eBook - ePub

Apocalyptic Anxiety

Religion, Science, and America's Obsession with the End of the World

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Apocalyptic Anxiety

Religion, Science, and America's Obsession with the End of the World

About this book

Apocalyptic Anxiety traces the sources of American culture's obsession with predicting and preparing for the apocalypse. Author Anthony Aveni explores why Americans take millennial claims seriously, where and how end-of-the-world predictions emerge, how they develop within a broader historical framework, and what we can learn from doomsday predictions of the past.

The book begins with the Millerites, the nineteenth-century religious sect of Pastor William Miller, who used biblical calculations to predict October 22, 1844 as the date for the Second Advent of Christ. Aveni also examines several other religious and philosophical movements that have centered on apocalyptic themes—Christian millennialism, the New Age movement and the Age of Aquarius, and various other nineteenth- and early twentieth-century religious sects, concluding with a focus on the Maya mystery of 2012 and the contemporary prophets who connected the end of the world as we know it with the overturning of the Maya calendar.

Apocalyptic Anxiety places these seemingly never-ending stories of the world's end in the context of American history. This fascinating exploration of the deep historical and cultural roots of America's voracious appetite for apocalypse will appeal to students of American history and the histories of religion and science, as well as lay readers interested in American culture and doomsday prophecies.

The book begins with the Millerites, the nineteenth-century religious sect of Pastor William Miller, who used biblical calculations to predict October 22, 1844 as the date for the Second Advent of Christ. Aveni also examines several other religious and philosophical movements that have centered on apocalyptic themes—Christian millennialism, the New Age movement and the Age of Aquarius, and various other nineteenth- and early twentieth-century religious sects, concluding with a focus on the Maya mystery of 2012 and the contemporary prophets who connected the end of the world as we know it with the overturning of the Maya calendar.

Apocalyptic Anxiety places these seemingly never-ending stories of the world's end in the context of American history. This fascinating exploration of the deep historical and cultural roots of America's voracious appetite for apocalypse will appeal to students of American history and the histories of religion and science, as well as lay readers interested in American culture and doomsday prophecies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Apocalyptic Anxiety by Anthony Aveni in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia de Norteamérica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Episode 1

October 22, 1844

1

Millerites and the Biblical End of the World

A man with a conviction is a hard man to change. Tell him you disagree and he turns away. Show him facts or figures and he questions your sources. Appeal to logic and he fails to see your point.

—Psychologist Leon Festinger

It began in the “Burned-over District,” a funnel-shaped conduit of turf between New York’s Adirondack and Catskill Mountains that opens into the Great Lakes and connects the Midwest to New England and colonial America’s eastern coastal cities. Early in the nineteenth century, during a period of intense religious revivalism known as the Second Great Awakening, religious dissenters, along with adventurers and opportunists, trekked their way out of the established territory of the Northeast toward the open frontier via the newly constructed Erie Canal.1 The fervor of unorthodox Yankee social and religious practices that swept over the area like fire in a dry cornfield would bestow the char on the territorial label this region would come to acquire. Here Adventism, a belief in the imminent Second Coming of Christ, would become the birth child of Pastor William Miller (figure 1.1).

Miller was born at the end of the American Revolutionary War in 1782. Typical of the New England “Yorkers,” his pioneer family, like that of Mormon founder Joseph Smith, had migrated across the wilderness line from settled communities in western New England. By modern standards, you could call the Miller family middle class. William’s frugal parents held a mortgage on a small farm in upstate Yates County, New York. The Millers were well read, politically involved, and deeply religious—the mother pious, the father descended from a long line of preachers.

Figure 1.1. Pastor William Miller, leader of a religious fringe group that would become the Seventh-day Adventist movement, preaches to a popular audience. (© Review & Herald Publishing / GoodSalt.com.)

