![]()

Chapter 1

From Folk to a Folk Race

Carl Arbo and National Romantic Anthropology in Norway

Patricia G. Berman

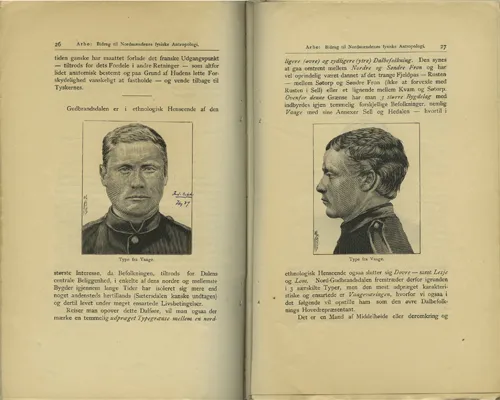

It is axiomatic that the history of race as a concept is entangled with the history of photography as a medium, that photography helped to make racial taxonomy seem tangible and believable through “reliable” evidence. Photography became a crucial evidentiary tool in the fields of ethnology and anthropology as soon as the medium was brought into the world through its seemingly transparent registration of physical fact. In Norway, race as a scientific concept, and photography as a medium, became entangled with nation building as a process in the work of military physician Carl Oscar Eugen Arbo. From the 1870s to just after the turn of the century, Arbo documented 20,000 people, gathering anthropometric data in Norway’s eastern and southern regions.1 Military recruits were his primary subjects. In compiling their measurements and interpreting their characters, Arbo “demonstrated” distinctive racial typologies within different regions of Norway based on hair and eye color, body dimensions, and especially cranial configuration. By photographing the recruits, he made his statistics legible as embodied subjects, as superior blonde “long skulled” or the lesser dark, “round skulled” races (Figure 1.1). In addition to his publications, he lectured at professional meetings in Norway and throughout Europe, illustrating his talks with lantern slides of the photographs taken of the recruits. In the 1880s and 1890s, Arbo published Contributions to the Physical Anthropology of the Norwegians, a series of regional surveys that established him as the leading pioneer of anthropological research and garnered him national and international recognition and awards.2 Arbo’s data collection recast the imagined identity of Norwegians from a “folk”—the most potent unifying idea within Norway’s nation building efforts—to a “folk-race,” deploying photographs in the service of indexing a population into a racial hierarchy. In a procedure that Daniel Segal terms “the co-occurring en-racing of status and framing of races,”3 Arbo’s photographs validated, as scientific instruments, the exceptionalist rhetoric of national romanticism and contributed to the scientific fiction of a Nordic/Germanic “master race.”4

Figure 1.1 Carl O. Arbo, Vågå Type, xylograph, Fortsatte bidrag til Nordmændenes fysiske antropologi: Østerdalen og Gudbrandsdalen (Kristiania: Kommission hos Th. Steens Forlagexpedition, 1891), 26–27, Harvard College Library. Photographer: Farimah Eshraghi, Wellesley College.

The repercussions of Arbo’s photographic work extended far beyond the borders of Norway and deep into the twentieth century, making the photographs important artifacts in the history of race and racism. His work served as the basis for later anthropometric surveys that converged with the eugenics movement at home and internationally, contributing to the myth of a “pure” Nordic race, a concept freighted with inexpressible historical and contemporary destructiveness. This article looks at the role of Arbo’s photographs in promulgating his work, their bases in physical anthropology research, and their scientification of the scholarly and visual rhetoric of Norway’s nation building efforts of the nineteenth century.

Arbo’s Physical Anthropology

Carl O. Arbo served as a military physician from his medical education in the 1860s until his retirement in 1902. In 1875, he published his first significant study, in which he suggested that the medical examination of military conscripts might also offer data for statistical, ethnographic, and anthropological research. His initial aim, following similar military data collections in France, Austria, and Germany, was to measure the physical capacity of the Norwegian (male) population, and thus to gauge the strength and fitness of the nation.5 The military conscription system, having been initiated only a decade and a half earlier, created a male population from around the country that was homogenous in age, enabling a built-in sample set.6 In taking measurements of those young men—arm length, height, etc.—he noted variations in morphology among those born in the different valleys in southern Norway and those from coastal areas, observations that led to his interest in physical anthropology.7 Traveling throughout southern Norway, he increasingly became committed to the theory that observed regional variations in physical strength among the recruits were explained by racial difference (understood to be a constant) rather than by environmental or economic considerations (understood to be fluctuating).8 He did not travel to northern Norway, instead contracting with others to carry out the work on a population that included a large number of Sámi people (the endonym for the historical derogatory term “Lapp”) and Kvens (people from area of the Gulf of Bothnia who moved to northern Norway) who had been stigmatized throughout the nineteenth century as a “people apart” from the Norwegian “folk.”9

