eBook - ePub

Adoptive Youth Ministry (Youth, Family, and Culture)

Integrating Emerging Generations into the Family of Faith

- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Adoptive Youth Ministry (Youth, Family, and Culture)

Integrating Emerging Generations into the Family of Faith

About this book

Kids desperately need healthy, committed adults who can help them thrive in their faith and become active participants in the life of the church. This requires the efforts of the whole faith community. Chap Clark, one of the leading voices in youth ministry today, brings together twenty-four experts from a variety of denominations and traditions to offer a comprehensive introduction to adoptive youth ministry, a theologically driven, academically grounded, and practical youth ministry model. The book shows readers how to integrate emerging generations into the family of faith, helping young adults become active participants in God's redemptive community.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Adoptive Youth Ministry (Youth, Family, and Culture) by Clark, Chap, Chap Clark in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Ministry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1: The Context of Adoptive Youth Ministry

Consider this unsolicited email from an eighth-grade boy to his youth pastor about the multigenerational mission event that people from his church were going to attend.

“One of my biggest reasons of why I want to go is to worship God in that huge mass amount of people! If I think church camp is amazing then this has to crazy awesome, and I think it’s great! Not only we get to have fun and worship but we get to have a work experience too! I can’t wait to meet people and find new siblings!”

There’s no easy way to say this: The American evangelical church has lost, is losing and will almost certainly continue to lose our youth. For all the talk of “our greatest resource,” “our treasure,” and the multi-million dollar Dave and Buster’s/Starbucks knockoffs we build and fill with black walls and wailing rock bands . . . the church has failed them. Miserably.

—Marc Yoder, “10 Surprising Reasons Our Kids Leave Church”1

Adoptive ministry is the biblical calling describing our role in recognizing and participating in God’s declaration that in Christ we have been called “children of God” (John 1:12). As churches attempt to build community among those who gather together as God’s people, adoption is the term used as the biblical foundation for drawing disparate people into the family-like intimacy we have been invited to in Christ. Adoptive youth ministry, then, provides the biblical foundation for the inclusion of young people into the core of the Christian community.

When I first began using the term adoption to describe how we are called see ourselves as connected siblings of one another in the church—and therefore how we envision ministry to the body and beyond—not everyone immediately jumped on board. Essentially, those who struggled landed in two basic camps.

First, some people believe the term is confusing because it is most commonly used for families adopting children into their home. Clearly the word is embedded within a very specific context. Wouldn’t it confuse people to use the term in a different, albeit broader, way? This is actually a strength of its use. For this very reason, Paul chose this term to break down the walls dividing the early church. Using adoption to describe what it means to live together in God’s family concisely raises the bar of the relational connectedness and intimacy we are called to in Christ. People already know that to adopt a child changes everything—not only for the child but also for the receiving family. By using this familial language, this same intentionality is applied to who we are and how we function in the community of faith, thereby capitalizing on the term’s familiarity. In using adoption we are more readily able to embrace the complexity, the messiness, and the emotional energy that comes with taking in a child who, by nature of the choice the family makes, is endowed with all the rights and privileges of a biological child. Those I have talked with who have adopted children or are adopted themselves have overwhelmingly resonated with the concept of adoption as a grounding theological base for youth ministry, and every ministry.

The second objection involves the implicit implication such a label will have on the term intergenerational, which is currently in vogue. As many churches have come to recognize fragmentation in the church and how it creates multiple communities within a single congregation, they have instituted programs and strategies to connect people of various groups and ages. Some who have embraced the concept of “intergenerational ministry” wonder whether adoption is too top-down a word. However, this assumes that intergenerationalism levels the playing field of communal engagement and that as young people and older people are given the opportunity to know one another they will be drawn to one another as equals, or at least co-participants. Last year at a summit of youth ministry writers and leaders, I was given a few minutes to pitch the idea of adoptive ministry. One participant remarked, “I don’t think ‘adoption’ is an especially helpful metaphor for youth ministry. It is hierarchical and devalues kids.” This comment and the resultant conversation forced me to think more deeply about what I mean by adoptive ministry. Any ministry concept that devalues young people is clearly not what is appropriate in the desire to integrate young people into the life of the church community. As mentioned in the introduction, adoptive ministry is not about adults “adopting” the children or adolescents of a church as their own. Rather, because God is the one who adopts all of us, adoptive ministry is more directly communal and inclusive, more straightforward and therefore easily explainable, and far more radical than any previous foundational theology of youth ministry practice.

Participating in what God declares as truth is the reality of who we are together as his children. In the course of teaching, writing, and speaking about this subject in various contexts, this discussion has not only caused me to describe more carefully the implications of adoptive ministry but has also given me greater confidence that adoption is the most helpful and direct biblical metaphor for the church in today’s atomized society. Since it has been declared by God that we are siblings of one another, we are members of the same household and family, and we hold the same standing before the God who has called us. Nothing could be less hierarchical.

