![]()

1

An Extraordinary Opportunity to Be Denounced as a Wit: How Magazines Launched “Dada,” 1916–1917

In 1920, German Dadaist Richard Huelsenbeck recalled,

Tristan Tzara was devoured by ambition to move in international artistic circles as an equal or even a “leader.” He was all ambition and restlessness … And what an extraordinary, never-to-be-repeated opportunity now arose to found an artistic movement and play the part of a literary mime! … What a source of satisfaction it is to be denounced as a wit in a few cafés in Paris, Berlin, Rome!1

Intended to insult, Huelsenbeck’s words capture Romanian poet Tristan Tzara’s drive to launch an art movement in the midst of war. In 1916, when the First World War had been underway for almost two years, a small cluster not involved in the fighting—including Huelsenbeck, Tzara, Emmy Hennings, Hugo Ball, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, and Marcel Janco—congregated in neutral Zurich and put on performances at a café they called the “Cabaret Voltaire.”2 In 1916 and 1917, these figures, soon known as the Dadaists, also issued magazines, starting with Cabaret Voltaire, followed by Dada. These publications were their tickets into avant-garde circles in other cities despite travel and exhibition restrictions. They also enabled those involved to forge and propagate Dada even as the rampant nationalism around them exposed the dangers of forming a collective identity. But at the same time, the journals enabled their makers to mock the very idea of unifying around any single doctrine and to frustrate attempts to pin down what “Dada” stood for. Cabaret Voltaire and Dada 1 and 2 served as much more than records or purveyors of events, writings, and artworks. Indeed, at first, they were all these individuals really had. The magazines made it so that their makers could pretend they were more than they were, as it were, and “play the part,” to borrow from Huelsenbeck, while refusing to explain what they stood for and, in fact, offering “nothing.” In a way, they were the manifestation of Huelsenbeck’s “Erklärung” (“Declaration”), presented in spring 1916 at the Cabaret Voltaire, which simultaneously sets up expectations and dashes hopes for a clarification: “We want to change the world with Nothing, we want to change poetry and painting with Nothing, and we want to end the war with Nothing.”3 Despite and because the Zurich collective had relatively little to publicize, they made magazines.

This chapter begins by explicating Cabaret Voltaire’s dual identity as a cabaret-like anthology and as a periodical. German writer and dramaturg Hugo Ball originally conceived Cabaret Voltaire (June 1916, Zurich) as a means of broadcasting events and artistic styles and brazenly championing transnationalism with a cabaret-like eclecticism and dynamism.4 Tzara, on the other hand, framed Cabaret Voltaire as a distinct yet related medium, a magazine. Regardless of intent, in both guises, it advertised Tzara’s subsequent magazine, Dada, and “Dada,” even amid conflicting attitudes about their future.5 After introducing Tzara’s Dada, the chapter moves on to analyze how Tzara, Cabaret Voltaire, Dada, as well as avant-garde journals in European cities and New York promoted “Dada” without explaining it, ultimately spurring multiple interpretations.