Young William was bookish and he kept a diary. An early entry reads: “I was early educated and taught to pray the lord.”2 He was fifteen at the time. Miller later married, served a stint in the militia, then fought in the War of 1812. Once discharged, he worked his way up in county government, became established financially, and settled into the life of a gentleman farmer. It is worth noting that before he became an interpreter of biblical passages, Miller was a deist, one who believes that, though a supreme being created the world, reason and the observation of nature alone can be used to determine the relationship between people and God. Skeptical of ideas tied to his Baptist upbringing, Miller became immersed in his own study of the Scriptures. He also developed into a devout apostle of apocalyptic eschatology, the belief that God has disclosed, in the Scriptures and other forms of revelation, secret knowledge of a particular kind about the end of the world—the “mysteries of heaven and earth.” Young Miller managed to convince himself not only that the word of the Bible was absolutely pure revelation, but also that its prophetic messages pointed to an imminent event of world-shaking proportions. Far from appearing a religious fanatic, Miller was characterized by his contemporaries not so much as an inspired prophet but rather as a humble logician driven to conduct patient research, a man with a resourceful and imaginative mind and a literal-minded soul.3

His principal early biographer, the Adventist historian Francis Nichol, traces Miller’s first specification of a date for the end of the world as we know it back to 1818, when he recorded in his diary that in about twenty-five years “our present state would be wound up.”4 Four years later Miller wrote out his detailed justification for timing the event as well as the method for arriving at it, though initially he refused to go public.

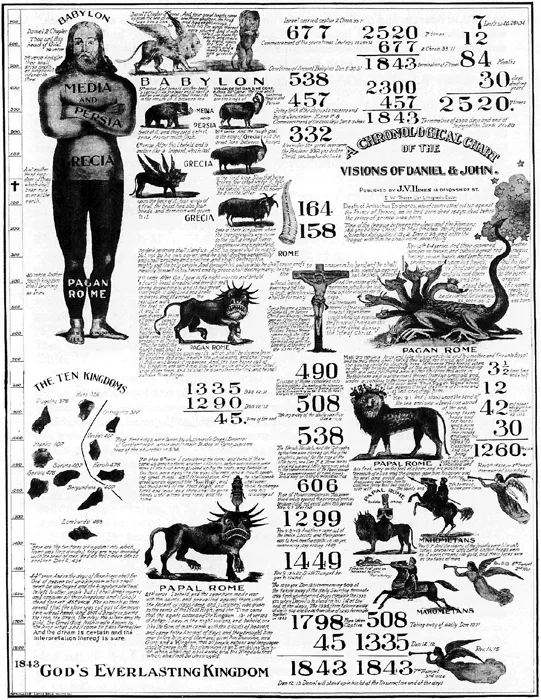

Figure 1.2. Pastor Miller used this chart (an enlargement of that shown in the background of figure 1.1) in his lectures to sketch out the biblical mathematics that portended the end of the world, which he predicted would come in 1843—later revised to 1844. (P. G. Damsteegt, Foundations of the Seventh-day Adventist Message and Mission [Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1977], 310.)

Precisely what biblical passages pointed to a premillennial Advent circa 1843? Miller displays his number-crunching logic in a famous numerological chart frequently used to illustrate his lectures (figure 1.2). He based his argument on prophecies in the Old Testament book of Daniel and in New Testament Revelation, together with the long-held key assumption that numbers specified in Scripture as days are to be interpreted instead as years; for example, Numbers 14:34 tells us: “According to the number of the days . . . each day you shall bear your guilt, namely forty years.” Miller started with the decree of Artaxerxes, given in the seventh year of his reign, to rebuild Jerusalem, written in Daniel 8:14: “For two thousand and three hundred evenings and mornings; then shall the sanctuary be restored to its rightful state.” He took this to mean that 2,300 years after 457 BCE, the date he assigned to the commandment issued to the prophet Daniel by the angel Gabriel, the sanctuary will be cleansed of all sin by the Second Coming of Christ.

What else could the sanctuary be but the church? reasoned Miller. And surely the cleansing must refer to total redemption from sin in the aftermath of Christ’s Second Coming. A second passage, also from Daniel (9:24–27), reads: “Seventy weeks are determined upon thy people . . . to make reconciliation for iniquity, and to bring in everlasting righteousness, and to seal up the vision and prophecy, and to anoint the most holy.” Miller thought this prophesied that seventy weeks, or 490 days—equal to 490 years—were already cut off from the first part of the long period in Daniel 8:14. So the math is simple: 2,300 ‒ 457 = 1843 CE.