Adoptive ministry, however, is less about fostering diverse relationships and more about changing our fundamental mind-set of how we relate to one another in the church. It is first and foremost about attitudinal change; structural change will follow. The shift from where we are to where we need to be is significant, but in today’s culture of disinterest and disdain we are losing both kids and relevancy; we simply have no choice. We must move from the historical complacency of institutional and programmatic defensiveness into the uncharted, mysterious, and uncontrollable waters of abandoned life together in Christ. This is what adoptive ministry means.

Adoptive Ministry

The Move from Institution to Organism

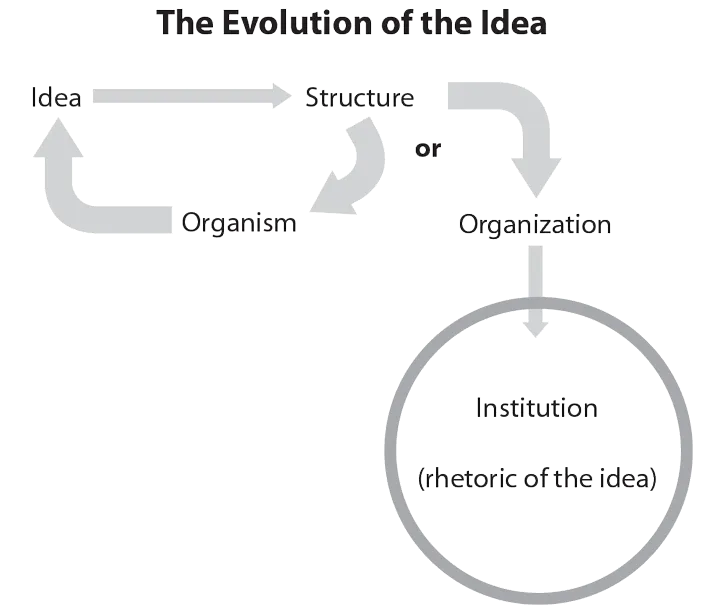

Several years ago, while trying to integrate various perspectives on organizational dynamics and group leadership, it occurred to me that anything of merit begins with an idea (e.g., “we need more efficient transportation”). With any idea that matters, we must create a structure that promotes the idea in a specific context (a contextual application of the idea, as in “we need a car with four wheels and rubber tires”). As we refine the application, we almost always begin to see the structure as being essentially one with the idea, and we end up protecting and controlling the structure that promotes the idea (e.g., “Consider a car; how many wheels does it have? Of course. Four.”).2 Yet to keep an idea alive in a changing environment, the temptation to control or contain how it is applied and constantly seek to restructure the essence of the idea must be resisted. (“Why not five wheels, on plastic tires?”) To maintain the integrity of an idea in any fluid climate means we must be willing to change how we envision the idea in different settings and contexts. What matters, then, is the idea, not how it is structured or applied.

I have come to see all change in these terms. Ronald A. Heifetz and Marty Linsky remind that “people do not resist change, per se. People resist loss.”3 There is such great power in maintaining what we know and what we have become comfortable with that anytime a “fixed” idea is challenged—even by simply asking a question or proposing a new way of thinking—our default response is to become nervous. We wonder what will happen if what we have believed in and relied on is lost. Yet this must happen in order to change how youth ministry has been practiced for decades. We must move from running a program to being a family—from functioning as an institution to living as an organism.

The Evolution of the Idea

For an idea to go anywhere, it must have some sort of structure to give it legs. Once a rudimentary structure is in place, especially in its early iterations, the structure may go through fits and starts; yet if the idea has merit, eventually the structure enables the idea to gain momentum. At this stage, whoever owns the idea is forced to choose. Most typically, the choice is made to commit to and therefore formalize the structure by creating an organization with layers, hierarchy, tenets, and procedures in the attempt to ensure that the idea continues in its current iteration. Once this happens, however, the idea becomes subject to the power of the organization itself and has only one trajectory—to become so codified and rigid that it becomes an institution. In this use of the term, an institution is an organization that is in the business of perpetuating itself by using the power of the organization to keep it going and the rhetoric of the idea to give it perpetual legitimacy. Once this occurs, the idea is no longer what drives practices and structure because the institution is now in control. Depending on the power of the institution and how deeply the leaders cling to it, changing or even questioning the assumptions, tenets, and reasoning of the institution is extremely difficult. It becomes, in essence, a closed system in which outside forces and voices are perceived as threats to the integrity of the institution’s reason for being. The idea is considered to be alive, but the idea has been strangled by the power of the institution. If not dead, the idea is buried so deeply it is only a matter of time before the institution becomes an empty shell devoid of meaning.

