![]()

Part I

The Course of Events

![]()

1

British North America in 1763

The Colonies and Their People

In February 1763 the major European powers, including France and Britain, agreed on a peace treaty at Paris that brought an end to the Seven Years’ War. That conflict, known in Britain’s North American colonies as the French and Indian War, was the culmination of a prolonged struggle for imperial mastery between France and Britain that persisted throughout the eighteenth century. In its North American dimension, France had initially enjoyed success during the war, inflicting a series of humiliating defeats on British and colonial forces with the help of its Indian allies. Eventually the British recovered, capturing Quebec in 1759 and Montreal in 1760, as well as a number of French possessions in the West Indies. Under the terms of the Treaty of Paris, France ceded to Britain all of her territory in North America east of the Mississippi River (with the exception of New Orleans). In return, France retained fishing rights on the Newfoundland Banks, as well as the small North Atlantic islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon. In addition, Britain returned captured French colonies in the West Indies, including Martinique and Guadeloupe. Spain, which fought unsuccessfully as an ally of France, ceded Florida to Britain but was compensated by France with all French territory west of the Mississippi and New Orleans. The geopolitical results of this diplomatic settlement were profound. After more than 150 years, France had been removed from North America and Britain was nominally the master of all the vast territory of eastern North America, from the Atlantic west to the Mississippi and from Hudson Bay in the north to the Florida Everglades in the south. Winning this territory at the negotiating table would prove less difficult than governing it.

With the defeat of France, the unchecked growth of the British North American colonies seemed a real possibility. In the wake of the Peace of Paris and the Proclamation Act, Great Britain had twenty-six colonies in the New World, including seventeen in North America.1 Despite the number of colonies, the population of British North America was concentrated in the thirteen seaboard colonies that would declare their independence from Britain in 1776, especially in the coastal region running from Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in the north to Savannah, Georgia, in the south. In these colonies, the population was growing at a remarkable rate, which not only threatened the Indians of the West but also unnerved imperial officials in London.

The population of the thirteen British colonies that became the United States grew at a prodigious rate during the eighteenth century. The population doubled nearly every generation (see Table 1.1). Thus, when Benjamin Franklin was born in 1706, the population was approximately 300,000; when he died in 1790, the American population was nearly four million people. By 1800 the population of the United States exceeded five million souls. It is likely that Britain’s American colonies had one of the fastest-growing populations on earth during the eighteenth century. Indeed between 1763, when the Anglo-American dispute commenced, and 1815, when it was finally resolved, the American population increased from more than 1.5 million to more than 8.4 million people. During the eighteenth century, population growth was seen as a measure of power. Consequently, many commentators in America and Britain welcomed this growth as an indicator of future American and British greatness. Some British observers were wary of American growth, however, fearing it might lead to a desire for autonomy and possibly independence in the colonies.2

Although the British American population was concentrated along the eastern seaboard, it was not evenly distributed. In 1770, on the eve of the Revolution, the New England colonies (Massachusetts—including what is today the state of Maine—New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Connecticut) had a population of 581,038, which was 27 percent of the colonial population. The Middle Colonies (New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware) had 555,904 residents, which constituted 25.9 percent of the total population. It follows that slightly less than half (47.1 percent) of the American colonists lived in the South (Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia). With its longer growing season and fertile soil, the South was attractive to migrants from other colonies as well as Europe. As the region where slave-based agriculture had proven profitable, the Southern colonies were the destination for most enslaved Africans brought unwillingly to America during the century. These factors, combined with the very high American birth rate, gave the South as a region, the largest percentage of the colonial American population. The Southern population was divided between the older, more populous colonies along Chesapeake Bay, Virginia, and Maryland, which had 649,615 residents in 1770, and the newer, less populous colonies of the Lower South—North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia, which had a combined population of 344,819 on the eve of the Revolution.3

Table 1.1 British American population growth, 1700–1800 | Year | Population |

1700 | 250,888 |

1710 | 331,711 |

1720 | 466,185 |

1730 | 629,445 |

1740 | 905,563 |

1750 | 1,107,676 |

1760 | 1,593,625 |

1770 | 2,148,076 |

1780 | 2,780,368 |

1790 | 3,929,625 |

1800 | 5,297,000 |

British American population growth during the eighteenth century was the result of two important factors: natural increase and immigration. The overwhelming majority of eighteenth-century colonial Americans lived in households that were dependent upon agriculture. American society was characterized by relatively large amounts of land and a shortage of labor. Since the family was the essential economic as well as social unit, large families were a valuable source of labor. Thus, economic necessity combined with demographic factors—an increase in life expectancy during the eighteenth century by comparison with the seventeenth century, as well as early marriage—to produce a high birth rate. The average American woman during the eighteenth century could expect to marry in her late teens or early twenties (the average age of marriage for men was slightly higher). She could expect to become pregnant quickly and was likely to repeat the cycle of pregnancy, birth, and lactation every two years for the duration of her childbearing years. For most eighteenth-century American women, maternity, with its attendant risks, was a fact of life for the first two decades of married life. The result was a rapidly growing population, with families averaging six to eight children, as well as a definition of womanhood that was indistinguishable from motherhood.4

