![]()

PART ONE POLITICS OF

THE PERIPHERY

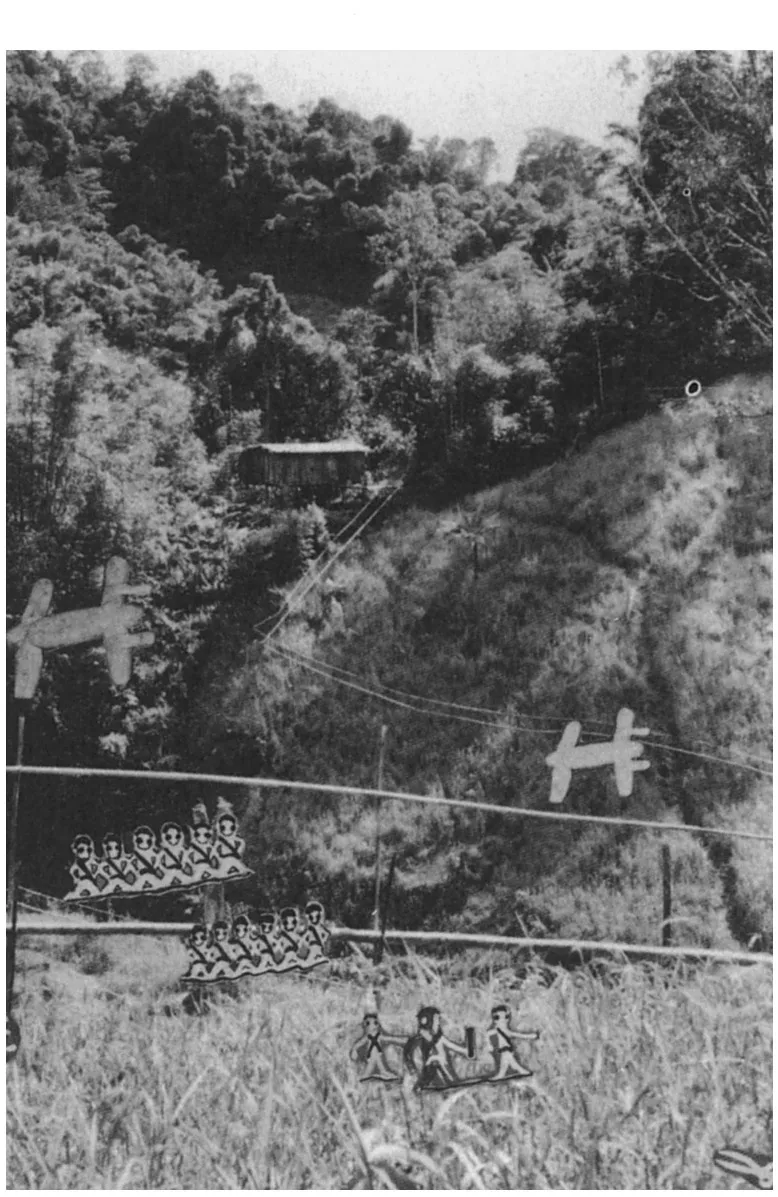

“. . . dressed all in black, dressed all in green”:

Spirits, like soldiers, militarize the everyday

landscape. Here, the spirits are rice-flour

offering cakes.

Central to the problem of this book is an unintended Meratus challenge: Everyday Meratus existence offends official ideals of order and development. Two aspects of official definitions are crucial to Meratus negotiations of their political status. First, national political culture encourages portrayals of the Meratus as stuck in a timeless, archaic condition outside modern history. Second, this same official framework shows Meratus mobility across the landscape—as well as the limited accessibility of the forested mountain landscape for administrative travellers—as cause and consequence of their disorderly, precivilized character.

On the whole, it seems fair to say that Meratus reject the notion that they are outside history, or that their relation to the state and its “civilization” is new. Instead, they invoke a long, continuous succession of rule in which contemporary state policies are a minor variant. Their responses to state initiatives draw on this history—arguing for its relevance even as their arguments go unrecognized by government officials. Similarly, Meratus imply that mobility, rather than isolating them, increases their access to external power and knowledge. Meratus interpretations refuse the state’s implied contrast between administrators’ rights to unhampered mobility and the necessity of an immobilized subject population.

This section introduces state rule in the Meratus Mountains. I describe “the state” and “the Meratus” as coherent, stable social elements because it is within such an imagined opposition that particular government officials and particular Meratus begin contemporary political negotiations.

Very different kinds of “states” have ruled in southeastern Kalimantan. Between the fourteenth and nineteenth centuries, various kingdoms claimed sovereignty. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the area came under Dutch colonial rule. Since 1949, the Meratus Mountains have been part of the Indonesian nation-state. Each of these “states” offered a different technology of rule.1 Dutch colonialism, for example, invented “ethnic” differentiation as a feature of political administration; the earlier kingdoms seem to have sponsored a much more fluid traffic in cultural difference.2 The Dutch codified adat law and stabilized communal boundaries.3 They also built roads, established administrative boundaries, and introduced the conceptual grids for maps and censuses. These have continued to inform the Indonesian nation-state, even as it has sponsored new involvements with national political consciousness.4

Meratus Dayaks have been so peripheral to each of these designs of power that until recently they were barely noticed by regional centers. The classic Banjar chronicles fail to mention marginal populations.5 Dutch accounts note the Meratus only as scattered and untroublesome survivors of many years of Banjar influence.6 No longer authentic, their customs were hardly worth codifying. Ironically, under national rule, a number of reports have appeared in which the Meratus finally have become an authentic savage object.7 Yet these reports only push Meratus farther to the margin of nation-building.

