![]()

1

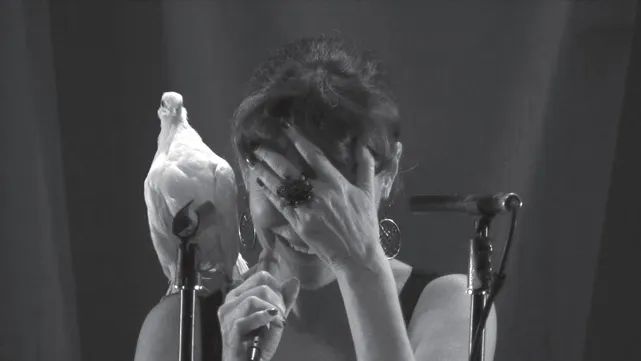

Lupe at the Mic

After January 1959, Havana, Cuba, in Tatlin’s Whisper #6

There was the usual milling around, on the basis of sketchy information. A stage was set up in the patio of a cultural center in the old part of the city—the restored, charming part full of restaurants and shops, the part where power blackouts and water shortages are rare and where crime is minimal because of all the police. Strong lights hit a podium on the stage in the darkening patio; a huge golden curtain hung behind it. A phalanx of big TV cameras, national and international press amid the noisy crowd—by now hundreds of people.

The crowd is pretty mixed. Since the performance is part of the Havana biennial, pretty much all the foreigners are somehow connected to the arts (collectors, curators, artists, etc.), but the Cubans come from a broader slice of the population. After a long while there’s a little flurry of excitement: A cardboard box of something is brought out, and an announcement is made about people taking something from it. The box is filled with several hundred disposable cameras, and people push over to grab them, passing them along from hand to hand. The space has gotten even more crowded and noisy and expectant.

I don’t remember exactly how it started, but someone must have explained that anyone was welcome to take the stage and speak into the microphone for a minute. Maybe they had been there before, but it was then that I noticed a couple of kids in army fatigues holding a dove. After not too long things got going, and in a ragged and stop-start kind of way people went up and spoke: some of them shouting; a few fists raised in the air; some cries and cheers from the crowd; some confusion about what had been said, since the sound quality was bad; some defiance; some awkward declarations; some dead air; some confessions (“I’ve never felt more free”; “I am afraid”). Each time, the dove was put on the speaker’s shoulder.1 Usually it flapped around in the speaker’s hair or flew off; each time, the guards would catch it and put it back. The performance had started late but ended punctually after exactly an hour, when the artist, the last to speak, said, “Thanks to the Cubans.”

I was standing with a few friends, and over the course of the hour our disagreement about what was happening got stronger, to the point that one of us was furious, one exhilarated, and the other two of us deeply conflicted (of course). The performance was aimed at both romantics and cynics, and it had caught each of us at that edge.

What Happened (First Pass)

Right at the beginning a woman takes the mic and starts to cry. It takes most of the minute she’s up there for people to quiet down, and even then there’s still a lot of hubbub. She leaves without saying a word, still shaking with sobs. Some people recognize her because she had been an important teacher and mentor until she left the country years ago, along with a lot of others.

Yoani Sánchez is next. She goes up right after Lupe leaves, and the shift in tone is almost violent: There’s no interval for the emotion to settle. Now it’s a protest rally, and the atmosphere is emphatic. Yoani reads a short speech: “Cuba is an island surrounded by the sea, and it is also an island surrounded by censorship,” she begins. “Some cracks are opening in the wall of control…. We are still only a few bloggers, our sites highlight the awakening of public opinion.” The sound system is not great, and there’s a lot of reverb, which not only makes it hard to understand but also creates the sense of being in a giant space, an arena instead of a relatively intimate patio. That discrepancy piles onto the latent one—the sense of things just generally being askew, not adding up right. What does register succinctly is that this is a big deal, partly because Yoani is probably the most visible and celebrated dissident on the island, but mostly because this just doesn’t happen in Cuba.

The next statement is also prepared, as is the next: All three of them speak in the same fluent cadence of declaiming, of oracular truths, of nailing lies. All three (all bloggers) are intent on their text, oblivious to the flapping of the bird’s wings, which is amusing to everyone else because it adds an element of the ridiculous.

Another woman takes the mic and speaks “en contra,” the anger rising in her voice. People finally settle down, and in the quiet the reverb completely fills the space. A smattering of whoops and applause, as with the others, and then the din starts right back up.