The American population swelled not only through an increase in the birth rate but also as a result of a large influx of immigrants during the eighteenth century. All told, nearly 600,000 immigrants from Europe and Africa, voluntary and involuntary, migrated to British North America between 1700 and the Revolution.5 The rate of immigration increased as the century progressed. In the fifteen years between 1760 (when fighting between the British and French effectively ended in North America) and the outbreak of the War of Independence in 1775, more than 220,000 immigrants arrived in America, at a rate of approximately 15,000 per annum. As a result of this influx, almost 10 percent of American colonists were foreign born when the War of Independence began.6 Eighteenth-century immigrants had a profound impact on the development of pre-revolutionary America. They came from two places: Europe (including the British Isles) and Africa.

More than 300,000 Europeans migrated to British North America between 1700 and 1775. Unlike their predecessors, who settled the colonies during the seventeenth century and were mostly of English origin, the immigrants of the eighteenth century were remarkable for their heterogeneity. Indeed, the 44,100 English men and women who migrated during the eighteenth century made up only about 14 percent of the migrants.7 The remaining European immigrants were drawn from throughout northwestern Europe and the British Isles. However, the two largest immigrant groups were German speakers from central Europe and the Scots-Irish. About 85,000 Germans, many from small radical Protestant sects, were attracted by the religious toleration and fertile soil of Pennsylvania. Most of the German migrants came in family groups, and approximately one-third of the migrants came as redemptioners, or contract workers, who pledged their labor (or that of their children) to pay for their trans-Atlantic passage. Philadelphia was the first destination for many of these migrants, who established numerous German-speaking settlements in eastern and central Pennsylvania. Within Pennsylvania, where the German population was concentrated, the immigrants maintained an important degree of religious and cultural autonomy and exercised considerable political power and sustained a German-language press until after the Revolution. By the eve of the Revolution there were also congregations of German pietist immigrants in North Carolina, Maryland, New Jersey, and New York, as well as Pennsylvania.8

The other major group of European emigrants to America before the Revolution was the Scots-Irish, Protestants from Ulster. Estimates vary widely as to how many Scots-Irish migrated, but it is likely that the figure is around 200,000.9 These migrants, mostly descended from Scottish Presbyterians who emigrated to Ulster in the seventeenth century, resented discrimination at the hands of the English, who gave primacy to wealthier Ulster Episcopalians. Many were hard-pressed tenant farmers, who were attracted to America as much by the promise of cheap land as religious toleration. They, like the Germans, arrived in Philadelphia as their first port of call. Most then migrated to western Pennsylvania and then up and down the Appalachian region. By the eve of the Revolution, Scots-Irish settlers not only predominated in western Pennsylvania but also in the frontier regions of Virginia and the Carolinas. Just as their forebears found themselves guarding the frontier between the English and Catholic Irish in Ulster, the Scots-Irish in America found themselves along another frontier between the coastal settlements and territory occupied by Native Americans. The Paxton Boys gave expression to the difficulties faced by the settlers, who felt threatened by the Indians and ignored by political authorities along the coast.

The arrival of vast numbers of Scots-Irish and German immigrants, as well as lesser but still significant numbers of Irish, Scottish, Welsh, and other European immigrants, made the European population of America much more ethnically diverse than it had been in 1700. No longer could it be assumed that all white Americans were of English descent. Thus, during the revolutionary period, Pennsylvania was a complex ethnic mosaic with a white population that was only 19.5 percent English, 33.3 percent German, and 42.8 percent Celtic (Scots-Irish, Irish, Scottish, and Welsh) in origin. Similarly in South Carolina, only about a third of the white population was of English extraction. Such diversity was not uniform. The white population of New England was 75 percent English. Nonetheless, in the remainder of the colonies, the majority of the population was not of English extraction. When the revolutionary crisis erupted, the English officials and English-dominated Parliament that ran the British Empire could not assume that cultural affinity between the colonists and their rulers would promote unity.10