The decades in which Arbo conducted his work were also the period of the professionalization of the medical and hygiene fields.10 As elsewhere in Europe, a concern with degeneration—the effects of illness, alcoholism, and mental health—had given impetus to the study of decreasing vitality among children, and therefore the future prospects of the nation.11 Concerns about illness and reproductive capacity within the population were amplified by the mass emigration of Norwegians to the United States, a demographic crisis in which approximately 1 percent of Norway´s population emigrated each year beginning in 1825, rising to 1.5 percent in 1882.12 Between 1836 and 1865, 76,674 people emigrated from Norway. In the same years, some 30,000 people entered the country, such that for every 100 who emigrated, forty immigrated, with the popular notion that the best were leaving, replaced by a lesser population.13 In 1851, the Norwegian constitution of 1814, which had prohibited Jews, Jesuits, and monastic orders from immigrating, was amended to offer religious freedom.14 Paragraph Two of the constitution—known as the “Jewish Clause”—had manifestly been drafted to protect the Lutheran State Church, but magnified a deeper history of xenophobia and anti-Semitism. A decade-long moral campaign waged by the poet Henrik Wergelend led to the reversal of the discriminat ory paragraph.15 Although the country remained homogenous relative to other European nations, groups outside of so-called “Norwegian ethnicity”—Sámi, Finns, Roma, Romany (“travelers”), and, by 1865, twenty-five Jews16 —were marginalized. There were also political concerns with the border between Norway and Russia following Russia’s wars and annexation of Sweden and Finland, from which a population of Finns had resettled in Norway and across which Sámi communities could travel, holding the potential to be “fifth column” Russians.17 As noted by historian Øystein Sørensen, the distinction between “us” and “them” was greatly amplified during this period.

Arbo sought some of the most advanced training in physical anthropology in Europe, which he synthesized and implemented in Norway. He subscribed to the theory of polygenism— that humans can be divided into separate and immutable species—and that variations in type are due to racial mixing with detrimental results.18 Located in Stockholm with the Norwegian Royal Guards in the early 1870s, Arbo made contact with the group of Swedish anthropologists who continued the research of Anders Retzius, anthropologist and Professor of Anatomy at the Karolinska Institute. Around 1840, Retzius had proposed a method of racial classification through craniometric analysis—length-to-breadth ratios—identifying dolichocephalic (long skulled) and brachycephalic (short skulled) human “types.” Combining these two categories with other considerations, Retzius had organized populations into distinctive races that he ranked in terms of superiority with the dolichocephalic types, or Germanics, at the top of the hierarchy.19 According to Retzius, the populations of central Sweden were “long skulls” and the Sámi, “short skulls.” The ratios that he developed formed a classification system that was used as a criterion for racial research for the next decades.20 According to Retzius, it was a “universally acknowledged fact” that Celtic and Germanic peoples were intellectually superior due to their possession of a narrow, long skull and a protruding occipital lobe, in contrast to the “inferior” Slavs and Sámi with their broad skulls and supposed small occipital lobes.21

Retzius had built his system in part on the findings of German anatomist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, who in 1775 had published De generis humani varietate native, in which he fashioned five human races based on skin color and other markers of what he saw as essential differences, including cranial configuration. Working in analogy to the Swede Carl Linnaeus’s botanical system, Blumenbach assembled an international skull collection as the basis for his human racial taxonomy. He supported the theory that all humans had emerged from one species and had become differentiated through adaptation to their local environments and determined that a female cranium from the Caucasus was the most “beautiful.” So perfectly had the species adapted to the Caucasus region that he identified the “Caucasian” as a superior type of human. The configuration of that skull, and the racial markers that accompanied it, became his index. The other so-called races or varieties—the American, Mongolian (“almost square”), Malayan, and Ethiopian—had emerged through adaptation to less hospitable environments.22 Nancy Leys Stepan has argued that the strategy of analogy employed by Blumenbach is a type of a false narrative that, through repetition, becomes dogma, such that “enlightened” and “lower races” were uncritically embedded in the European scientific community.23 Analogical thought, and such a designation as “beautiful,” are exercises in taste, of aesthetics and connoisseurship, that Margaret Olin reminds us were entangled intimately with the discipline of anth...