Upper Wharfedale, North Yorkshire

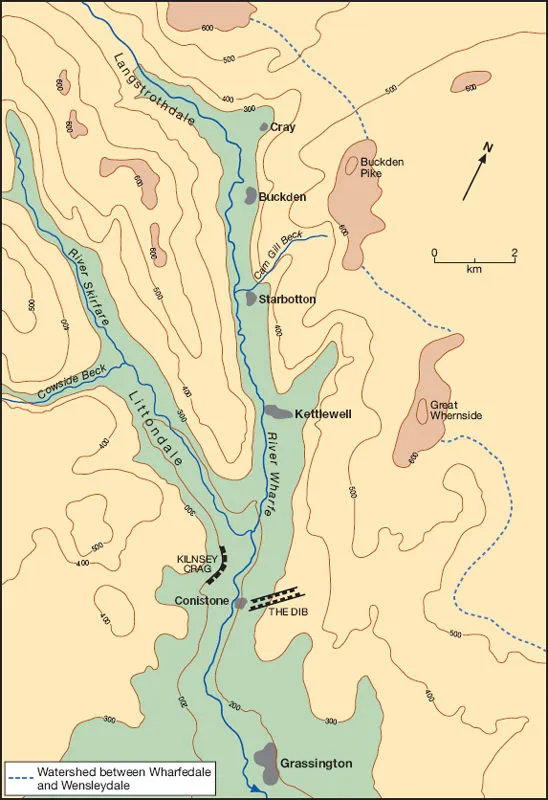

Situated some 45 km north-west of the city of Leeds in northern England lies the village of Grassington near the river Wharfe. The Wharfe is one of a series of rivers rising in the Pennine uplands of northern England and flowing eastwards to the North Sea. Grassington forms a ‘gateway’ to Upper Wharfedale, a 17 km steep-sided valley. Upper Wharfedale has one prominent right-bank tributary, the river Skirfare, occupying Littondale; other tributaries to the river Wharfe are a series of short, steep-gradient streams or becks entering on the left bank (Plate 1.1). Wharfedale is one of the dales in the Yorkshire Dales National Park, and is attractive to geographers and tourists alike (Figure 1.1).

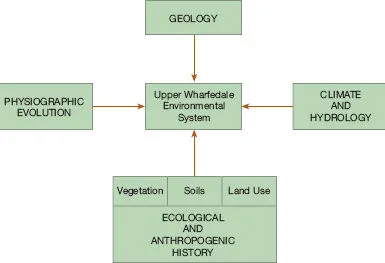

The attraction of Upper Wharfedale for visitors, as in all other dales in the National Park, lies in the unique assemblage of environmental elements which interact together to produce a landscape of great interest and beauty. Figure 1.2 shows how the four factors of (1) geology, (2) physiographic evolution, (3) climate and hydrology, and (4) ecological and anthropogenic history work together in this dale. By the word factor is meant a control which produces an effect. In physical geography it is recognized that these four controls act together in a complex manner to produce the totality of the physical environment. Another way of expressing this is to visualize the four controls as inputs into the total landscape system.

The geology refers to the physical and chemical nature of the solid rocks which underlie any part of Earth’s surface, together with associated structures such as faults and folds. It includes also unconsolidated sediments at the surface deposited by glaciers (till), rivers (alluvium) and slope-processes (colluvium or head). The physiographic evolution includes the present landforms of a region, their morphology (i.e. shape and size) and the manner in which they have been changed over time; the study of physiographic evolution is thus both spatial (i.e. of space) and temporal (i.e. of time). Climate and hydrology include the pattern of climatic elements (e.g. insolation, temperature, precipitation and wind) and the movement of water on or in Earth’s surface (i.e. the hydrological cycle). Ecological and anthropogenic history donate two influences of a biological nature; ecological controls focus on soils, vegetation (flora)and animals (fauna), whilst anthropogenic history includes the influences of human beings on all parts of the physical landscape, both now and in the past.

