NOTES

INTRODUCTION

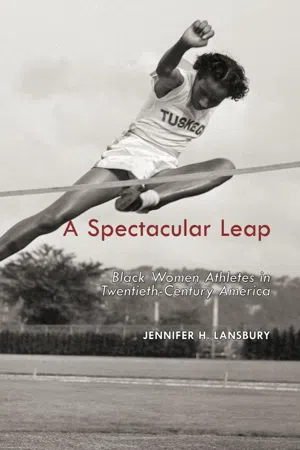

1. The African American Pittsburgh Courier provided the description of Coachman’s 1941 high jump victory. “Tuskegee Lassie Goes Up and Over to Retain Title,” Pittsburgh Courier, 29 July 1941, 16.

2. Coachman’s married name is Davis. Alice Coachman Davis, Interview by author, tape recording, Tuskegee, Alabama, 10 February 2003.

3. Many scholars have already explored women athletes’ navigation of such stereotypes. Susan K. Cahn, Coming on Strong: Gender and Sexuality in Twentieth-Century Women’s Sport (New York: Free Press, 1994), is the seminal book-length study into femininity/sexuality, class, and women in sport, and its insights remain extremely relevant. Other important works include Gwendolyn Captain, “Enter Ladies and Gentlemen of Color: Gender, Sport, and the Ideal of the African American Manhood and Womanhood During the Late Nineteenth Centuries,” Journal of Sport History 18 (Spring 1991): 81–102; Mary Jo Festle, Playing Nice: Politics and Apologies in Women’s Sports (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996); Cindy Himes Gissendanner, “African-American Women in Competitive Sport, 1920–1960,” in Women, Sport, and Culture, ed. Susan Birrell and Cheryl L. Cole (Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 1994); Gissendanner, “African American Women Olympians: The Impact of Race, Gender, and Class Ideologies, 1932–1968,” Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 67 (June 1996): 172–82; Patricia Vertinsky and Gwendolyn Captain, “More Myth Than History: American Culture and Representations of the Black Female’s Athletic Ability,” Journal of Sport History 25 (Fall 1998): 532–61; Rita Liberti, “‘We Were Ladies, We Just Played Basketball Like Boys’: African American Womanhood and Competitive Basketball at Bennett College, 1928–1942,” Journal of Sport History 26 (Fall 1999): 567–84; Pamela Grundy and Susan Shackelford, “Black Women Embrace the Game,” in Shattering the Glass: The Remarkable History of Women’s Basketball (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005); Martha Verbrugge, Active Bodies: A History of Women’s Physical Education in Twentieth-Century America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012).

4. While the work of many theoretical scholars has been transformed by what Kimberlé Crenshaw called the intersectionality of race, class, and gender, my own approach is grounded less in theory and more in historical analysis and narrative. Kimberlé Crenshaw, “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color,” Stanford Law Review 14 (1991): 1241–99. For a recent overview of the theory, see Michele Tracy Berger and Kathleen Guidroz, ed., The Intersectional Approach: Transforming the Academy through Race, Class, and Gender (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009).

5. This narrative approach addresses the problem of limited sources, especially for the athletes who competed during the first half of the century. The black press began following women athletes within the black community as early as the 1920s, and, by mid-century, the white press was writing about them as well. However, the details that can be gleaned from the sports pages—scores, descriptions of games, matches, and track meets, and the names of players—often generate more questions than they answer. Where possible, interviews, personal papers, and autobiographies supplement the press accounts, yet oral and archival information are not abundant for “famous” athletes and virtually nonexistent for many women who competed against and alongside them.

6. Jacqueline Jones’s monograph remains a valued overview of the work lives of black women. See Jacqueline Jones, Labor of Love, Labor of Sorrow: Black Women, Work and the Family, From Slavery to the Present (New York: Vintage Books, 1986).

ONE

1. Randy Dixon, “Ora Washington, E. Brown Cop Net Crowns,” Philadelphia Tribune, 29 August 1929, 10. For Washington’s strengths on the court, see Sam Lacy, “Althea Gibson Vs. Ora Washington for Women’s All-Time,” Baltimore Afro-American, 17 September 1953, 13.