But, notes historian Ruth Alden Doan, Miller didn’t stop there.5 Dedicated to the principle that no portion of Scripture involving number coincidence should be overlooked, he interpreted the number 1,335 (Daniel 12:12) to be the number of days (again, years) between the establishment of papal supremacy (he sets that at 508 CE) and end-time: 508 + 1,335 = 1843 (see the bottom of the chart in figure 1.2). Later Miller reset the first date at 538 CE, added it to the 1,260 days (years) of the woman in the wilderness mentioned in Revelation 12:14, and landed on 1798, the date the papacy fell to Napoleon. In this case the last days made up the 45 years between 1798 and 1843. By subtracting the 70 weeks in Daniel (490 years) from 2,300 years and tacking on the 33-year life of Christ, the pastor again arrived at 1843—another coincidence.

What would happen? How would it end? To address these questions Miller turned to the New Testament’s last chapter, the Revelation according to John. Revelation 6:13–17 paints a frightening portent:

And the stars of heaven fell unto the earth, even as a fig tree casteth her untimely figs, when she is shaken of a mighty wind.

And the heaven departed as a scroll when it is rolled together; and her mountain and island were moved out of their places.

And the kinds of the earth, and the great men, and the rich men, and the chief captains, and the mighty men, and every bondman, and every free man, hid themselves in the dens and in the rocks of the mountains;

And said to the mountains and rocks, Fall on us, and hide us from the face of him that sitteth on the throne, and from the wrath of the Lamb:

For the great day of his wrath is come; and who shall be able to stand?

Armageddon will be the place where God’s and Satan’s army will confront one another at the end of the world. All sin and sinners will perish and a New Jerusalem will rule for eternity.

Interestingly, some of Miller’s detractors foresaw not the physical catastrophic conflagration—the doom of fiery judgment cast upon sinners—but rather the more blissful Advent of a moral regeneration for those who would redeem themselves. Rule by physical force and demonstration of power is surely not God’s way, they reasoned. It sounded, as historian Michael Barkun characterizes it, too much like “a sad last resort inadequate for a God capable of triumph through nobler means.”6

Some viewed the Advent as gradual rather than sudden—the coming of an age of God’s mercy. But everyone, theologian and prophet alike, agreed: something big—or at least the beginning of it—lay just over the horizon; biblical prophecies, however interpreted, were on the verge of being fulfilled.

If the end was near, then the world would need to know it—and Miller would be the one to tell it. And so in 1831 he made himself over from farmer to preacher, moving from pew to pulpit. Once the harvest was in Miller would mount the dais wherever and whenever he had the opportunity. “There was nothing halfway about Miller. He reminds one a little of the Apostle Paul,” Francis Nichol describes him. “He thought and acted intensely. He used in abundance those hand maidens of the fervid—colorful adjectives and superlatives.”7 However, Michael Barkun’s less biased, more recent assessment tells us that Miller did not attract followers because of his oratorical skills. He pictures Miller as a rather bland individual who, though sincere in his personal commitment, was a colorless figure “utterly lacking in glamour and magnetism.”8 Barkun attributes Miller’s efficacy to his persistence at a time when his message seemed appetizing to those in the communities where he preached.

Miller’s sphere of influence quickly began to expand well beyond remote rural towns as he acquired a band of followers from adjacent Massachusetts and even more distant Connecticut. The messenger became as important as the message. In 1835 he wrote to one disciple, the Reverend Truman Hendryx, “I now have four or five ministers to hear me in every place I lecture. I tell you it is making no small stir in these regions.”9 The media fueled his fire: in 1832 a Vermont newspaper spread the word by publishing Miller’s lectures. Evidently the preacher himself shared what he interpreted to be his audience’s high opinion of his skills as a persuasive speaker. As Miller’s diary reports: “As soon as I commenced speaking . . . I felt impressed only with the greatness of the subject, which, by the providence of God, I was enabled to present.”10

Aggressive promotion by the organization that grew around Miller also had a profound effect on the movement’s success. Pamphlets detailing the pastor’s sermons published in lots of a thousand or more quickly sold out. His diary informs us that between October 1, 1834, and June 9, 1839, Miller delivered 800 lectures, some with as many as 1,800 in attendance, on the “Advent near” theme. In a span of eight weeks in 1836 he gave a total of 82 lectures, sold $300 worth of pamphlets, and received an undisclosed number of small financial donations. By his own estimate Miller pre...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: December 21, 2012—It Didn’t Happen

- Part I: Episode 1, October 22, 1844

- Part II: American Apocalypse

- Part III: New Age Religion and Science

- Part IV: Episode 2, December 21, 2012

- Conclusion: Contrasting the Signs of the Times

- Notes

- About the Author

- Index