With the exception of the bloggers and a couple of others, the people who are speaking seem unsure of themselves up onstage. Sometimes the awkwardness lands lightly, and sometimes not. There are a few flashes of the operatic oratory that’s been a staple of the island’s public space since that day in 1959 when another dove had landed on another speaker’s shoulder. A young guy bounds onto the stage after the longest of several uneasy pauses, and as he exhorts people to speak up he gestures in a classic Fidel-esque kind of way, his hand slicing up and down with a pointed finger. It’s not evidently a parody. After him a skinny teenager blabs on about doves, and their meat, and feathers—this time an unmistakable send-up of the Commandante. Rumor had it that he was trying to impress a girl.

The politics are all over the place. Someone talks about hunger strikers in Cuban prisons. Someone with bad Spanish pumps his fist in the air and shouts old slogans to the slightly embarrassed crowd. A woman declares that “millions of children are starving. None of them Cuban!” One guy pleads—addressing the authorities this time, not the assembled crowd—that the performance not be banished from the national media (it was). Eugenio Valdés, a respected curator and critic (also living abroad) goes up and refers to an infamous meeting in the early years between Fidel and intellectuals. “I only know that I am afraid,” the great writer Virgilio Piñera is said to have remarked on that occasion. “Me too,” says Eugenio, and there’s a small grace note as he walks away. There are some soapboxers, denouncing everything from a recent home raid by State Security, to the unavailability of biennial catalogues for Cubans (there are plenty for foreigners), to violence against women in Ciudad Juárez. The level of polemic rises and falls. A woman screams into the mic. When someone asks for a minute of silence, “for ourselves,” it’s the first and only time that the room’s energy focuses.

People are constantly gabbing and joking, and sometimes they look amused by what’s being said or done onstage—even if it’s very self-serious. They’re behaving like an audience, in other words, rather than a multitude, enjoying the performance as performance more than getting whipped up by it. It’s only when there’s a rallying shout from someone near the end that you realize the absence of things like that—no chanting in unison, no sense of the crowd organizing itself into a voice. There’s no big catharsis, no major poetic moment, just a lot of stabs in various directions.

It’s a strange kind of narrative space, never accumulating energy or building in some dialectical kind of way. The long stretches of dead air never find a rhythm, and the reactions to each speaker pass quickly. The waiting puts pressure on whatever happens next. Time tends to draw out. It’s a meandering and unsettling kind of thing, impossible to discern a shape from within it, so whatever is around the edges takes on weight: the jostling and chatting, the constant flashes (meant to make people feel more important), the booming sound and difficulty of hearing, the flapping bird. At times it feels like the whole thing might just drag to a halt, nobody doing anything and nobody knowing if that would be the end of it or if it was a waiting game, where as long as people stuck around it would keep going. So Tania at least gave it a shape by giving it an end. It did seem odd that she thanked the Cubans specifically.

What happened that evening read differently to different people. An open mic and people demanding freedom was just extraordinary in the Cuban context, even though it was also something closer to political kitsch. It’s possible that the discrepancy owed a lot to the incompatibility of the various historical memories in the crowd. Judging from reactions at the time, the awkward and self-conscious declarations were moving for some but depressing evidence for others: “nothing more than the reflection, and maybe the least of the consequences, of the constant ‘nobodyizing’ [ninguneo] that we’ve been subjected to for so many years,” as one guy put it. “Fleeting phrases, choked verbs in which, with some exceptions, you could see the thick and viscous patina of fear.”2 Depending on whom you asked, what happened was the germ of awakening defiance, the cynical maneuvering of regime strategists, evidence that “freedom” means the same thing everywhere, and, equally, evidence that a concept of freedom transported from one place to another will turn into a performance rather than a realization of itself. The performance did once again ratify Cuba as an incubator of radical contemporary art, and it convinced some reporters that change was definitely coming on the island. It was proof, for others, that the regime always gets the last laugh.

The huge curtain made everything look important. The incandescent yardage stretching up over the speakers’ heads, the symmetrical tableau, the cameras, the lights facing one way at the stage and the other to catch the crowd, all lifted the patio and the hour into an iconic frame. The people were dwarfed by history and larger than life. Still, it all unfolded in a real time full of stutters, gaps, and miscues: The instantly recognizable image was dragged to the brink of itself by that buzzing, distracting mirror. There was tension between the naturalism suggested by the artist yielding control and the performance’s extreme artifice—what was offered was not in any sense normal. All this made it charged and unsettling, and the obvious, looming question—would the police come?—made it jittery too.