The Enslaved

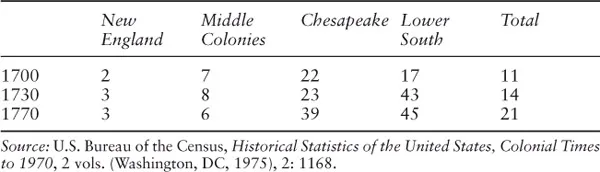

The largest group of migrants to eighteenth-century British North America was enslaved Africans. Although the first enslaved Africans arrived in British America in 1619, chattel slavery evolved slowly during the seventeenth century. During the eighteenth century, importation of black slaves from the West Indies and directly from Africa increased as planters sought a cheap alternative to indentured servants as a source of labor. As a result, nearly 280,000 Africans were forcibly transported to North America to endure the rigors of perpetual racial servitude. As a consequence of colonial imports of slaves, the number of people in North America who were either African born or of African descent increased steadily throughout the eighteenth century (see Table 1.2). Indeed, by the beginning of the American Revolution approximately one in five Americans was black. The enslaved population was not evenly distributed throughout the colonies. While, broadly speaking, there were few slaves in the northern colonies and quite a large proportion in the southern colonies, there were wide variations within the regions and even within individual colonies. For example, although New England had an enslaved population of only 3 percent at the time of the Revolution, 6 percent of Rhode Islanders were slaves of African origin. Similarly, the Middle Colonies taken as a region had an enslaved population of 6 percent on the eve of the Revolution, yet New York’s slave population was 12 percent. Most enslaved persons were concentrated in the southern colonies, yet even among the settlements where the practice of slavery on a large scale was economically viable there were important regional variations. Thirty-one percent of the Marylanders, for example, were enslaved in 1770 compared to 61 percent of South Carolinians. (South Carolina was the only mainland British colony with a population of which the majority was enslaved.) Within colonies themselves, there was an uneven distribution of slaves.11 Most enslaved Rhode Islanders were concentrated around Narragansett Bay, and New York’s slaves largely lived and worked in New York City and its environs. Within the South similar concentrations occurred, although on a much larger scale. In the Chesapeake colonies of Virginia and Maryland, most of the enslaved population was concentrated in coastal tidewaters where tobacco cultivation was centered. South Carolina’s black majority largely resided in the coastal lowlands of the colony. Across the South there were relatively few slaves in the frontier regions.

The experiences of enslaved people varied widely by region and over time. Northern slaves, few in number, were concentrated in the maritime trades and were also employed as manual workers in cities and towns. Wealthy urban merchants kept some as personal servants as a mark of status. The few enslaved persons in the rural north usually worked as farm laborers in close contact with their white masters, in isolation from other slaves. In the southern colonies there was a comparable diversity of experience. Slaves in Maryland and Virginia were generally scattered on hundreds of small farms and plantations given over to tobacco and cereal production. Most slaves in the region toiled as agricultural workers performing a variety of tasks, although on the larger plantations numbers were concentrated enough to allow for a degree of specialization and the employment of some slaves as personal servants. In South Carolina slaves enjoyed a degree of autonomy under the task system, but were confronted by an unhealthy climate and difficult conditions cultivating rice and indigo.

Table 1.2 Africans as percentage of population

Regardless of where they lived or the labor they performed, the overwhelming majority of African Americans (with the exception of a small number of free blacks in the northern colonies) shared a common status as chattel slaves. As a result, they were, in the eyes of the law as well as custom, property to be bought, sold, punished, and forced to labor without pay in perpetuity. Slaves were not the only unfree migrants to eighteenth-century America. Tens of thousands of German redemptioners, indentured servants, and convicts found their way to the colonies. Indeed, unfree migrants constituted the majority of the immigrants to eighteenth-century America. Slaves were set apart, however, by their race and the permanence of their status. Other unfree migrants could aspire to freedom, economic, social, and political, which was denied to African slaves. Their status as slaves, moreover, would be transmitted to their children. As a result, slavery as practiced in eighteenth-century America rendered one-fifth of the population, identifiable by race, as a permanent class of unfree laborers. The presence of slave labor on such a wide scale had profound implications for American society during the era of the Revolution. When colonists of European origin protested the existence of a British conspiracy to enslave them, they did so with a clear and intimate knowledge of what slavery was. In practical terms, many of the men who would lead in the revolutionary struggle—most notably figures like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson—relied on slave labor to provide them with the status, time, and wealth that made them effective leaders. Ultimately, slavery was a constant presence upon which the American struggle for independence rested. Its presence challenged the fundamental premises of the Revolution.12...