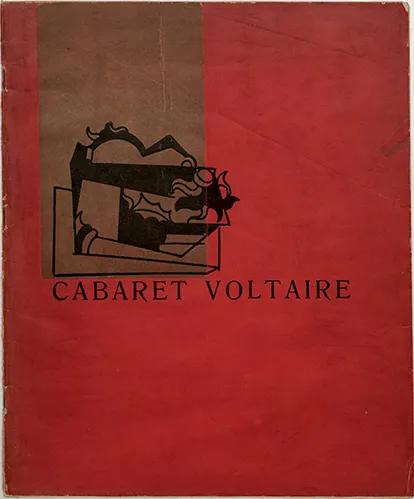

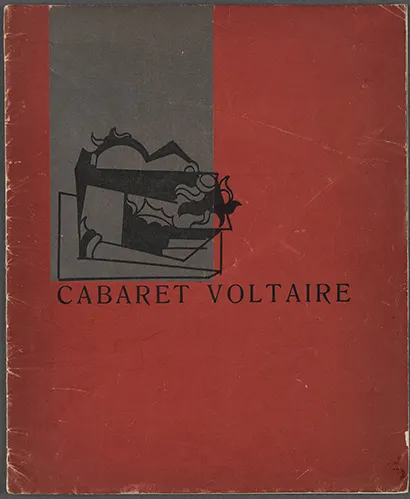

Cabaret Voltaire: From Anthology to Magazine

Thirty-two pages long with five hundred copies printed (by anarchist Julius Heuberger), Cabaret Voltaire was an ambitious undertaking on Ball’s part.6 In a June 1916 diary entry, he boasts that Cabaret Voltaire is “the first synthesis of the modern schools of art and literature.”7 Cabaret Voltaire echoes the variety of performances and the broad range of works adorning the Cabaret’s walls: paintings, collages, drawings, poems, and reproductions by local and distant artists representing Cubism, Expressionism, and Futurism.8 Among the contributions from outside of Zurich, poems by Wasilly Kandinsky and Jakob (here “Jacob”) van Hoddis exemplify Expressionism, poems by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and Franceso Cangiullo speak for Futurism, and an untitled etching by Pablo Picasso, likely published without his permission, across from Guillaume Apollinaire’s poem, “Arbre,” illustrates Cubism (though a letter from Italian artist and editor Enrico Prampolini to Tzara from March 17, 1917, suggests that Picasso was not consulted).9 Alongside these pieces, Ball showed contributions by his comrades at the Cabaret, many of which reveal their indebtedness to these artists. On its striking cover, a thick strip of gold or silver foil (depending on the copy) is affixed to a deep red background, overlaid by the title and an abstract woodblock print by Arp in black ink (Figures 1.1 and 1.2).10 Inside, a sketch by Max Oppenheimer, Arp’s and Otto Van Rees’s collages, and a tapestry by Arp and Sophie Taeuber-Arp recall Cubist collages and Expressionist paintings. Marcel Slodki’s woodcut is Expressionist-inspired, while Janco’s drawing for a poster for the “Chant Nègre” (literally, “Negro Song”) (which took place on March 31, 1916) is informed by both Cubism and Expressionism. Literary contributions include texts by Ball, Hennings, and Huelsenbeck.11 In part to avoid censorship, Ball produced a German and a French version of his magazine. They are identical except for the title page and his introductory essay, originally composed in German. But both include a mix of German, French, and Italian, reinforcing Ball’s transnational goals.

Cabaret Voltaire captures not only the notable pluralism and dynamism of the Cabaret Voltaire, but of cabarets in general, which Ball knew well.12 In early twentieth-century popular culture, “cabaret” denoted a playful, intimate, popular, if usually underground art form featuring a variety of acts. The emerging Dadaists’ performances also invoked the German iteration of the “Kabarett,” which was literary and artistic with a distinctive taste for parody and dark humor.13

Figure 1.1 Cabaret Voltaire, ed. Hugo Ball, Zurich, 1916, Meierei Verlag, front cover, 10 5∕8 × 8 11∕16 in. (27 × 22 cm). Spencer Collection, New York Public Library (see Plate 1).

Figure 1.2 Cabaret Voltaire, ed. Hugo Ball, Zurich, 1916, Meierei Verlag, front cover, 10 5∕8 × 8 11∕16 in. (27 × 22 cm). International Dada Archive, Special Collections, University of Iowa Libraries (see Plate 2).

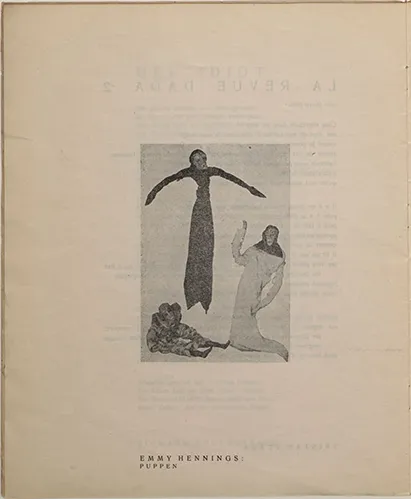

Eclectic and provocative, Cabaret Voltaire functioned not simply as an anthology traditionally conceived, but also, with its assortment and sequencing of materials, as a lively compilation akin to a cabaret. Ball’s opening essay for Cabaret Voltaire, which begins, “When I first set up the Cabaret Voltaire,” reads like a cabaret impresario’s opening to a show. It tells the story of how he went about instituting the cabaret and attracting press coverage and announces the characters within the publication and their submissions: “And, at Mr. Tristan Tzara’s instigation, Mssrs Tzara, Huelsenbeck and Janco performed […] a simultaneous poem of his own composition.”14 What follows is a mishmash of many distinct kinds of contributions, each of which brings with it a distinct mode of address and a set of references and conventions.15 The poem “L’Amiral cherche une maison à louer” (“The admiral is looking for a house to rent”) resembles a musical score and a photograph of Hennings’s puppets that calls to mind puppet-theater plays (Figure 1.3). The text “Dada: Dialogue entre un cocher et un alouette” (“Dada: Dialogue between a coachman and a swallow”), a skit between Huelsenbeck and Tzara, reads in part like an advertisement (“the first number of the Dada Review comes out on August 1, 1916. Cost: 1 fr”), succeeded by a poster image and reproductions of artworks.16 The publication thus brings together music, theater, crafts, advertising, and fine art, each eliciting a different response from readers. Combined, they create a disjointed effect.

