- 348 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

What is Scenography?

About this book

The third edition of Pamela Howard's What is Scenography? expands on the author's holistic analysis of scenography as comprising space, text, research, art, performers, directors and spectators, to examine the changing nature of scenography in the twenty-first century.

The book includes new investigations of recent production projects from Howard's celebrated career, including Carmen and Charlotte: A Tri-Coloured Play with Music, full-colour illustrations of her recent work and updated commentary from a wide spectrum of contemporary theatre makers.

This book is suitable for students in Scenography and Theatre Design courses, along with theatre professionals.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

‘Don’t throw the baby out with the bath water!’

(German proverb attributed to Thomas Murner, 1512)

SPACE

MEASURE TO MEASURE: PLAYING IN THE SPACE

Theatre takes place wherever there is a meeting point between actors and a potential audience. And it is in the measured space of that meeting and in the generation of that interaction where the scenographer sets his or her art. Space lies silent, empty and inert, waiting for release into the life of drama. In whatever size, shape and proportion, space has to be conquered, harnessed and changed by its animateurs before it becomes what Ming Cho Lee has called ‘an arena where the great issues – of values, of ethics, of courage, of integrity and of humanism are encountered and wrestled with’ (Ming Cho Lee in a forum at Barnard College, Columbia University in 2001; see also Ming Cho Lee, ‘The Akalaitis Affair’ American Journal, 10.5, May/June 1993, p. 4).

The world view of scenography reveals that space is the first and most important challenge for a scenographer. Space is part of the scenographic vocabulary. We talk about translating and adapting space; creating suggestive space and linking space with dramatic time. We think of space in action, how we can make it and break it, what we need to create the right space, and how it can be constructed with form and colour to enhance the human being and the text. Some play games with space, searching for its metaphor and meaning in the quest to define dramatic space. There is a complex alchemy between spaces and productions that provokes the creators to tame an unknown space into a space that eventually will fit the production like a glove.

Space is described by its dynamics – the geometry, and its characteristics – the atmosphere. Geometry is a way of measuring space and describing it so that someone else can visualize it. Understanding the dynamic of the space means recognizing, through observing its geometry, where its power lies – in its height, length, width, depth or the horizontal and vertical diagonals. Every space has a line of power, reaching from the acting area to the spectator, that the scenographer has to reveal and explore. This line of power is actively felt by performers on the stage, as they look into the auditorium and assess where they feel most strongly placed. A production can be planned to exploit and capitalize on these strengths, so that the actors can be seen and heard to their best advantage. The characteristic of a space also has to be taken into consideration from the first moment of planning. Its atmosphere and quality deeply affect both audience and performers. A space is a living personality with a past, present and future. Brick, ironwork, concrete, wooden beams and structures, red seats and gilt and decorated balconies all give a building its individual characteristic. Observed space has to be recorded, through accurate ground plans and elevations, photographs and on-site drawings, so that it can be recreated in the studio as a coloured and textured scale maquette. It should always include at least the first rows of seating, and have fixed points of view from all the extreme positions of the house. The empty maquette which exposes the bare bones of the space is so important because it is the first means of direct communication between director and scenographer as they start to work together. The lighting designer and the movement director can also see the possibilities of their contribution through the completed maquette. The creation of carefully made scale figures adds the human dynamic to the empty space (it helps if they do not fall over, and they often do), for the use and manipulation of scale on the stage is a scenographic art that stretches space from the maximum to the minimum to give it meaning. These ideas can be tried out in the maquette and games can be played with the space by enlarging or reducing the size of a wall or door, or simply the furniture, or creating a deceptive space that alters the proportion of the human figure. Through this process the dynamic that the space provides can be moulded and sculpted until it starts to speak of the envisaged production.

