![]()

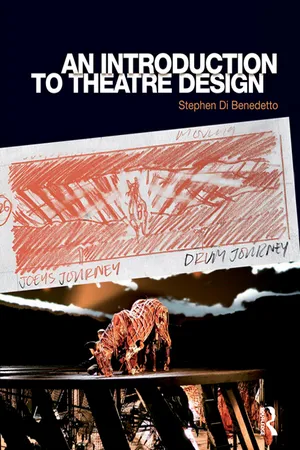

1 The theatre designer’s job

Key Topics:

What do theatrical designers do?

• Set design, costume design, lighting design, and sound design

An overview of the designer’s job from conception to realization

• Ground plan, rendering, models, load-in, and tech rehearsals

• Proscenium, thrust stage, arena, black box, non-theatre spaces

Designers looking at the world

• Peformance designers and scenographers

Examples:

• August: Osage County (2008) / Todd Rosenthal

• Hamlet (1909) / Edward Gordon Craig

• Death of a Salesman (1949) / Jo Mielziner

• The proscenium configuration

• Berkeley Rep’s thrust stage

• An adapted proscenium configuration

• A three-quarter thrust configuration

• H.G. (1995) / Robert Wilson

Theatre is a collaborative art and it is hard to define where particular visual ideas come from and why they take on the final form that they do in production. A theatre designer is a person who creates and organizes one of the visual or aural aspects of a stage production. Theatrical designers sometimes seem mysterious to actors and audiences because their work takes place out of sight. Where do their ideas come from? Why do they make the choices they do? How can one evaluate the creativity of their work? There is no simple answer to these questions since theatre production is an ephemeral art that disappears as soon as it is created. One must first learn to read those images like we do play texts in order to understand what the role and skills of the designer were as the designs were created.

There are four main types of designers that create the visual and aural world of a play. They are the set designer, costume designer, light designer, and sound designer. While they all make use of the same principles and elements of composition their tasks differ slightly. Even these divisions are artificial, for a set designer often works as a costumer, in the United Kingdom, or even as a director at times. This chapter outlines the basic job descriptions of each type of designer and begins to show you their approach to the design process.

What do theatrical designers do?

A theatre designer is a person who creates and organizes the visual or aural aspects of a stage production. Based on practical necessity, convention has developed in such a way that the set designer leads the design process. The set design is often the first thing audiences see when they walk into a theatre. This is their first look at the production and can set its tone, reveal the time or locale, set up the basic style, establish mood and atmosphere, and introduce the production’s concept. It can suggest a lot about the kind of people who will inhabit this stage world before we meet them. The scenic designer collaborates with the director and the other designers to create a production concept that integrates actors, text, and environment. Once built, the adjustment of specific details of the set design is less flexible than those of costume, for example, because being a fixed set of staging it is expensive to change. Consequently the set designer will have initiated the colors and tones, and the general feelings of the picture that the audience sees onstage.

Scenery, costumes, lighting, and sound work together with the actors to create an ever-changing event. For example, if you look at Todd Rosenthal’s set for August: Osage County, we can see the Weston home, but we cannot develop an understanding of the nuances of protagonist Beverley’s life in the absence of the other aspects of the theatrical design. We cannot know that the windows are blacked out because the characters refuse to acknowledge certain facts about the family. The setting on its own cannot provide us with the meaning of the play; it needs to be integrated with the embodiment of the text by the actor as well. By the end of the play we will understand that the house helps illustrate the history of the conflicts between the different family members.

© Todd Rosenthal

This full model of Todd Rosenthal’s set for the original Broadway production of August: Osage County (2008) shows the basic configuration for the Weston family home. However, it does not tell us anything about the secrets that each of the family members have, or the traumatic arguments that will unfold here. It is only after we see the actors and listen to the text that we can see what elements in the set reinforce the dark undertones of the major themes. Rosenthal does not create separate rooms for each location, but rather divides the space into distinct zones. These rooms are understood to be real spaces. Rosenthal leaves the further definitions of these spaces to the lighting designer and the actors. For example, Ann Wrightson, the lighting designer, may only light one zone at a time to concentrate the audience’s attention, or use light to reveal more than one zone to suggest activities in one zone affect the zone where the scene occurs. Rosenthal selected details to evoke the social context of real spaces.