From a vantage point in the Meratus Mountains, continuities in state power over time become more apparent than the distinctions between eras. First, several centuries of state policies support a divide between Banjar and Meratus and an asymmetrical forest-products trade; Banjar funnel Meratus products to extra-regional sources. Second, Meratus leaders have long been assigned formal titles in state bureaucracies, to which they owe sporadic ritual submission. On occasion, states demand tribute in local products. Third, Meratus lands have been the ground of varied military operations, and the military has long been among the key contacts between Meratus and the state. These continuities are important within Meratus perspectives; I use them to introduce Meratus history in slightly fuller detail before returning to contemporary New Order policies.

Like Dayaks throughout southern Kalimantan, Meratus have long collected forest products for world markets. Before European control of the area, kingdoms in the Barito River delta and on the east coast attempted to regulate this trade. Court centers in the region first developed during the fourteenth century, perhaps under the sponsorship of the Javanese kingdom of Majapahit.8 By the late sixteenth century, a harbororiented “Banjar” kingdom in the Barito River delta had grown to considerable regional power. This kingdom, in alliance with the Javanese state of Demak, sponsored conversions to Islam. This began the process in which Islam and court history became central to the identity of those who came to be called “Banjar.”9 “Dayaks” are those outside of Islam and its political sponsorship—but not outside regional political and economic relations.

As the Banjar kingdom expanded with the state-sponsored spread of pepper plantations in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, “Dayaks” were either incorporated or pushed back from Banjar centers.10 The rough hills of the Meratus Mountains form an island surrounded by Banjar expansion. Even as pepper came to predominate the kingdom’s trade revenues, however, Dayak-gathered forest products remained important; the state’s harbor control created a Banjar-middleman role in this trade.11 Some Meratus still have eighteenth-century European coins from this trade. Meratus oral histories variously mention ritual tributes to the Banjar kingdom or the smaller courts of the east coast. By the early nineteenth century, a few Meratus areas were paying tribute in gold; the clay excavations where people dug to gold-bearing gravel remain to remind current residents of these taxes.12

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the Dutch became increasingly interested in controlling southern Kalimantan.13 European and Indonesian sources tend to disagree, however, on just when and how Dutch control was accomplished. European and North American sources note that a Banjar sultan ceded all Kalimantan territories except the central area of the kingdom to the Dutch East India Company in 1787, and that the Dutch colonial government abolished the Banjar sultanate entirely in 1860.14 Many Kalimantan sources do not find the former treaty significant and point out that Dutch attempts at takeover in the nineteenth century stimulated a war in which the last Banjar patriots only surrendered in 1905.15 The year 1905 also marked the Dutch abolition of the last small southeast coast kingdoms, rarely mentioned in European histories.16 In either case, Meratus remained peripheral subjects.

Dutch colonial rule was accompanied by new export-production schemes. Rubber was first planted in South Kalimantan in 1904; by the 1920s, the area had become rich with rubber in every sense.17 (Photographs from this period show Banjar markets jammed with shiny new cars.)18 Banjar pressed into the western Meratus foothills with rubber plantings, pushing back Meratus settlement. The worldwide depression of the 1930s, however, hit rubber producers severely. In 1934, the Dutch joined a transnational rubber-regulation program to limit production.19 Despite low prices, the succeeding few years were important in stimulating rubber-growing by Meratus in the foothills. Dutch officials slowed the expansion of Banjar holdings in the foothills. Meratus gained a share of planting and sales quotas. (Older foothill Meratus remember a “Mr. Coupon” [Tuan Kupun] who handed out the quotas.) Meratus were also hit by a colonial head tax, in the 1930s, which was paid in cash; this encouraged them to engage in cash-crop production as. well as wage labor.20 Some Meratus worked in Japanese pepper plantations on the southeast coast to meet their taxes. As World War II approached, however, the plantation owners were recalled to Japan, and their Meratus workers returned to the mountains.