Scenography and architecture are very closely linked, and many architects have brought their understanding of space to the theatre. Adolphe Appia (1862–1928) was the first stage architect of the twentieth century, and introduced an architectural openness and freshness to his theatre spaces at a time when illusionistic painted scenery filling the stage was the standard arrangement. In 1911, in Hellerau in Germany, he created his Rhythmic Space – an arrangement of steps and platforms providing changeable modules of verticals and horizontals. Working on these different levels enabled actors to be isolated in specifically focused shafts of light, enhancing their presence on the stage in space without extra scenery, and began a quest for more sculptural scenic solutions. Architects are often visionaries and innovators, encompassing philosophy, art, music and politics, plus an understanding of materials and the ability to dream out loud. Erich Mendelsohn (1887–1953) was born in East Prussia, and buildings in Germany, England, America and Israel testify to his vivid imagination. From 1912 to 1914 he designed settings and costumes for pageants and festive processions, part of the German expressionist movement. He remade the interior of the Deutsches Theater, but considered he had made a wise career choice when he chose Architecture as his medium. His inspiration came from observing nature and landscapes while listening to music by Bach and dreaming about creating buildings that expressed the moment of the time, using all newly developed technology and materials. He drew free sketches from his imagination on concert programmes and scraps of paper and captured the spontaneous ideas of these quick and fluid sketches, transforming them through models into concrete buildings. These soaring visions of buildings expressed hope and optimism in the dark days of world wars, and his own personal faith in the future. Like scenographers, Mendelsohn always started by being excited by the challenges and possibilities of responding to a space, describing his process as: ‘I see the building site, the plane, the space […] and I excitedly take possession of it’ (Dynamics and Function, Stuttgart: IFA, 1999, p. xii).

His search to combine dynamics and function, and his profound love and inspiration from the harmonies and counterpoint mathematics of Bach’s music, are evident in the early expressionist buildings. Using materials of the day, he created external structures that housed the working and corporate sectors within one dramatic volume. He created a spatial relationship between the performer/factory worker and the audience/client that had the same intensity as the integrated audiences and performers of the old baroque theatres of the early eighteenth century. These theatre buildings had internal wooden interiors, compact and organized. They conceived a whole oval space of stage and auditorium as one entity in which the performers played for the spectators that they could see and not at spectators that were sensed but not seen sitting in the dark.

The baroque theatres of Europe were largely constructed on an axis leading from the centre of the performing area in a diagonal upwards to the centre of the Royal box placed in the first circle of the horseshoe-shaped auditorium. A proscenium frame holding the front curtain marked the division of the space, but a forestage protruded into the audience, where allegorical characters could address the Royal box directly, in front of the curtain, and also be seen from all parts of the house. The orchestra, essential to all performances, was placed on the same level as the spectators. The spectacular event was the raising of the curtain, usually after a musical and spoken prologue. The stage space revealed elaborate totally symmetrical scenic arrangements of borders and flats painted in detailed perspectives that were perfect from the centre of the Royal box, and less and less perfect from the seats on either side. Once the curtain had been raised, the stage space was enhanced by candles and footlights, all focused towards the prime central position on the stage. The curtain was never lowered during these performances until the end. Elaborate scene changes and transformations took place in full view of the spectators, and were as much part of the performance as the masque or opera being performed. These transformations exploited to the maximum all the planes of the stage space, using the vertical height from above to indicate divine space, and the depth below the stage floor as the demonic space. Stage traps and winching devices could make performers and scenic effects rise from below and descend from on high, while each side of the stage held hidden spaces at least as wide as half of the visible stage, enabling perspectives of cities, landscapes, and buildings to slide on and off in parallel motion. Armies of unseen sceneshifters operated the heavy wooden machinery underneath, above, and in the side wings of the stage. Many were unemployed boatbuilders and naval workers from Venice and Genoa who brought their construction skills and techniques into the underworld of the baroque stages. Every inch of the theatre space was exploited to the maximum, and, like warships, these theatres were working machines. Their legacy remains in the many technical words that connect boats with theatres such as ‘rigging’, ‘splicing’, ‘deck’, ‘shackle’, ‘winch’, ‘pulley’, etc.

There are many examples of baroque theatres still in existence in Sweden, France, Italy and the Czech Republic, with all the machinery still in working order. The beautiful Estates theatre in Prague, where Mozart’s Don Giovanni was first performed, is typical. Exquisite, elegant and seductive, with a strong intimacy created by the raked stage thrusting performers into the oval auditorium, its original purpose was as much to be seen in as to see. In fact only one-third of the spectators can see the stage, and they have to be seated in the central body of the oval; two-thirds, seated in galleries and boxes that get less comfortable as they get higher, only get a sideways view of the stage. Mirrors on the sides of the boxes help to reflect what is happening on the stage, although the spectator has to turn away from the stage and towards the other spectators to see in them. The higher up the seat, the less is visible to the back of the stage. Any scenery placed beyond the halfway point of the stage is likely to be seen only by those sitting directly in front. In this elegant and beautifully proportioned theatre the seating of the spectators reflects exactly the tradition and class structure of the society it represented. The baroque theatre space continued well into the mid-nineteenth century, developing into the ornate gilt auditoria of the grand opera houses – built on similar principles, but much bigger to house the operas that had become part of national repertoires all over the world. By this time the enlarged orchestras had acquired conductors, housed in orchestra pits sunk between the audience and the performers. Although the architectural space had increased, the actual practical playing space on the stage was reduced as performers were obliged to sing arias as far down front as possible so they could both see the conductor and be heard. Composers wrote for large choruses that could make a musical and acoustic wall backing the singers. The symmetrical scenery of the baroque theatre gave way to illusionistic painted cloths that were only partially seen in the cavernous stage spaces when lit by limelight, gas and finally electricity.