There was wonderment that such a thing was allowed, and the first part of the answer why is that there were just too many foreigners for anything serious to go down. Anyhow, in Cuba, art—as the event made absolutely plain—is given a lot more latitude than other kinds of expression, at least as long as it’s somehow useful to the government’s overall objectives (an “aesthetics of foreign policy,” Laura Kipnis called it).3 There are probably other reasons, like that it could provide catharsis in the paralyzing, Brechtian sense, and some even speculated that the performance gave the regime an excellent opportunity to take the temperature of general discontent, “recalculate their methods, and more.”4

Another part of the answer has to do with the artist’s status: She had to be firmly inside and outside at the same time, or she could never have pulled it off. Without her international reputation built around confrontational “political” work she’d be just another troublemaker, and the performance at the mic would have had to be read strictly within the Cuban context. But if the art world calls her “daring” and “important,” then that makes it inconvenient for the Cuban authorities to call her counterrevolutionary. A couple of things are going on here. First, the relatively level playing field puts us more in the realm of constraint than brute force, and, second, they were playing from different sources of strength. Yoani’s fatal flaw was to operate from the same system, and with the same language, as the regime, but the artist brought in an external source of leverage and deployed a compensatory form of power. She changed the price of responding to the provocation.

But anyhow, the piece took place as much offstage as on. As usual in Cuba, it had to be approved before it could be allowed and described and explained in detail in order to be considered. Though they’re the work’s hidden aspect, those negotiations were quite possibly the most artfully elaborated elements of the whole piece. By her own account, the artist confessed her worries in the course of those exchanges, but she gave them such an anodyne face that the image of what might go wrong—either total silence or joking around—didn’t sound all that bad. The ostensible framework for the performance was a series called Tatlin’s Whisper, which consists of restaging media images that have gone stale from over-familiarity. (Earlier pieces included herding people around a museum lobby with mounted police and a bomb-making workshop.) It’s hard to believe that officials could have been ingenuous enough to buy the idea that, in restaging Fidel’s early triumph—sort of—the artist was intent on giving the audience a “direct experience” of that historic moment, one that they’d “understand and that [would] belong to them because they have lived it.”5 It’s hard to believe that they might have fallen for her misdirections, but trying to divine what any of the players may have really had in mind is a fool’s errand, and the main point is probably just that the various parties saw strategic convergences in the scenario, if not converging interests.

What We Were Arguing About

By splitting off an hour from the usual state of things, the performance made the lack of free speech in Cuba palpable: It made truth distinguishable from power. This didn’t really resolve anything in a large or empirical sense, because it did nothing to alter the base condition of an entire society being silenced. It’s a good (and painful) question whether we can expect art really to do anything about that, and the discrepant reactions to the performance had mostly to do with how actively and directly anyone thought that art can or should try to change the world.

In any case, the hour was extraordinary and historic, and it happened because it was art; that is, it made a space that would only be allowed to exist in art. It unsealed art’s relatively permissive space and made it accessible to people who were normally at the bottom rungs of privilege. (From the bloggers’ perspective, I suspect that the “artness” of the occasion was secondary at best, hence Yoani’s statement the next day that “it was an artistic action, but there was no game in the declarations we made. Everyone was very serious.”)6 It was a masterful deployment of art’s privileged status, but nonetheless it was definitively art, and that’s why, even afterward, official retaliations were minimal. Bruguera’s ending the piece after an hour was the final feint: It really was (just) art, that seemed to say. It would not be allowed to become something outside the boundaries that had been announced; it would not be allowed to continue until it found its own natural end.

Part of the work’s punch came from the fact that, beyond sharing her leverage, Bruguera flaunted it. It was a tricky balancing act: Without identifying with either of two irreconcilable parties, she acted as both. This flew in the face of all those ideas about artistic ethics that insist on rejecting and opposing the apparatus in order to remain outside, uncoopted, and uncorrupted. It also played against the rules of the game of revolutionary compliance, for obvious reasons. Bruguera’s personal capital has both cultural and political valence, it works in both the art world and in Cuban circles of power, and each part has been built up by virtue of the other. The toughness of that double origin kept the work from lapsing into the romantic melancholy of so much political art and steered it clear of romantic protagonism. But the failure of the performance in rhetorical terms (the bulk of what was said was just too null, in either political or poetic terms) was the orphan space where it landed—not exactly art, not exactly insurrection. Although the set had pointed in a more imperial direction, what played out on it was something more like a real—as opposed to ideal—political subject: impeded and constrained, implicated in all kinds of ways, struggling for words and struggling with the fact of being made public. Rancière has been unsympathetic on the question: “Those who want to isolate [art] from politics,” he says, “are somewhat beside the point, but those who want it to fulfill its political promise are condemned to a certain melancholy.”7

Another thing we were disagreeing about was spectacle. There have been all kinds of fantastic capacities imputed to theater: It’s “an assembly where the people become aware of their situation and discuss their own interests,” as per Brecht, or “the ceremony where the community is given possession of its own energies” (Artaud).8 Although those two doctrines differ in important ways, they agree on the problem of spectacle, and while the argument I’ve been sketching about Bruguera’s piece fits pretty well with those doctrines in terms of what happens to those who are assembled in a wor...