![]()

DEFINING THE GLOBAL SOUTH: REAL AND IMAGINED DIVIDING LINES

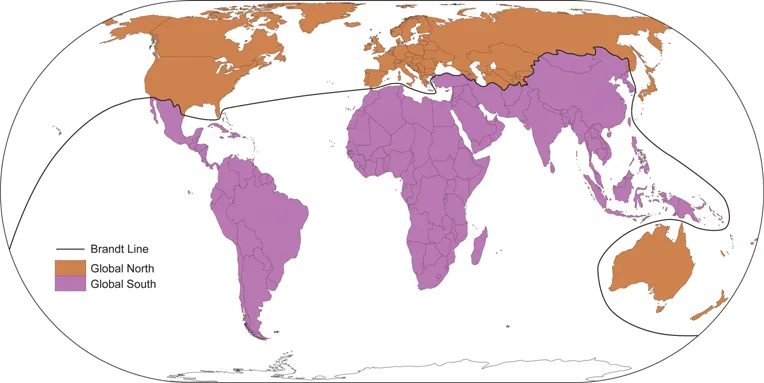

This is a textbook about the Global South – the parts of Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa and Asia that are often referred to as ‘the developing world’. That should be a simple enough opening sentence, but it hides some contentious definitions that go right to the heart of our reasons for writing this book. Had we been writing in the late twentieth century, these might have been brushed aside more easily: in 1980, ex-German Chancellor Willy Brandt chaired a Commission whose report, North-South: A Programme for Survival, presented a clear dividing line between a rich and powerful North and a poor and marginalized South. Positioned outside the capitalist ‘First World’ as well as the Soviet ‘Second World’, the Global South or ‘Third World’ was seen as something of a residual category, in need of sustained international assistance to ensure its development (see Pletsch, 1981). From today’s perspective, however, the world looks rather different. Rich and poor nations fall on either side of the Brandt Line (Figure 1.1): the old Soviet Union has dissolved, leaving new low-income countries (such as Tajikistan and the Kyrgyz Republic) in its wake; economic development in some parts of the South has given countries unquestionable ‘High Income’ status (such as South Korea, Singapore and Kuwait); and still others (such as Brazil, India and China) have become regionally or even globally powerful in their own right.

But although the Brandt Line no longer neatly divides rich from poor and the powerful from the powerless (and never did, given the variation that exists within as well as between countries), North–South divides are still important in shaping the way in which the Global South is imagined, talked about and studied today (Williams, 2011). Far too often in social science research and teaching, the Global South remains a marginal, residual and generalized category. It is vastly under-represented in research: Jonathan Rigg notes that only one-eighth of recent papers in top Anglo-American Geography journals were directly concerned with the countries and conditions of the Global South, despite the fact that it contains over 80 per cent of the world’s population (Rigg, 2007: 2). Not only this, but, when students in the North are introduced to the Global South through courses, it is often via a set of problems – such as poverty, debt or environmental degradation – and the development theories and policies used to ‘solve’ these. This conveys some useful information, and links with many students’ personal interests in issues of global inequality or ecological sustainability, but it does so with some considerable difficulties of its own. One of these is that it reinforces negative stereotypes of developing areas, and represents the Global South as a collection of places and peoples in need of external (i.e. Northern) intervention. Equally importantly, it can help to reinforce academic divisions that place the study of the Global South as a ‘specialism’ separate from the ‘mainstream’ of social science disciplines. Debates in social, economic and political theory often implicitly take conditions in the Global North as their point of reference. Where the Global South contributes to theoretical debate at all, it is often through the separate category of ‘development theory’, a point we return to below.

Figure 1.1 North–South divisions according to the Brandt Line.

Source: Adapted from Brandt Commission, 1980.

One of our reasons for producing this book was that our own experiences of living and working in the Global South (see Case Studies 1.1, 1.2 and 1.3) don’t fit easily or comfortably fit within this academic framework. We all see ourselves as geographers, rather than ‘development experts’, and, in thinking about our various research topics in Mexico, South Africa, India and elsewhere, we’ve drawn directly on debates ranging across the social sciences, and not from development theory alone. Even though our own work addresses social, economic and political concerns, we’re each acutely aware that there’s a lot more to life in the South than a list of problems – and one of our motivations for writing is to communicate something of the richness of its places and peoples, something that often gets squeezed out of many undergraduate courses.