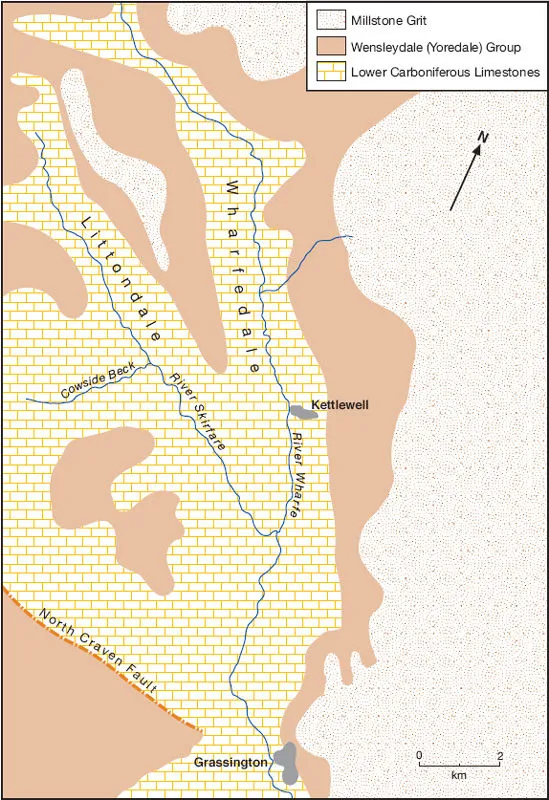

The geology plays a large part in forming this landscape (Figure 1.3). The rocks are horizontally bedded Upper Palaeozoic Carboniferous limestones and sandstones which have been deposited unconformably on Lower Palaeozoic Ordovician and Silurian rocks, and on Wensleydale Granite. The basal Carboniferous unit is about 360 m thick and comprises a series of limestones, the thickest being the Great Scar Limestone which outcrops prominently in Wharfedale and Littondale. Its name derives from the manner in which it weathers and erodes into terraces along bedding planes. Being well jointed, backwards retreat occurs by the successive fall of cube-shaped masses, thus retaining a vertical bare rock face, or ‘scar’. The Great Scar Limestone has been well studied, not least because of the striking variety of karst features to which it gives rise, both underground and on the surface (Waltham et al. 1997).

Overlying the Carboniferous Limestone Series are about 230 m of strata of the Wensleydale Group (previously called the Yoredale Series) consisting of cyclical deposits of limestones, sandstones and shales. In turn the Wensleydale strata are overlain by about 40 m of Millstone Grit, a series of coarse sandstones which give the highest flat-topped peaks in the Yorkshire Dales, as on the eastern side of Upper Wharfedale at Buckden Pike (702 m) and Great Whernside (704 m).

In terms of physiographic evolution, the most influential events were the many glacial episodes during the Pleistocene epoch of the Quaternary period (Atkinson, in Butlin 2003). During the most recent glaciation, namely the Devensian, glaciers entered Upper Wharfedale from local ice accumulation centres on plateau summits in the Pennine uplands such as Langstrothdale Chase, and flowed south-eastwards down Langstrothdale. On meeting Buckden Pike, the ice split into a stream flowing north-eastwards along Bishopdale and into Wensleydale and a stream flowing south-eastwards down Wharfedale. The Wharfedale ice was joined by Littondale ice, and the combined ice stream eroded the truncated spur of Kilnsey Crag in Great Scar Limestone (Plate 1.2). The power of glacial erosion is evidenced by the classic U-shaped valleys of Upper Wharfedale, Littondale and Bishopdale.

During periods of glacial retreat, moraines were deposited in valley bottoms and on lower valley side slopes. These are thought by some geographers to have initially dammed the river flow but to have been breached since. According to this hypothesis, the present flat alluvial floor of Upper Wharfedale held lakes in late glacial and early postglacial times. During deglaciation, when sub-surface drainage was prevented by permafrost, meltwaters eroded marginal channels along valley sides. At Conistone village the impressive ravine of Conistone Dib narrows to 1 m width in places, with fluvial potholes evident on the side walls. This dramatic gorge was sculptured by a glaciofluvial stream issuing from the front of or from beneath a retreating glacier (Plate 1.3).

Since the Pleistocene epoch, geomorphic activity in Upper Wharfedale has been of two main types. First, weathering and erosion of hill slopes have produced valley-side scars and small screes. Second, the channels of the river Wharfe and its tributaries have been carrying out fluvial action, with periods of incision (i.e. vertical erosion) alternating with periods of lateral channel migration and aggradation (i.e. deposition of sediments) to produce prominent alluvial terraces. River action in the early Holocene epoch was mainly a reworking of coarse cobbles and rocks from Pleistocene glacial materials, but more recent terraces are composed of finer-grained sediments produced by the erosion of hill slopes.

After the final retreat of the ice sheets and valley glaciers, the dale was recolonized by natural vegetation and associated wildlife. Birch and pine trees arrived quite quickly, followed by larger broad-leaved trees in early postglacial times. Ecological and anthropogenic impacts have had a great influence on the environmental systems of Upper Wharfedale ever since. Here, as wherever there are human settlement and l...