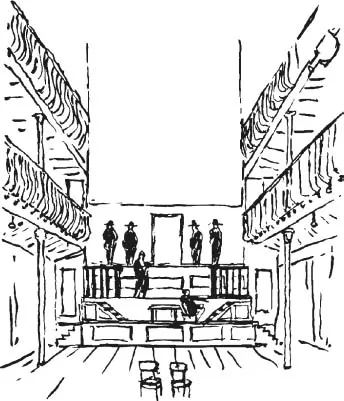

The beginning of the twentieth century reveals a multiplicity of competing theatre ideals, then as now searching for the elusive definition of the ideal theatre space. As the grand opera houses continued to attract one section of the population, smaller and more intimate popular music halls created their own versions. One such is the Hoxton Music Hall, a small nineteenth-century theatre space in a dark part of London (Figure 1.1). It was formerly a local venue for popular singers, and fronts onto a busy rundown shopping street. It is a high, narrow, rectangular building with three galleries wrapped around a small stage at the far end of the rectangle, giving the effect of a version of an Elizabethan courtyard theatre or a seventeenth-century Spanish ‘corral’ theatre. Although it has a faded and nostalgic charm, it has nothing to offer scenographically except itself. Assessing the dynamic of this space, and its line of power, it is the vertical height held between the galleries, and the small stage built on three levels with entrances at each level, that is the dimension to be exploited. Its characteristic is a long, narrow interior emphasized by a row of thin iron pillars with gold capitals on either side supporting ornate ironwork balconies painted red and gold that run the circumference of the space. Like many halls of its period it would have been constructed by local builders, probably by eye, for it is distinctly uneven and made out of rough, cheap, heavy wood that has now been painted dark grey.

1.1 Drawing of Hoxton Hall, London

The three-level stage with small steps and balustrades leading from one level to another is a scaled down, and perhaps unknowing version of Adolphe Appia’s ‘rhythmic space’. When a production is created there that responds to the space, using actors and movement, simple furniture and props and imaginative staging, a real dialogue with the audience begins.

The intimacy of this space inevitably emphasizes the performer and the spatial placing of the action in the stage space. Space for the scenographer is about creating internal dramatic space as well as responding to the external architectural space. To be able to create potent stage images that describe the dramatic space starts with understanding and responding to the texts that are to be played. Throughout the twentieth century, starting with Strindberg’s intimate theatre in 1906, there has been a continuing movement and search for spaces and forms to house chamber plays and smaller-scale plays that provide an alternative to the grand and expensive spectacle theatre. A neutral space, sometimes a black box, has developed as a self-contained dramatic space that can be used equally effectively in traditional proscenium theatres and more modern theatre buildings. If these neutral spaces have invisible technical facilities able to shape and reshape the internal volume of the space to suit the scene, a plain black box becomes a truly expressive space. The emphasis is then focused on the dramatic space created between the performers and the object, and on the furniture or scenery needed to tell the story. The stage floor becomes the most important visual focus, especially if the auditorium is raised and the spectators are looking down onto the stage. When the stage floor is raked or angled to counterbalance the rising height of the auditorium, the actor’s eye level meets the audience intimately, directly and powerfully, and a strong connection is immediately struck, just as one can feel when standing on the empty stages of the old baroque theatres.

By the middle of the century small multipurpose polyvalent studio spaces had become part of most theatre buildings. With shrinking arts budgets worldwide, these small studio theatres, conceived originally as a home for new plays, or cheap productions (unfortunately put into the same bracket), have now become the favourite places for making new and vibrant production...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- World View

- Preface to the Third Revised and Expanded Edition

- Introduction

- Part 1 Elements of Scenography

- Part 2 investigations

- Afterword

- Postscript

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access What is Scenography? by Pamela Howard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Theatre. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.