In my experience, this process is inevitable without dedicated and deliberate leadership. As an example, take the idea of socializing the young in a society. The child needs to be taught not only concepts but also history and values and must be given the opportunity to observe these in action. So a society may choose to gather the children together in order to pass on the story so that the children will be ready to enter the greater community as peers when the time is right (this signifies the structure, the contextual application of an idea). Over time, as curriculum is developed and teachers are trained, the structure gains traction and soon becomes an organization. But unless the caretakers of the idea fight to keep the idea at the center, the organization will become so formalized, with layers of hierarchy and tenets that maintain the status quo, that it will morph into an institution that retains the idealized rhetoric to “socialize the young” but is now so powerful and solidified that it has become an idea unto itself.

What, then, is the antidote to institutionalism? How can an idea be maintained with integrity, even in changing environments? At the point where the idea begins to take shape as a structure, the crucial decision needs to be made by those who control the idea: either we commit to our structure—what we have learned, how we think about what the idea means in a given context—and evolve into an organization that eventually slips into an institutional morass, or we continually campaign on behalf of the idea and become an organism, an open system that seeks out any and all input in order to keep the idea alive. The choice is always the same: commit to the messy, unknowing life of a living entity by being willing to experiment with new structures and pursue any questions that would cause the idea to thrive, or settle for a fixed (and proven?) structure that may appear healthy but in the end will ultimately self-destruct the idea. Interestingly, the two most common uses of the term institution (besides marriage) are education and the church, both of which are hugely powerful institutions with long histories, time-honed practices, and sacred assumptions that only the most “out there” are willing to attempt to improve.

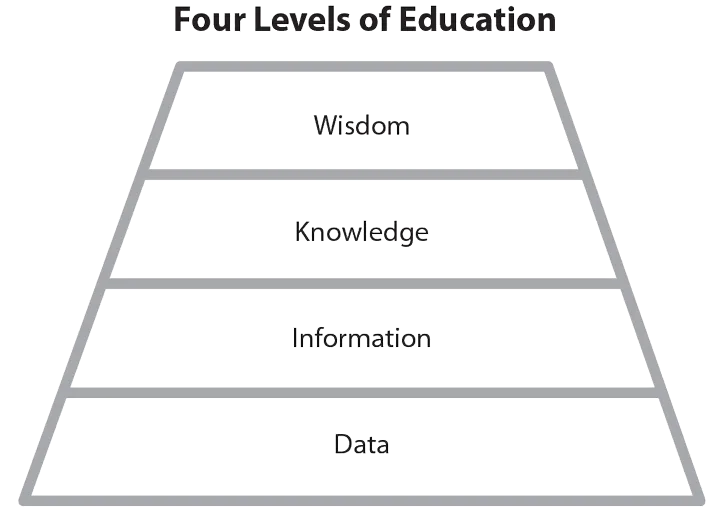

Let’s return to the education example mentioned above. With all of the data available on how growing up is changing—how boys and girls develop differently and the way in which the brain matures—should the way contemporary education is delivered be reconsidered? Are we willing to go back to the original idea, that is, to develop mature, healthy adults who will take what has been given them and move the story forward? Can we ask questions like why middle school? What if schools were made smaller? What if boys and girls were educated separately? Why five days a week? Don’t ask. The goals of education have become so limited for most kids that the surface of socialization is barely scratched as educational institutions seek to develop “competencies” in order to stay “competitive” with other societies. Education is now about data (raw content) and information (integrating data into categories). Socialization and the making of healthy, interdependent adults begins with data and information. Young people need help to move beyond mere content into knowledge (connecting the dots created by data and information into a cohesive landscape where true interdependent interaction and deliberation can take place), with the ultimate goal of producing men and women who embody wisdom—who can use knowledge to contribute to the greater good.

Now, what about the church? How do we “do” church? How is staff hired? How is the church going to be structured? Most important, what is the strategic goal for ministry?

For the church to become a family—which, in terms of health, means our life together needs to be experienced as an open system, or essentially as an organism—we must be open to thinking differently about how to operate as a community. We must be strategic and holistic, but we also must be willing to ask any and every question that would keep us from living into who we are called to be. After all, the first church (Acts 2) did not have a preordained plan or organizational structure in place. All that is known is that those in the early church quickly bonded to one another, and the family grew: “All the believers were one in heart and mind. No one claimed that any of their possessions was their own, but they shared everything they had. . . . More and more men and women believed in the Lord and were added to their number” (Acts 4:32; 5:14).

Even within the time frame that the New Testament was written, over time the structure of the local chu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Endorsements

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Contributors

- Introduction

- Part 1: The Context of Adoptive Youth Ministry

- Part 2: The Call of Adoptive Youth Ministry

- Part 3: The Practice of Adoptive Youth Ministry

- Part 4: The Skills for Adoptive Youth Ministry

- Notes

- Scripture Index

- Subject Index

- Back Ads

- Back Cover