The scene designer is responsible for the creation of the stage set. It can be anything from a bare stage to a huge spectacle complete with exploding volcanoes or waterfalls. No matter whether it is simple or complex, every set has a design. Even the act of arranging chairs as part of Eugene Ionesco’s The Chairs can be considered as design practice. Related to stage design, is the job of production designer in the film industry. Whether a film is set on location or in a studio, the designers create a real object down to the last detail. Different from theatre design, the film medium’s detail, texture, and surface detail are more important than the overall look since the camera sees close up detail more than long shots. On the other hand, scene design for the stage differs from interior decorating in that it creates an environment and an atmosphere that are not finished until occupied by performers.

There is a great deal more to good set design than just making pretty pictures for performers to stand in. Effective set design involves supporting the idea of the play and the director’s interpretation, creating a dynamic space, which feeds the action of the play, the blocking, and the performances. Of equal importance, the set must give the audience, as well as the actors, a powerful and accurate sense of time and place.

Deborah Dennison

A designer does not create a space that speaks on its own, but creates a space that is defined by the actions of the actors inhabiting that space. Besides creating an environment, the scene designer also has to develop a design concept with a central design metaphor in order to distinguish realism from non-realism, to establish time and place, to set tone and style, to coordinate with other elements, and to deal with practical considerations of how the stage space will be used. The scenic designer does not work in isolation; the costume designer is responsible for the selection or creation of the outfits and accessories worn by performers, lighting reveals hidden aspects of the setting establishing such things as time of day, and sound designers handle the sounds and the amplification necessary to hear or to create mood or effect. Thus, we have to characterize the environmental conditions that the actors inhabit. Are the characters sitting around in a factory, and if so, when? Is it a safe place, decrepit, or abandoned? At a glance the audience will be encouraged to make judgments about that space.

Scenery, similarly to playwriting, directing, and acting is firmly rooted in everyday life. The choices that we make from the type of house that we buy to the neighborhood we live in show something about us. Does your living room have a television in it or bookshelves? These objects communicate different things about us and reveal our traditions, family background and perhaps even what we would like to become. When we first encounter a new room we are influenced by where we are, the temperature, the furniture, the seating configuration, whether it is a loud or quiet space, whether we are sitting on a new soft, black leather sofa or a blue polyester chair from the 1970s. Color, light quality, and temperature will affect our mood and how we see the world. We process this information quickly in our day-to-day interactions. We pick up whether we have walked into a dive bar or an exclusive nightclub. Is the space open and airy, or enclosed and dark? Immediately we understand whose place it is and what the owner is trying to convey about this place, and the types of activities that take place in the space. In theatre we take this knowledge for granted and make use of it to create fictional settings for audiences. Stage designers do not merely reproduce settings as if they were real, but rather deliberately choose elements to shape an audience’s impression of the worlds depicted within the play.

We are so acculturated to the presence of physical environments in each play that so closely suit its mood and meaning that we forget that theatre has not always been like this. Throughout most of theatre history the position of scenic designer did not exist – theatre makers used stock scenery or merely the space itself to serve as a setting. In Ancient Greece the skene was a fixed configuration used for all plays, while in the Renaissance there were only three stock sets (the civic, the domestic, and the pastoral) to serve for each genre of play. Therefore scenery did not differ considerably from production to production. Even today show-specific scenery is rare in traditional Asian theatres. For example, the Japanese Noh theatre has a stage that uses the same basic configuration of the stage and the ramp for all of their settings. They stand in for the location of all the plays. There is no literal representation of a real space, but rather it is a symbolic space that stands in for the location and context established by the music and the movements of the performers. Where couches, tables, and other scenic elements suggested a plausibly real space in August: Osage County, this space is fluid and is defined by use and convention. It is not meant to depict the world naturalistically. This type of platform scenery is used to indicate location because the action of the play is more important than the spectacle. Specificity in design became important in the early nineteenth century and not common until the twentieth century with the introduction of the ever-changing spectacle of melodrama and the desire to depict specific realistic locations. This was not possible until Adolphe Appia and Gordon Craig were able to liberate the representational stage from a static configuration into a practical playing space that is designed through the constantly changing dynamics of lighting, backdrops, and flats. Once the convention of creating localized setting became common, designers began to tailor their settings to the specific requirements of each play. Thus, for centuries the theatre used little more than the theatre space itself, with little embellishment, to stand in for environments. Likewise, prior to the late nineteenth century costume was not tailored specifically for each production. Actors chose their own costume from their private wardrobe, choosing garments that best showed off their features rather than with an eye to denoting status or character. Today costumes are chosen to support the definition of a particular character, not to show off the actor’s best features. Now we shape space to evoke moods and contribute to the audiences’ overall understanding of what the costumed characters unfold in front of their eyes.