As geographers we approach an examination of the people and places of the Global South drawing on specific geographical concepts, particularly space and place (see Key Concepts 1.1 and 1.2). We are interested in understanding spatial patterns at a range of scales, but also how different spaces are connected through networks and flows of people, ideas and things. A recognition of how meanings are attached to particular places and how peoples and places are represented will also be highlighted as one of the themes of the book. This is discussed further later in this chapter and in Chapter 2. Geography as a discipline spans the study of both the human and physical environments and interactions between them. However, this is not a textbook that attempts to engage with the physical geography of the Global South. The natural environments of the South do, nonetheless, make their presence felt at various points within the book – in dominant representations of the Global South (Chapter 2), as issues for international governance (Chapter 3), as material contexts of people’s lives (Chapter 8) and elsewhere.

In this book, our working definition of the Global South stays with the problematic division put forward by Brandt, but we use this deliberately to highlight the diversity that exists south of the Brandt Line rather than trying to present a singular view of the experiences of its countries, regions and peoples. Within the Global South today are emerging superpowers and failed states, the world’s fastest-growing economies and the vast majority of the global poor: a dynamism and diversity captured within the United Nations Development Programme’s 2013 Human Development Report, itself titled The Rise of the South (UNDP, 2013). While being subject to European, Japanese or American colonialism might have been an important part of the history of many Southern countries, it has not been the experience of all (Ethiopia and Thailand, for example, had only the briefest of foreign occupations). The Global South contains massive variations in environmental conditions, cultural values and practices, political and economic systems, and ways of life that we can only begin to sketch out here. What does link the regions of our definition, however, is that these are the parts of the world that have been commonly described for many decades now as developing areas. Our book puts the spotlight on these places both to give them more attention than they normally receive from ‘mainstream’ social science in the Global North and to challenge standard ways in which they are represented.

CASE STUDY 1.1

Glyn’s story: arriving in Kolkata

My own understanding of the Global South has been closely shaped by my experiences of living and working in India, and one underlying question guiding my research has been what does ‘democracy’ mean for people’s everyday lives today. Kolkata has a special place within that experience: it was where I learned Bengali before starting my doctoral research, and it was also the first ‘proper’ city I had ever lived in.

First arriving there in 1992, my mental image of the city was informed by media stereotypes (of Mother Teresa and the ‘City of Joy’) and the little I knew of its recent history: Kolkata absorbed two tidal waves of crisis immigration (in 1947, and then during Bangladesh’s independence struggle in the early 1970s), it was a declining industrial centre, and had a reputation for radical and often violent politics. Did I find a city engulfed by overcrowding, poverty and political activism? Before even stepping off the train, there was plenty of evidence of all three: a million passengers pass through Howrah station every day, there were plenty of people sleeping rough on its platforms, and rival political parties competed to unionize its porters. But these images were quickly overtaken by others: the spontaneous games of street cricket during every strike or public holiday, the city’s pride in its annual book fair, and its passion for adda – a form of free-flowing intellectual and political debate, fuelled by endless cups of sweet tea. This was a city where dollars and Coca-Cola were still traded on the black market (India’s economic ‘liberalization’ was just beginning in the early 1990s), but also one that possessed a self-assurance and cosmopolitanism all of its own.

Kolkata today is a city that is changing fast, with its older neighbourhoods (Plate 1.1) being overtaken by frenetic construction. High-rise apartment blocks are emerging from former paddy fields at the city’s edge, along with new air-conditioned shopping malls in its southern suburbs (they now do sell Coke, alongside far more luxurious Indian and foreign goods). The billboards – no longer hand-painted – advertise up-market property developments and IT career opportunities to its growing middle classes. But alongside these signs of affluence, even within some of the city’s richest neighbourhoods, you still find people plying hand-pulled rickshaws and living in squatter settlements. As a friend explained to me: ‘Kolkatans, unlike Delhi-ites, have never forgotten that we live in the developing world. The poor live among us: they are a vital part of this city.’

Plate 1.1 A middle-class neighbourhood in southern Kolkata, India.

Credit: Glyn Williams.

CASE STUDY 1.2

Katie’s story: researching gender in Oaxaca City, Mexico

I first went to Mexico in 1990 as a Master’s student for a 3-month fieldwork visit researching women’s work in a low-income informal settlement o...