left)). Without a lens, such a projector would be very blurry, and the drawing does not show the details of the lantern very precisely. Therefore, some historians argue that the drawing could also depict a camera obscura rather than a projector. The first notion of lenses is said to date from an Egyptian source in 600 B.C., Archimedes reportedly experimented with lenses (Chrysippos, before 212 B.C.), and spectacles emerged in Europe before 1300 A.D. It is unclear when lenses may actually have been first used in projection systems.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, several people introduced the idea of projecting images, but it was probably not before 1515 that Leonardo Da Vinci presented a drawing of a lantern showing a condensing lens and a candle, unfortunately without giving any hint of actually projecting an image (Figure 1.1(center)).

It is believed that, sometime between 1640 and 1644, Athansius Kirchner showed a device that passed light from a lamp (or sunlight reflected by a mirror) through a painted window that was focused on a wall by a lens. But Kirchner’s first official publication about this device was made in his 1671 book Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae (The Great Art of Light and Shadow), where he called it a magic lantern. In 1659, Christian Huygens presented a similar device, and today it remains fuzzy who the true inventor of the magic lantern really is. The illustration of the magic lantern in Kirchner’s 1671 Ars Magna (Figure 1.1(right)) is also flawed – showing the lens on the wrong side (between lamp and slide). But this might well have been a misunderstanding by the artist who has drawn the sketch, rather than a mistake by Kirchner. The magic lantern concept was used and refined by various individuals, and Thomas Rasmusser Walgenstein, who coined the term Laterna Magica, toured with it through various cities in Europe. One focus of science in the first half of the 19th century was on light, and it was the time when many relevant achievements were made, including public gas light and the first electrical light (years before Edison invented the first practical light bulb). It was also the time when the lighting of the magic lantern was improved.

FIGURE 1.1 Historic drawings of early projectors (from left to right): Fontana’s 1420 projecting lantern without lens (possibly a camera obscura), Da Vinci’s 1515 lantern with lens (but without indication of projecting an image), and Kirchner’s 1640–1671 magic lantern (with lens on wrong side).

The limelight effect –basically an oxyhydrogen flame heating a cylinder of quicklime (calcium oxide), emitting a bright and brilliant light– that was discovered by Goldsworthy Gurney in 1820 was used not only for stage lighting in theaters, but also in the magic lantern. It was replaced by electrical lighting in the late 19th century. The step toward the first digital projectors followed several years later. Several other inventions had to be made before this, and we will return to this subject in later pages.

Clearly, the era of display technology was driven by the possibilities that simple optics offered at that time.

1.2.2 Late 1800s to Early 1900s: The Electromechanical Era

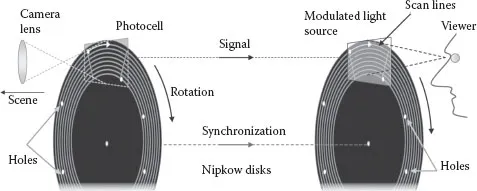

The late 1800s brought not only the evolution of early projectors, but also the first experiments with what became television. Constantin Perskyi coined the term “television” in 1900, and the first devices were mainly electromechanical. In 1884, Paul Gottlieb Nipkow first described his scanning disk, known as the Nipkow disk, Figure 1.2); John Logie Baird demonstrated moving images on it in 1926, and it remained in use until about 1939.

The Nipkow disk is basically a spinning disk with holes at varying lengths from the disk center. For recording, a lens is used to focus the scene on only one segment of the disk. Spinning it causes every hole to slice through an individual line of the projected image, leading to a pattern of bright and dark intensities behind the holes that can be picked up by a sensor (the photoconductivity of selenium had already been discovered by Willoughby Smith in 1873). Conversely, the Nipkow disk can also be used as a display by modulating a light source behind it in synchronization with the recorded light pulses. Thus, the Nipkow disk represents an image rasterizer for recording and display. Since the scan lines are not straight, relatively large disk diameters are required.

FIGURE 1.2 Image recording, transmission and display with Nipkow disks, the very first approach to television.

In the first half of the 20th century, many improvements to the various factors involved in the concept of electromechanical television had been achieved, including recording, signal transmission and display. Note that the first color and stereoscopic variations using additional lenses, disks and filters had been demonstrated by John Logie Baird. But the Nipkow disk would soon be replaced.

1.2.3 Early and mid-1900s: The Electronic Era

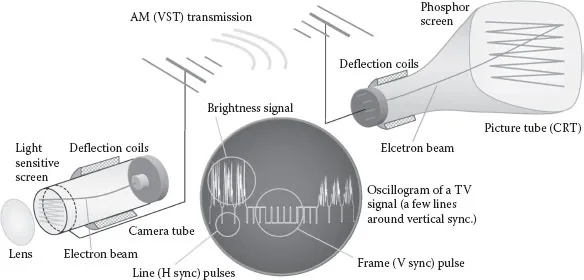

In 1897, Ferdinand Braun invented an initial version of the Braun tube, which is better known as the Cathode Ray Tube (CRT) (see Section 7.6.1 at page 264). Boris Rosing was the first to use the CRT, in 1907, for displaying a received video signal. It became a commercial product in 1922, and soon replaced the Nipkow disk. The CRT revolutionized television and was a major component of the medium until the early 21st century. Like the Nipkow disk, the CRT could be used as a transmitting or receiving device and marked the beginning of the electronic television era. Camera tubes, display tubes and transmission technology continued to improve and were used all over the world. The first fully electronic color picture tube was demonstrated by John Logie Baird in 1944, with early TV standards also evolving in the mid-1900s. For almost half a century, TV technology relied on tube technology and analog signals (Figure 1.3). Broadcasting was done with amplitude modulation (AM), with one side band largely suppressed (vestigial sideband transmission, VST) for better bandwidth utilization. Even with this, only a few of the available radio frequencies could be used at one location, because AM TV transmission is very sensitive to interferences, even from very distant stations. This limited the number of available TV programs, until cable and satellite TV were introduced. Terrestrial TV transmission now has switched to digital in many countries, with an order of magnitude better bandwidth utilization. The CRT not only influenced television, but also improved projector technology. The first CRT projectors enabled the presentation of electronically encoded images to larger audiences. In computer technology, CRT monitors dominated for many decades.

FIGURE 1.3 For half a century, TV technology involved taking pictures with a camera tube, sending them as an analog signal with synchronizing pulses carefully designed to work with simple tube circuits, and finally displaying the images with a c...