Next in the hierarchy of designers comes the costume designer whose task is the visual embellishment of the actors on stage. The costume designer’s job is to transform the words of the film or play script into clothing and create the look of the characters. Costume design helps the actor to create believable characters by creating a visual narrative through the language of clothing. Within the framework of the director’s vision, costume designers will typically seek to dress actors to enhance a character’s persona, and/or to create an evolving palette of color, changing social status or period through the visual design of garments and other means of dressing, distorting, and enhancing the body.

Everybody has the ability to understand costume. We do it every day when we meet someone new. Our first impression of people we meet is likely to be influenced by their appearance. Are they neatly dressed in a suit or covered in tattered rags? Often the clothes we choose to wear reflect the way we feel and the way we want others to feel about us, while other times they reflect our circumstances or ability to care for ourselves. Our everyday interactions have taught us to assess how clothes reflect the people who wear them. Costumers harness that knowledge to show us who these characters are that we will be watching. At a glance the audience gains a huge amount of information about the status of, and relationship between, the characters. Before Miss Julie opens her mouth, her elegant, beautifully fitted white silk dress shows us something different about her than Jean’s black livery coat. A simple adjustment to the costume, a bloodstain on her bodice and a torn shoulder seam, or a straight razor sticking out of her clutch purse, enriches the audience’s perception of the character they see on stage. Even the type and quality of the materials used tells a story. The flow and weight of cloth may give information about the weight of the atmosphere – heaviness and thickness, diaphanous and airy all evoke related feelings in actors and audiences.

A fashion designer has a very different job than that of a costumer. High fashion reflects innovation and concept rather than a practical garment – it is defined to reflect the social and cultural world of the moment. The clothes that we see models wear are examples of a notion of style that will be obsolete in a season, rather than the reflection of the people who wear outfits in everyday life. In other words, fashion is about the display or defining of the fashion of a time and costume design is about representing or defining character. On the other hand, a theatrical designer has to imagine the people living in the clothes, behaving as they would in the time of the play to create a convincing picture of the characters. Costume designing is a balanced mixture of invention and practicality. Everything a designer tries to do with a design is chosen to strengthen the performance of the actors and the concept of the director. Most often, the work of the designers is scarcely noticed by the audience.

Lighting design shapes the way that audiences see the setting and costumes. The lighting designer’s task is to illuminate the actors so that the audience may see them while at the same time evoking mood or atmosphere. The scenic and costume designer know that their products look different under the lighting designer’s colored lights. Therefore it takes careful planning to ensure that the team will not have to make costly changes late in the game once lighting is added into the composition. A lighting designer handles all forms of illumination on the stage: the color of the lights, the mixture of the colors, the number of the lights, the intensity and brightness of the lights, the angle at which the lights strike the performers, and the length of time required for lights to come up or fade out. The light designer uses light to depict time of day and to evoke mood. We are all familiar with the ways in which light can affect our mood – on a bright and sunny day it is easier to get out of bed cheerfully, while on a cloudy, grey day it feels better to snuggle under the covers. It is the lighting designer’s task to set up these moods to color the audience’s perception of the actor’s actions. Lighting also helps to delineate different spaces on the stage, and to provide what looks like natural light to illuminate the setting and the actors.

Lighting was slow to develop ...