2. Pamela Grundy argues Washington was the “first black female athletic star” in the African American community and, while I have paraphrased the title, I certainly concur. See Pamela Grundy, “Ora Washington: The First Black Female Athletic Star,” in Out of the Shadows: A Biographical History of African American Athletes, ed. David K. Wiggins (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2006), 78–92; “Bennett Cage Team Facing Two Games,” Greensboro Daily News, 9 March 1934, 12.

3. For the preeminent work on the changing perceptions of gender and sexuality within women’s sport, see Susan Cahn, Coming on Strong: Gender and Sexuality in Twentieth-Century Women’s Sport (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994).

4. I am indebted to Pamela Grundy for sharing with me her interview of Washington’s nephew, J. Bernard Childs, and for her previous research into Washington’s background. See Grundy, “Ora Washington: The First Black Female Athletic Star,” 78–92.

5. Because Virginia, still recovering from the financial setbacks of the Civil War, did not issue birth certificates from 1896 to 1912, the exact date of Washington’s birth is unknown. Grundy, “Ora Washington: The First Black Female Athletic Star,” 81. The age I use for the introductory paragraph is calculated from an age reference Washington makes to a sportswriter late in her career. See “Injury Forces Ora Out of Singles Play,” Baltimore Afro-American, 9 August 1941, 20, in which Washington says she is forty.

6. Grundy, “Ora Washington: The First Black Female Athletic Star,” 80–81; J. Bernard Childs, Interview by Pamela Grundy, Bowling Green, Virginia, 4 October 2003.

7. Grundy, “Ora Washington: The First Black Female Athletic Star,” 81–82.

8. Literature on the Great Migration is vast, particularly in terms of the conflation of problems driving blacks north and the emergence of black communities in northern cities. Some important works include Peter Gottlieb, Making Their Own Way: Southern Blacks’ Migration to Pittsburgh, 1916–1930 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1987); James R. Grossman, Land of Hope: Chicago, Black Southerners, and the Great Migration (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989); Milton C. Sernett, Bound for the Promised Land: African American Religion and the Great Migration (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1997); Victoria W. Wolcott, Remaking Respectability: African American Women in Interwar Detroit (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001); James N. Gregory, The Southern Diaspora: How the Great Migration of Black and White Southerners Transformed America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005); Davarian L. Baldwin, Chicago’s New Negroes: Modernity, the Great Migration, and Black Urban Life (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007); Lisa Krissoff Boehm, Making a Way Out of No Way (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2009); and Isabel Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration (New York: Random House, 2010). In contrast to the more traditional narratives on the causes of black migration during this period, Steven Hahn places the movement into a long-standing African American social and political framework. See Steven Hahn, A Nation Under Our Feet: Black Political Struggles in the Rural South from Slavery to the Great Migration (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2003), 465–76.

9. The many artistic facets of the Harlem Renaissance have resulted in an extensive literature on the subject. For example, see Nathan Irvin Huggins, Harlem Renaissance (London: Oxford University Press, 1971); David Lewis Lettering, When Harlem Was in Vogue (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1981); Cary D. Wintz, Black Culture and the Harlem Renaissance (Houston: Rice University Press, 1988); George Hutchinson, The Harlem Renaissance in Black and White (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1995); Cheryl A. Wall, Women of the Harlem Renaissance (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 1995); J. Martin Favor, Authentic Blackness: The Folk in the New Negro Renaissance (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1999); and James F. Wilson, Bulldaggers, Pansies, and Chocolate Babies: Performance, Race and Sexuality in the Harlem Renaissance (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2010).

10. Allen Guttmann, Women’s Sports: A History (New York: Columbia University Press, 1991), 106, 112; Vassar Catalogue; quoted in Guttmann, Women’s Sports, 113.

11. Guttmann, Women’s Sports, 113–16. For more on the emergence of women’s sports in the U...