The Japanese returned to invade Kalimantan in 1942, from the southeast coast, and maintained bases east of the Meratus Mountains throughout most of the war. Japanese troops marched back and forth across the mountains to the populous west-side centers of regional administration. (Meratus variously remember their alien discipline, their hiking sticks, their condoms.) Yet this was neither the first nor the last military disruption in the Meratus Mountains. In the Dutch-Banjar war of the late nineteenth century, Banjar forces took refuge in the mountains.21 Before this, the soldiers of the Banjar courts, as well as Dayak raiders, sought mountain victims for head-taking or other sacrifices.22 After World War II, when the Allies returned Kalimantan to the Netherland Indies Civil Administration (NICA), the mountains remained an arena of military action as anticolonial nationalist Banjar moved into the hills and were followed by NICA forces.23

The Republic of Indonesia won full independence in 1949. By the mid1950s, another military interaction had permeated the mountains: Islaminspired anti-Jakarta rebels established guerilla bases in the eastern Meratus “jungle” and crisscrossed the mountains, running from government troops and connecting with supportive Banjar villagers to both the west and the east.24 The rebellion was finally subdued in 1965. This was also the year in which the army launched operations against the Indonesian Communist Party and its supporters; a few Meratus in the western foothills were imprisoned (along with Banjar and other Dayaks) during this campaign. By the late 1960s, outspoken dissidence and rebellion in the region had been quelled. However, the armed forces remained prominently visible throughout the 1970s and 80s. Every Banjar town large enough to support a weekly market also has an armed forces post.

Postcolonial administrative intervention in the Meratus area was sporadic until the 1970s, when state expansion into the Meratus area became more sustained. In the 1970s, the Suharto regime responded to international pressure by taking more direct military and economic control of the country’s remote and resource-rich corners. Rainforest timbering has become an important development sector, with concessions falling under the control of army generals and their business partners.25 Meanwhile, armed resistance to state expansion in East Timur and Irian Jaya has served as a continuing reminder of the possibility of rebellion in rural and even “tribal” areas.26

In this context, several state agendas for the Meratus Mountains have emerged. First, forested areas were divided into timber concessions. (By the late 1970s, the east side was being logged; much of the west side was, from colonial times, a watershed-protection area. Despite this, by the mid-1980s, logging was moving rapidly through west-side forests.) Second, new sites for Javanese transmigration were opened. (Several sites were located in South Kalimantan; I am unaware of any currently within the area of Meratus settlement.) Both programs assume the area as unpopulated; a third program, however, targeted local people. This is the government program for the Management of Isolated Populations, who are to be moved into resettlement villages, making forested land available for national priorities. “Disorderly” farming practices—that is, shifting cultivation—are to be controlled for reasons of both order and development.27

By the early 1980s, the western foothills of the Meratus Mountains were the site of about a dozen resettlement villages.28 Meratus resettlement had a number of direct, immediate consequences. First, it opened the foothills to Banjar immigration, through state guarantees of services and “free” land. Second, it hastened degradation of foothill forests to brush and grassland by setting up densely contiguous farming plots and rapid cycling of swiddens and forest regrowth. Third, it formed pockets of dangerous health conditions, as Meratus were encouraged to eliminate, wash, and drink from the same crowded streams. Fourth, it laid the groundwork for dispossessing Meratus of land and forest resources by stressing the powerlessness of the Meratus in relation to state policy.

Other changes were perceived locally as benefits. Some children were attending school. New, closer periodic markets were set up. And resettlement residents had the political advantage of being described as models of state cooperation rather than as renegades. These political advantages sometimes sparked considerable enthusiasm about participation in “development.”

In the 1980s, police and administrators only rarely ventured beyond the motor vehicle roads that ended at the borders of the Meratus area. Officials defined the Meratus area in relation to their own awkward, incomplete penetration; for most, hiking in the Meratus Mountains was uncomfortable, frightening, and confusing. Yet state officials assumed that Meratus ranged freely through the area. Thus, they constructed a gulf of inaccessibility between the “civilized” and the “nomadic”—albeit a gulf structured into zones of more or less reachable destinations. The possibilities for supervision, taxation, law and order, and development— as well as the very definition of the Meratus as a group of not-yet-citizens—were understood by state officials in relation to the difficulty of administrative travel.

Almost all the Meratus I knew travelled extensively. In contrast to the state stereotype of Meratus nomadism, however, Meratus travel did not assume an undifferentiated landscape. For each traveller, some places were more familiar and socially accessible than others. Meratus understandings of the social landscape begin with the notion of unevenness in the ease with which one travels to particular places. Great travellers— shamans and political leaders—are distinguished by their ability to forge links with less and less familiar places of power and knowledge as they overcome the dangers of travel.

Taken together, these various understandings and practices of travel (one could add those of Banjar pioneers, traders, and the occasional tourist or anthropologist) make up what one might call, following Foucault, a semio-technology of power and knowledge. The meanings and mechanics of difficult hiking anchor debates and discussions of Meratus marginality; they create this marginality as a contested domain. Travel shapes state interpretations of the Meratus and Meratus interpretations of the state.

The travel orientation of the administrative gaze can be seen, for example, in the construction of a “zoned” Meratus social geography. Resettlement policy and the extension of more direct government control has affected the entire Meratus area, though unevenly. Even in areas rarely visited by officials, Meratus have responded to the threats and promises of state expansion, but not in the same ways as those more regularly observed. Indeed, state expansion has re-inscribed the division of the Meratus area into three separate zones of administrative reach.

The western foothills are an area of nucleated settlements, many of them set up to copy or comply with the government’s resettlement model. (In some river valleys, however, Meratus live in collective halls that house up to thirty families.) There are a few areas of scattered settlement, with houses on fields; given state demands, this has been hard to maintain. The western foothills are the most densely populated Meratus area. Tropical grass fields a...