Figure 1.3 Cabaret Voltaire, ed. Hugo Ball, Zurich, 1916, Meierei Verlag, p. 20, 10 5∕8 × 8 11∕16 in. (27 × 22 cm). International Dada Archive, Special Collections, University of Iowa Libraries.

Such dynamism in Ball’s publication usually goes unnoticed. Accounts typically prioritize the stage over the page, valuing it as a source of images and writings, a record of Dada events, and demoting its reproductions to mere “reminders,” “relics of actions,” and “incomplete documentation.”17 In his famous book, Lipstick Traces, for example, Greil Marcus compares the Zurich Dada events and Cabaret Voltaire, concluding, “Whatever happened in Zurich in the spring of 1916 […] it wasn’t in the archives.”18 Yet the cabaret-like heterogeneity of Cabaret Voltaire renders it interactive, demanding that readers shift approaches with each type of text or image they encounter.

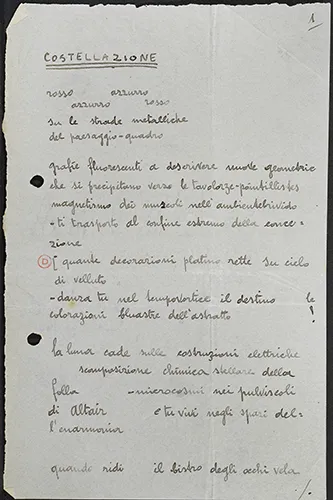

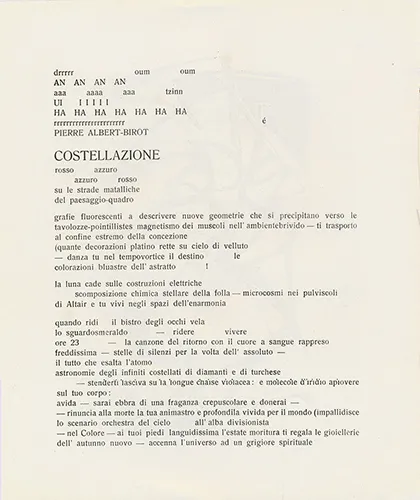

Cabaret Voltaire’s graphic design is rather restrained compared to later Dada publications. The irregular spacing in Gino Cantarelli’s poem, “Costellazione,” in Dada 2, is among the more daring elements, the result of Tzara’s and Heuberger’s attempts to reproduce the poem according to Cantarelli’s mock-up, in which some lines begin far to the right of the page, and random elements, like the exclamation point, float in space (Figures 1.4 and 1.5).19 In Cabaret Voltaire images are in shades of black and gray on glossy stock paper and take up an entire page. For the most part, texts and images appear separately from one another and the font type and size change hardly at all throughout the issue. The staid typography and layout, however, actually heighten the absurdity of the publication’s content. For instance, the lines from Tzara’s poem, “La revue Dada 2”—“there is a young man who is eating his lungs / then has diarrhoea [sic] / then lets out a luminous fart”—appear in soberly arranged serif typeface.20 Content and formatting conspire to prevent the reader from perusing passively and relying on visual cues, evoking the deadpan humor characteristic of Dada performances.

Figure 1.4 Gino Cantarelli, “Costellazione,” manuscript/mock-up of poem published in Dada 2, 1917, 2 pages. 8 ¾ × 14 1∕3 in. (22.3 × 14.3 cm), p. 1 of 2. Dossiers Tristan Tzara, Bibliothèque Littéraire Jacques Doucet, Paris, Photo by Suzanne Nagy.

Figure 1.5 Dada 2, ed. Tristan Tzara, Zurich, 1917, p. 8, 14 × 9 in. (29 × 23 cm). International Dada Archive, Special Collections, University of Iowa Libraries.

Cabaret Voltaire played a primary role in relation to Spiegelgasse 1 in another way, too: it likely gave the space its name. Ball and his cohorts did not call the...